Strands: Hotere / Reihana / Brickell (2025)

Closes

Jan 25, 2026Posted on

Nov 21, 2025Event type:

Art , Exhibition , Public Art , Public Program ,Price:

FreeVenue:

Milford GalleriesAddress:

18 Dowling Street, DunedinRegion:

Dunedin , National , Online , Otago ,

Ambiguous states of being and mutable identity, where the past, present and future sit together while being interrogated, are but some of the ‘strands’ interconnecting the works of Ralph Hotere, Lisa Reihana and Heidi Brickell.

Hotere entwined the symbolic presence of Catholicism with the Māori spiritual world. In his wonderfully indeterminate black space, at once elemental and mystical, he united the metaphorical and the metaphysical. His parabolic language – dark to light and vice versa – built narratives of the human condition, nature itself, Te Aupouri tribal belief and Catholic theology. Believing art to have a fundamental political and social purpose as its reason for being; in important works such as Winter Solstice (1988) and Fernando Pereira (2005) he built explicit requiems about the sinking of the Rainbow Warrior by the French on 10 July 1985. In the iconic stained-glass work Winter Solstice (1988) that hung in his Observation Point studio, a tau cross becomes Christ’s body, with rainbow-shaped bleeds falling from the spear wounds. In the latter arched window frame work, he intensifies the lament and theological narratives by hiding and revealing. In The Black over the Gold (1992) from the most Catholic of all his series, the floating black inextricably links the darkness of Te Po and Catholic sacredness. In Round Midnight (2000) filled with eloquent gesture, the Roman Cross and the Cross of Lorraine sit in the foreground.

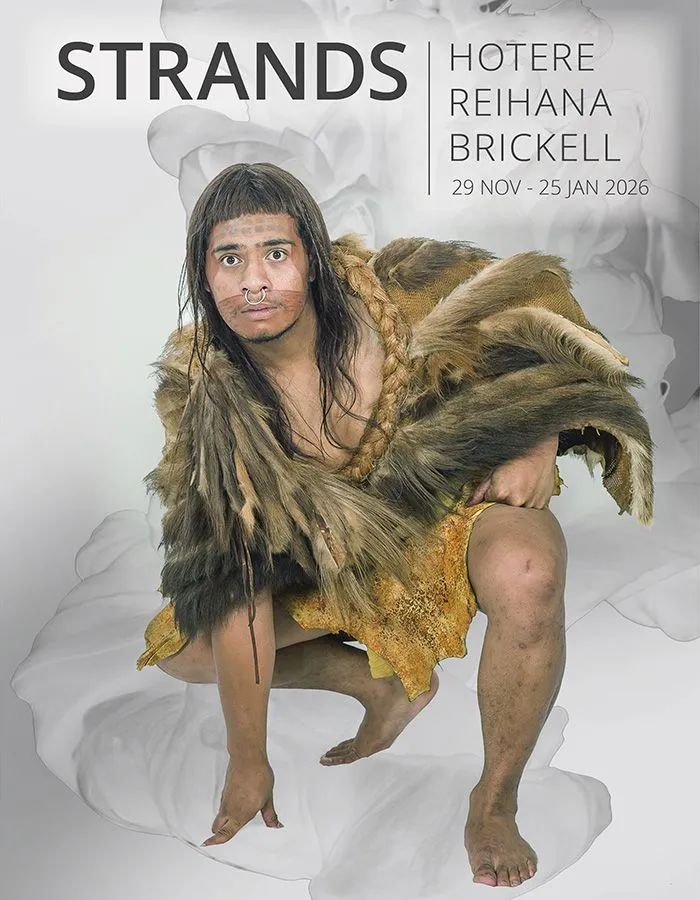

Likewise, Lisa Reihana in her works explores how history and identity are represented while also resolutely expressing Māori cultural values and aesthetics. In this manner, interweaving fact and fiction while confronting colonial narratives, the imperial gaze has been repackaged and turned back on itself. Truth is examined. Both Nootka Warrior (In Pursuit of Venus) (2016) and Joseph Banks (In Pursuit of Venus) (2016) have a deliberate inversion of relationship: the viewer is directly questioned by the subjects’ eyes and demeanour.

In works drawn from Ihi – Mother and Son (2021) Reihana reimagines the creation story of Papatuānuku and Ranginui. Ihi is the division - the separation - between mother and father by their children and the transference of mana and prestige from one generation to another. This group of works is an active assertion of the Māori worldview, the turmoil of birth, as well as the significance of place and belief.

In three new works where each work reflects on atua wāhine (see titling), Heidi Brickell builds threads of connection to stories and sensibilities past and present. Believing art can process things in a way language can’t, Brickell’s works develop different states of being while conflating the spiritual and rational together. Colours and forms slip and slide, shapes resemble or infer unfurling koru, kōwhaiwhai, outstretched hands and so on. Positioned somewhere in the space between European realism and traditional Māori carving, Brickell works up a palette directly referencing the whenua, as well as the sky and sea. She has pioneered in the use of applied thread a continuous line which functions as a plural visual device. Shifts in time seem to emerge, psychological spaces develop where two very different languages both connect yet run completely independently to each other too. This ‘tension’ adds another dynamic into the pictorial ‘environment’ which can’t necessarily be explained but must be experienced. This conversation between interactive experience and the viewer’s imagination is illuminating and becomes exhilarating.