An irresistible critic

Written by

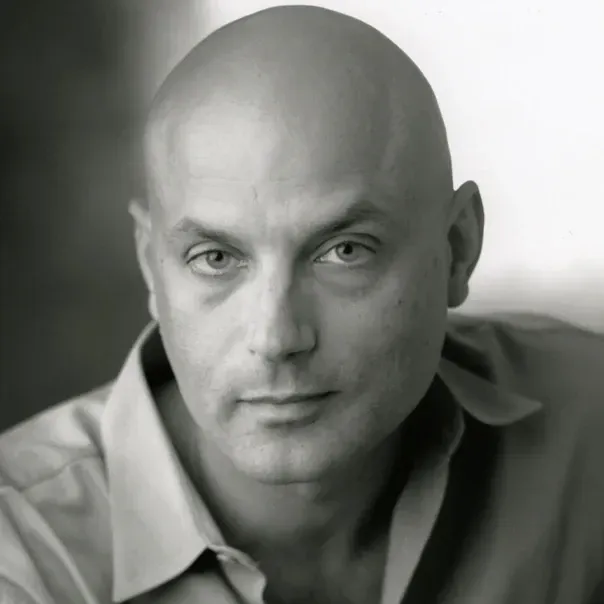

US based writer Daniel Mendelsohn talks criticism and taste with Dione Joseph as he visits NZ for the Auckland Writers Festival.

He recounts the development of his career as a critic, his unchanging concepts of 'meaningful criticism', and the importance of humour.

"Good critics arise at the intersection of expertise and taste: you need both, and the latter, of course, is mysterious - some people just have it, others don’t, and that’s the way it is."

Mendelsohn is a frequent contributor to The New Yorker and has been a prolific writer since his undergraduate days. In his memoir The Lost: A Search for Six of Six Million he excavates his family history while in his essay collection Waiting For The Barbarians he argues that Mad Men are more “melodrama rather than drama”. His new project is a literature-and-life book, recounting the year he spent reading The Odyssey with his late father and the revelations of that experience.

* * *

What were the key moments that steered you towards a career as a critic?

Oddly enough, I’d always wanted to be a critic - many people think it’s a kind of “day job” in between books, but for me it’s the main event just as much as my memoirs and essays. An avid reader of the great critics who appeared in the pages of the New Yorker when I was a teenager, I started writing reviews - just for myself - when I was in college, of things I’d seen or read. Then when I was doing my PhD in Classics in the early 1990s, I started writing critical pieces for a student magazine, and one day the undergraduate editor (who, funny enough, went on to be my editor at the New York Times Magazine years alter) told me, “You know, people will pay you to do this!” And so I started sending pieces out on spec to the Village Voice and other NYC publications, and they started running them, and the ball was rolling. By the mid-1990s I was doing book reviews for the New York Times Book Review, which became a regular perch for me, and then everything else just followed from that.

Tell us about your latest work; what was your process in writing about Sappho?

I’d been wanting to write again about Sappho for years - I published a big piece on her in the early 2000s, when Anne Carson’s translation came out, but that was exclusively literary and focused on the details of the translation, and was fairly technical. (It appeared in the New York Review of Books, my “home” publication.) Then a couple of years ago, when the “new” Sappho poems were discovered, I thought it would be fun to write a piece about what I call “the Sappho phenomenon” - who she was, why her reputation is so large, what these new poems mean, why anyone cares about it - and my wonderful editor at The New Yorker agreed it would be a fun piece, so I got going. As usual, even for subjects I’m pretty intimate with, I base my writing on lots of reading and research - in this case, just to refresh my memory, as it were. I think by the end of that process I had 100 pages of single-spaced notes before I started the actual writing, which is pretty typical - I usually accumulate between 75 and 100 pp. of notes, and that gives me the confidence to put pen to paper.

Have concepts of ‘meaningful criticism’ become more fluid in recent times?

I actually think “meaningful criticism” as I defined it in my New Yorker website A Critic’s Manifesto is unchanging, whatever the revolutions in genre or media may be. As I said in that article, good critics arise at the intersection of expertise and taste: you need both, and the latter, of course, is mysterious - some people just have it, others don’t, and that’s the way it is. I think that as long as a critic is deeply steeped in a subject and can write from profound knowledge, and as long as that expertise is twined with original, interesting, and valid taste (i.e., if you’re too wacky too often, nobody cares what your opinion is!), then you can write about anything, from Twitter novels to Tolstoy, from music videos to Murakami.

Are we making space for nuances that are raised when engaging with forms of aesthetics that operate outside euro-centric paradigms?

I can’t imagine a paradigm - of any culture or modality of thought - that would somehow place itself outside the ability of criticism, as I described it above, to make valid and interesting judgments. If it’s aesthetic or literary or artistic in any way, then it’s potentially subject to rigorous critical judgments. Period.

How important is humor to a critic’s writing style?

I think humor can be a fantastically effective tool in criticism, both effective and entertaining - although I think it’s dangerous, too, because the temptation to be funny at the expense of saying something really useful about a work can be difficult to resist. When the criticism starts to be about the critic’s joke - and I’m sure we can all think of examples! - that’s a problem, because then the writing becomes a showcase for the critic to be an entertainer, and that’s not quite what it should be about. I also think that being funny can often morph into being funny at someone’s expense, which then morphs into just being mean. So humor can lead one down a slippery slope, and should therefore be handled very carefully.

In an age where audiences increasingly have a public voice, what are your thoughts on the notion of the audience as the critic?

Well I think audience and critic will always be two separate and discrete entities - and that’s a good thing. On the one hand, the explosion of the Internet and various social media platforms has made it possible for the first time in history for audiences to participate in the activity of commenting on works of art or popular entertainment en masse, and to be heard - to be part of the public debate. Which is great - I think I, like many professional critics, have learned a lot from being able to see what audiences think.

On the other hand, because critics are professionals who have dedicated themselves to studying and thinking about art in ways most people don’t do, the critic’s judgment will always have a different weight. This isn’t to dismiss audience reactions: I just think now we have access to two kinds of critical responses to things, one professional, one “amateur” (in the good sense of that word). These are complementary, not competitive. A great editor of mine always likes to say that criticism is “a service industry” - the critic has done the work, done the studying, and is thinking things through, working things on behalf of his or her reader.

Where do you see the future of criticism?

I actually am quite optimistic about the future of criticism, precisely because that vast explosion of audience commentaries has, I think, made lots of people MORE interested in just how criticism happens and what are the questions it raises - what are the grounds of valid judgments, where does authority come from, and so forth. So the debate has become richer (if sometimes also more testy), and that can only lead to more thoughtfulness, which in turn will enhance the discourse.

What is your big idea for 2015?

I have only one idea for 2015, which is to finish my book about the year I spent reading The Odyssey with my late father before he died - like my two previous memoirs, a personal narrative wrapped around - what else?! A series of critical reflections about a great text. See what I mean? Nothing I write is wholly free from the critical impulse, the need to read and interpret. What fun!

- See Daniel Mendelsohn at the Auckland Writers Festival on 16 and 17 May.

- Auckland Writers Festival is on 13 - 17 May