At the Feet of a Master

Written by

If you’ve been reading The Big Idea over the last six months or so, we’ve been dissecting the state of mainstream arts criticism in our country.

This ongoing conversation makes the recent appearance of UK art critic and master reviewer Charles Darwent at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki even more pertinent.

Dotted amongst the crowd of art enthusiasts who attended Darwent’s conversation were movers and shakers within New Zealand’s art scene. These included luminary artists Gretchen Albrecht, Stephen Bambury, Tony Lane and Denys Watkins, director of Te Uru Andrew Clifford and Art News publisher Brenda Chappell. The breadth of their collective experience not only spoke to the gravitas of Darwent’s appearance, it alluded to the significance of good art criticism to keep the entire sector turning.

A potted history

Darwent has made a name for himself by penning informative, accessible pieces for a who’s who of mainstream and specialist media – the Guardian, the Art Newspaper and Art Review. Between 1999 and 2013, he held the coveted spot of the Independent on Sunday’s chief art critic before swiftly turning his hand to the small screen, presenting the Netflix series Raiders of the Lost Art between 2014 and 2016.

Proving that he is a master of all trades, Darwent has also written a number of books, including Mondrian in London: How British Art Nearly Became Modern and The Drawing Book: A Survey of Drawing.

From the Bauhaus to Black Mountain College

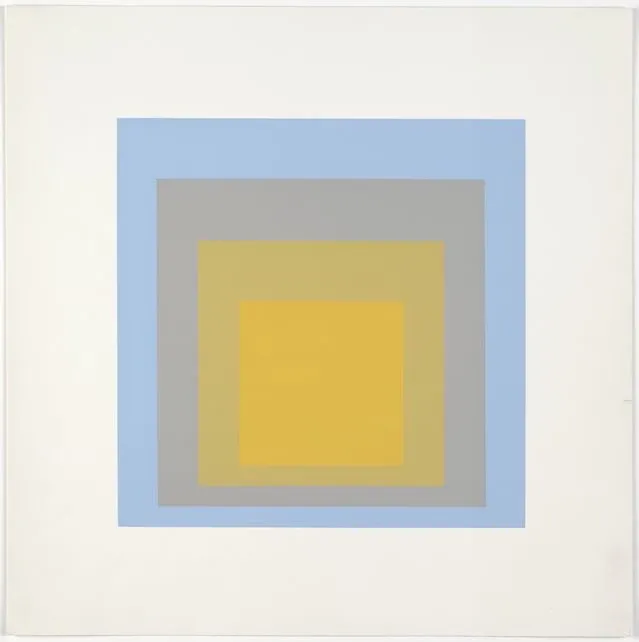

His most recent offering Josef Albers: Life and Work was published last year and underpinned much of his conversation with Auckland Art Gallery Curator (New Zealand art) Julia Waite. A German/American artist and educator, Albers was a key figure in the Bauhaus, a German art school that championed modernity from its art to its architecture. He went on to head the immensely influential Black Mountain College in North Carolina.

Darwent describes Albers teaching style as “unconventional – he taught through gesture, not words.” However questionable his methods were, they were not without impact. Albers left his mark on some of the greatest canvases of modern art, with Kandinsky, Klee, Rauschenberg and Twombly amongst his luminous roll call of alumni.

The book was described by Waite as “interrupting my life in the most positive way – I wanted to run away and join the Bauhaus. [Darwent’s] writing has the capacity to get the blood pumping.” Originally, Darwent did not intend to write a book about the Bauhaus. But he found himself at the Josef Albers Foundation in Connecticut putting the final touches on Mondrian in London when he (along with every other critic writing for the Independent) found himself out of a job. Darwent was swiftly approached by the Director to write Albers biography, leading to a period he describes as “the most interesting four years of my career” with its release coinciding with the centenary of Bauhaus.

Over the course of the evening, Darwent kept the audience entertained with his quintessentially dry English wit and astute handle on a deeply complicated man who Darwent describes as “a moralist in paint” the relationships that shaped him and an ever-evolving artistic landscape.

Foxes and hounds

Currently, Darwent finds himself in the “lucky position where I get to write about what I like”. When asked for advice for those looking to make a career as an art critic, he sardonically responds “Don’t. It’s becoming increasingly difficult because of social media to make a career out of it. What happened to me [at the aforementioned Independent] was they decided we were expendable because everyone has a view and it’s out there on social media...

But don’t hang out with artists would be my real piece of advice for unsuspecting young art critics. Because you can’t both ride with the hounds and run with the fox. You can’t write proper disinterested criticism if you’re pals with the artist."

Social Media Explosion

For Darwent, the “explosion of social media” comes with its pros and cons – “it means that people mightn’t have the body of knowledge to be a critic, but it also means that more people get to share their views. People have to shop around and choose carefully”

What makes a good art critic?

When The Big Idea asked Waite what makes a good art critic, she earmarked three main qualities and characteristics: “They should have a broad knowledge of art history and different forms of art, the flexibility of mind and ability to see things from multiple perspectives and finally the bravery and independence to not always run with the pack. One doesn’t want to be beholden to the artist.”

Reflecting on his writing process, and his own “forensic” writing style, Darwent says “I was one of those critics who did their homework. I liked to know something about what I was writing about. The nature of newspaper criticism is that one day you’re writing about Rubens drawings, the next week you’re writing about Tracey Emin’s bed, the week after that you’re writing about Matisse – you can’t possibly know all those things."

And the kitchen sink

"The wife of another critic described me as “Mr. on one hand…. and on the other". I did try to be even-handed. But my real writing process is every five minutes I think oh that cupboard under the sink is looking untidy – like everybody else I think”

To understand both Albers and wider arts issues through Darwent’s lens was a rare treat. Here’s hoping that the value of the art reviewer, biographer and columnist was rekindled for the sector in New Zealand that balmy Autumn night.

Kate Powell writes our column 'Tough Crowd' which has been a direct response to real concern in the sector about lack of review.

Images credits, from the top:

Charles Darwent and Julia Waite in conversation. Image supplied by Auckland Art Gallery

Book cover, Josef Albers: Life and Work

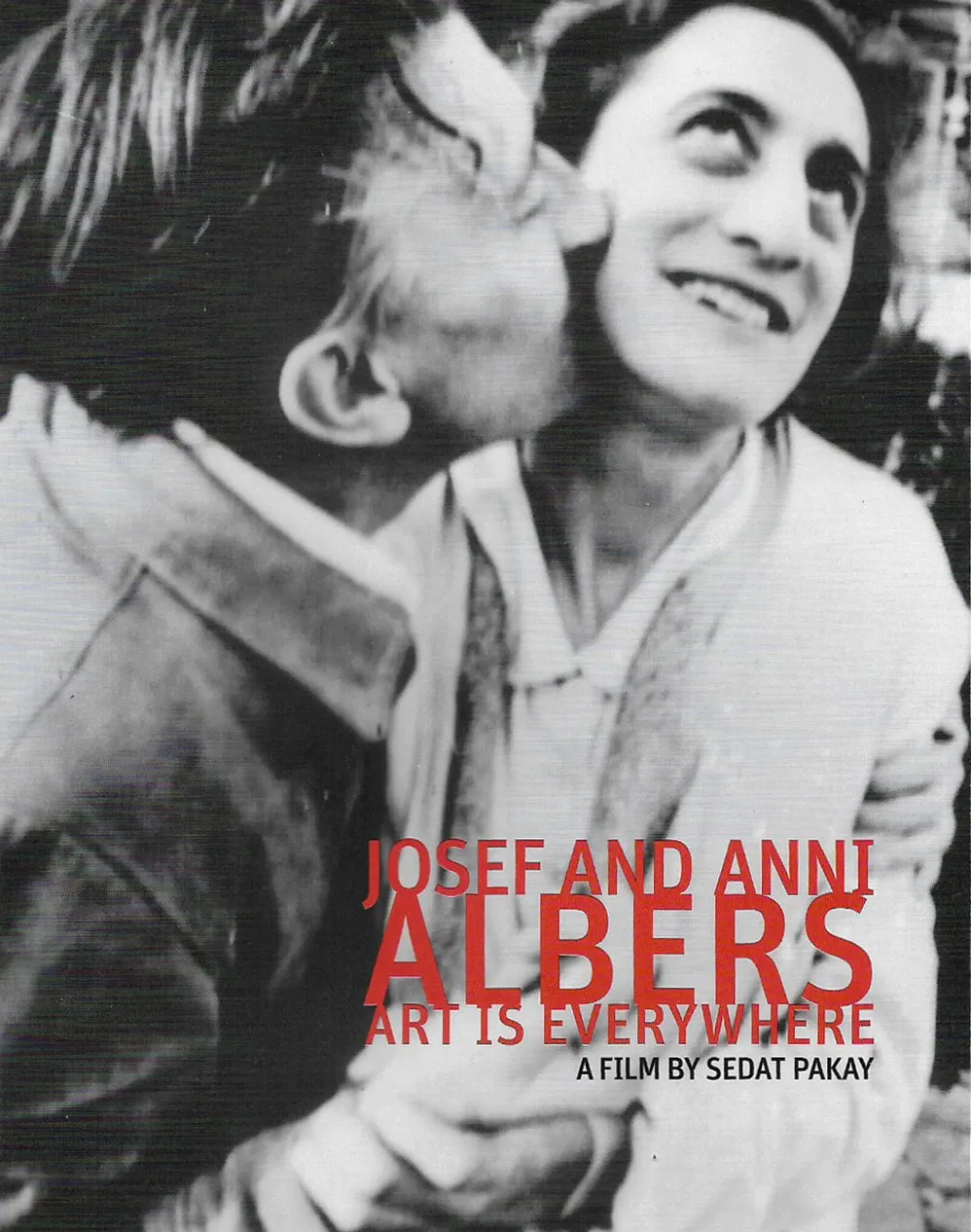

Josef and Anni Albers, hero image for film by Sedat Pakay

Josef Albers, Homage to the Square: Ten Works by Josef Albers, 1962. Courtesy of MoMA

Charles Darwent in front of Anish Kapoor's sculpture at Gibbs Farm, Kaipara Harbour. Image: Jennifer Buckley

The Bauhaus building in Dessau, Germany, designed by Walter Gropius, housed the school from 1925 to 1932. Jens Schlueter/Getty Images