Arts Education In Aotearoa - Three Causes For Hope

One arts educator is determined to highlight the positive amid the constant criticism of how the arts are treated in schools.

There has been a lot of talk over the past few years about the parlous state of Arts Education in Aotearoa New Zealand. Even under the leadership of the Ardern regime – which seems like it should have been super-arty (not sure why I think that... perhaps just a vibe?) things have been doldrumming.

Or that is the perception.

Spending time in classrooms as an Education Specialist at Creative Waikato (possibly the best job in the world), I experience something a bit different from the deficit paradigm we often see in the media.

Because teachers actually give an enormous damn about creating creative experiences for Akonga (students).

We can get fixated on the politics of the arts. It’s a catch-all dog-whistle to some sectors of the population – especially in an election year. I get it, some people don’t actually care all that much about creativity – and that’s A-Okay. It’s no more compulsory than enjoying rugby league is in our society (although it is perfectly feasible to enjoy both).

Creativity is important. That statement may be the very definition of preaching to the choir in this instance but it’s obviously true.

Better minds than mine have researched the benefits of a well-funded, well-resourced and well-supported Arts programme. Unfortunately at the present moment, we don’t really have one consistently being rolled out across our country.

A lot of that stems from the fact that with little perceived support from those who could be offering it, schools widely - and teachers in the microcosm - have little in the way of working models for thriving and pedagogically robust arts programmes.

Recently in reaction to OECD statistics, that perennial ‘Educational-Outcomes-Blunt-Instrument’, the ineluctable Christopher Luxon suggested that Maths, Science and English should be taught for an hour each and every day in every classroom in Aotearoa.

It doesn’t take much of a maths genius to work out that this leaves about two hours a day for Technology, Languages, Health and PE, Social Sciences and the Arts. I am a big fan of the STEM subjects. As a teacher in primary school, seeing the vistas that these subjects open up for learners was a huge part of my enjoyment of my mahi.

But as we all know, these ‘knowledges’ are only part of what it takes to be a well-rounded human being.

Creating well-rounded citizens depends on creating well-rounded education systems. Unfortunately in the past couple of decades, the government has tended to throw money at schools and say “Here’s funding. Get it sorted!”. But in the words of education researcher Dr Cathy Wylie, "Just simply saying to schools 'here's money, go and find some support' doesn't necessarily mean they get the right support at the right time or find the right issues."

So yes, from some perspectives, things can look a bit grim right now - but it does seem there is cause for hope. Here are three things to consider before googling ‘where to buy sackcloth and ashes’.

The Ministry does value arts experiences and education

No wait! Hear me out - put down that pitchfork!

Creatives in Schools, an educational ‘artist in residence’ programme funded by the Ministry of Education ‘aims to provide creative learning experiences that enhance the wellbeing of students and ākonga and develop their knowledge and skills in communication, collaboration, and creative thinking and practice’.

Funding for Creatives in Schools gradually rose from $340,000 in 2020 to $3,400,000 in 2023. The good news is that ‘The Powers’ have announced round five of this programme which will hit the ground in 2024.

Creative in Schools proves that if something works - it spurs the bean-counters on to new funding. We just need to find ways of reporting that appeal to accountants who - sorry to any accountants who might be reading this - aren’t historically overrepresented in the creative arts.

We can already see that it works through different artforms and different creative approaches - including murals, theatre shows, musical projects and more. Let’s celebrate those stories and encourage more activity like that taking place.

I would suggest that it may be time for academics in the educational sector to spend some time on further honing ways in which to measure the more esoteric benefits of a robust arts curriculum - ways of measuring which merge financial and emotional/health benefits of creativity.

Some have tried but we are still without a generally accepted measure of the benefits of arts programmes outside of blunt instrument, traditional assessment models. Anyone want to fund my course cost for 4 years? I’m keen…

The desire is there

There is a passion in schools to provide students with quality educational experiences across all curriculum areas.

I have been lucky enough to both be a teacher and to work with teachers for the past twenty years. Even under the most trying of conditions and under constant bombardment of negativity about how crappy their sector is, teachers just keep…on…teaching.

They provide educative experiences to our children in preparation for a world that is not yet clearly defined. That’s a big job.

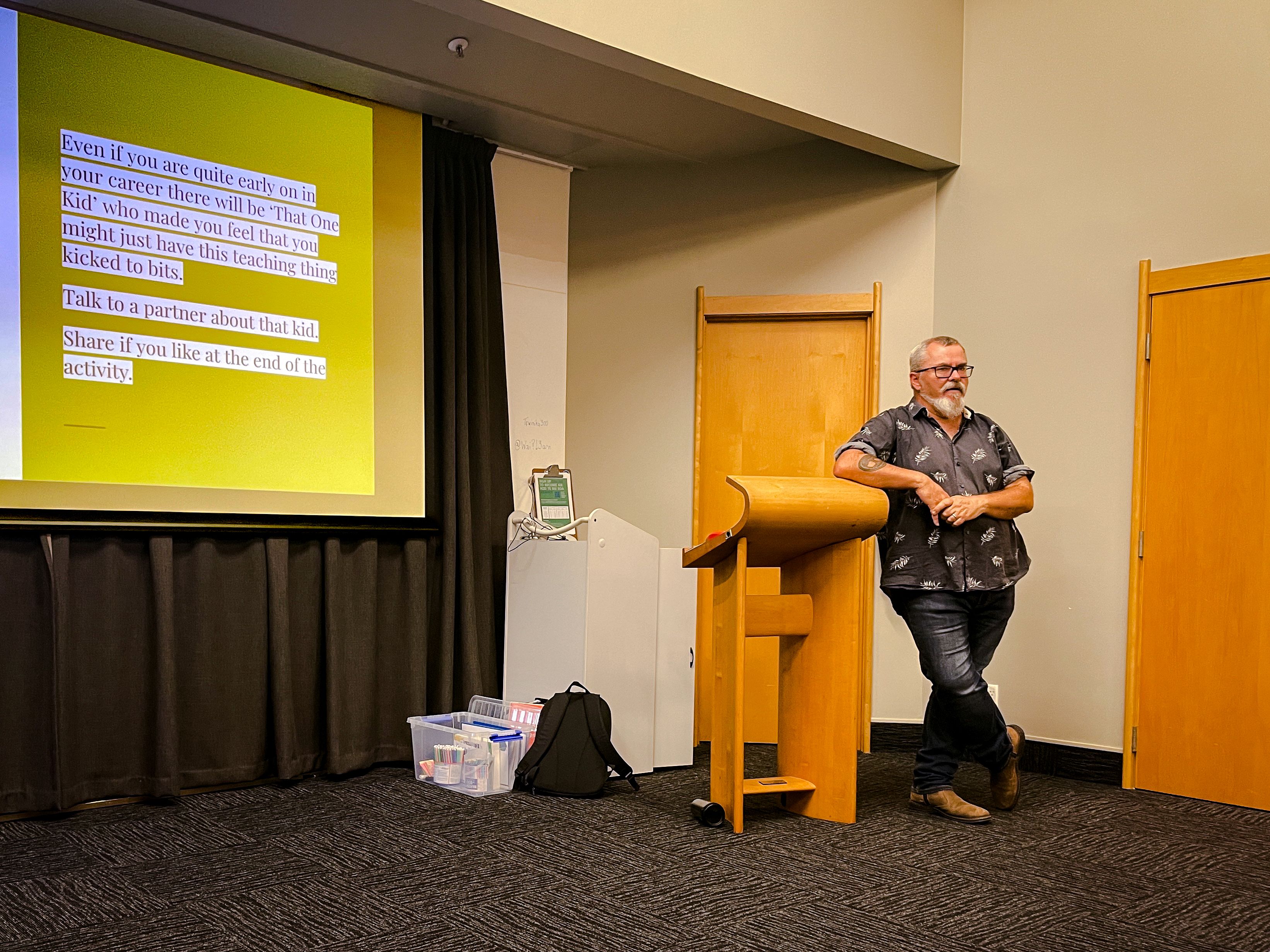

In delivering the Integrated Creativity Resource to schools over the past year, I have been struck by just how ready teachers and administrators are for picking up and running with anything that enhances their ability to deliver creative experiences to their students.

The past three years have been a siloing and isolating era and schools are ready to innovate. This is also supported by work explored by Te Rito Toi and The Chartwell Project.

They’re tired, a bit bored by criticism and under-resourced but, by jingo, they are ready.

Points of crisis are opportunities for innovation

Human history is littered with horrible events that have fostered positive social change. People have an innate desire to turn a negative into a positive.

If we consider the current state of arts and general education in Aotearoa New Zealand to be a crisis, then we are in a great position to look at it as an opportunity for positive change.

At the heart of turning crisis into opportunity is mental reframing. We can sit about wailing and groaning about how awful everything is (It’s not actually that bad by the way - just saying) or we can look at the problems and find ways to solve them.

All this will take creativity, bipartisan future-views and optimism.

So, if we remember that we have: a Ministry that rewards success; a work-force that is ready to innovate; and, an almost unique time in history where everything has almost been torn down ready to be built again in a slightly more user-friendly way - this is the recipe for a vibrant, creative education system for the future which is creativity-centric.

Systemic change takes time and it is often driven by innovators who do the work behind the scenes, slowly developing programmes that have proven positive outcomes before they are presented to those who will fund them going forward.

There are lots of these little programmes popping up in communities and schools all around - especially if we go looking for them. The next step is to find and invest in those strengths to support them to continue developing, refining and implementing this awesome mahi.

Because if we look at these things as opportunities rather than social deficits, we can make changes. Teachers and others in Aotearoa are innovating their hearts out in creativity education. Let’s share those stories and use them to inspire others (and further investment).

Prophecies are often self-fulfilling and malleable. We can set our outcomes by adjusting our prophecies. Right now what is needed is the ability to see a bright future in a moment of crisis.

Nick Clothier is the Creative Education Specialist at Creative Waikato. He is an artist and has a background in teaching. Nick’s mahi combines his background in education and the strength-based practice of social work to develop teaching capacities in the arts for kaiako in the Waikato region.