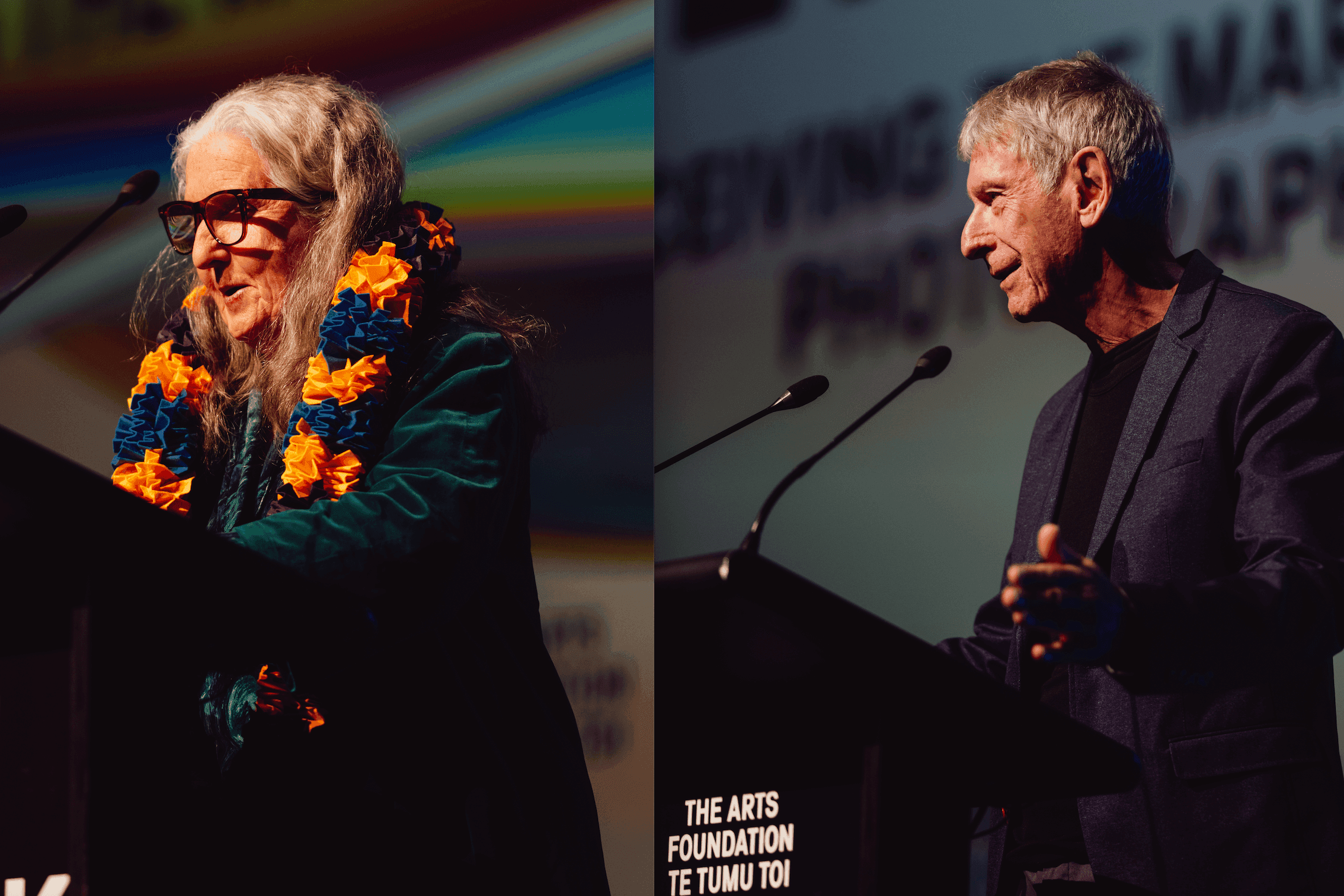

Clark And Black: Lessons From Laureates

The magic of photography has cast an enduring spell for these two greats of the genre - Chris Forster sat down with them to reflect on their careers and found there's no slowing them down.

Written by

Fiona Clark and Peter Black have captured some of Aotearoa’s most vibrant, transformative images - from very different points of view.

And there’s no sign of easing off on their remarkable careers, which each span nearly half a century, after elevating photography’s national exposure by collecting two of the 2023 Arts Laureate awards.

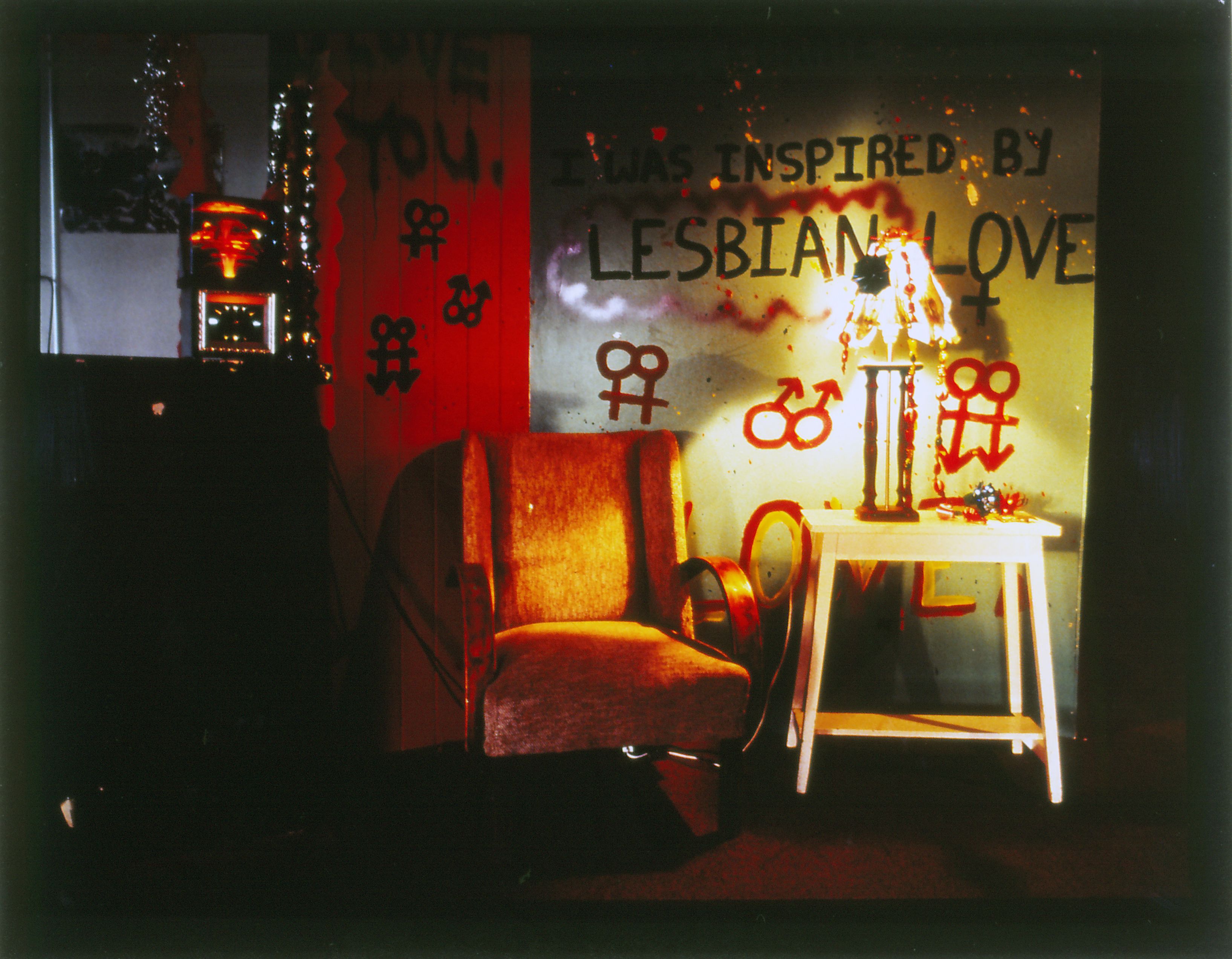

Clark broke new ground with her vivid images from inside Auckland’s lesbian, gay and transsexual scene in the repressive 1970s, and went on to take candid shots of professional bodybuilders, HIV sufferers and the rights of local iwi.

Black is acclaimed for his ability to take extraordinary shots of Aotearoa’s ordinary people, buildings, happenings and landscapes, with an extensive catalogue of photo books and has featured in numerous exhibitions at the nation’s foremost galleries.

The Big Idea captured their indomitable spirit and unshakable belief during an extraordinary conversation in the lounge of a downtown hotel, on a crisp Auckland morning.

Won't back down

Fiona Clark has a bee in her bonnet.

Never afraid to stand up for what she believes in - Clark is currently a formidable adversary for the energy industry in Taranaki.

She’s refusing to buckle in the latest issue to emerge from her ongoing battle with local authorities and the energy companies, who dominate the landscape close to her long-time home and studio at the historic Tikorangi Dairy Factory, inland from Waitara.

She didn’t take long to hone in on the jarring details.

“Believe it or not, someone complained about my roadside plantings of native trees. So they took it seriously about what they called unauthorised plantings.

"I live near seven oil wells so I thought the oil industry is really trying to poke me again. I dug them out (the offending trees) last Sunday. So I authorised them - 22 in all - took photographs of them all and I will exhibit them”.

For over four decades, Clark has produced unflinching and engaging images of bodies generally avoided by the public gaze, forged by the uproar over shots from inside the drag community in the unforgiving and conservative 1970s.

It’s this potent blend of visual activism that elevated her to Laureate status with the My ART Visual Arts Award.

Keeping it real

Peter Black is fiercely committed in his own way to his vision and focus on capturing Aotearoa’s social landscape - and he richly deserves his recognition as the latest recipient of The Marti Friedlander Photographic Award.

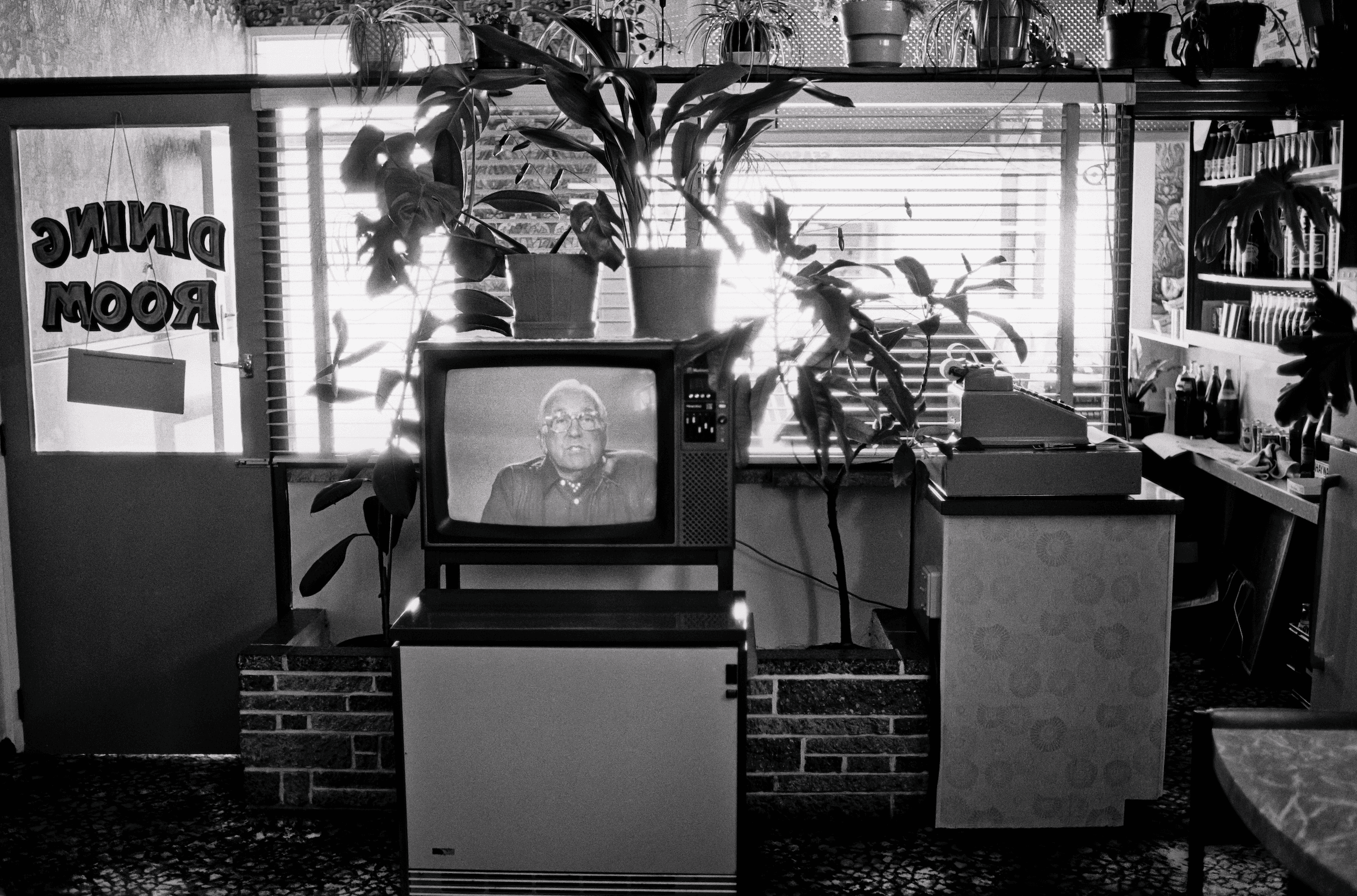

Unlike Clark, there’s nothing overtly political about his work or his approach but he is keen to rework a famous project of his from the recessionary mid-80s, Moving Pictures, which has contemporary overtones.

“There was great upheaval in New Zealand - a lot of social issues going on - and the country felt like a gloomy sort of period.

"It still seems to be relevant I think.

"We set off in a car .. you could actually feel it. The photos have that kind of black-and-white grainy look about them that lends to that atmosphere as well.

"The atmosphere felt almost like it does now with the possibility of a National government hovering in the wings.”

Photographs from this era like Dog and Mercedes Benz, Samoan Twins and Selwyn Toogood (above) encapsulate Black’s ongoing quest to capture perfect moments with precise timing.

“I have several things I try to avoid in my photos. That is any famous people, any people in the media or somebody that has that media presence.

"I’m just after the ordinary person - that’s what my photos are about. That ordinary person can be a rich person or somebody who’s not rich, or in between. But if they’re famous they do not interest me. There’s enough photos of these people around anyway … I want them to be democratic and that’s the whole purpose of my photography.

“That’s one of the great mysteries of the medium of photography when you believe in something and you’re doing it properly … photos can mirror something, not the truth, but something important and something vital.

It is the greatest medium in the world. There’s nothing to compare to it, in my book. That’s why we’re doing it, Magical is the word.

Clark agrees. “Art is magical .. making art that connects with other people. You can wet your pants with it. That’s a saying from David Brown in the 70s, who’s part of the early gay lib.

"You can go to an art gallery and view a piece of art work .. only one in an exhibition - blow your mind, create a discussion in your brain. The whole bit over human connection.

That’s extraordinary that we can do that.”

The threat ahead

The conversation switches to the impact of technology on these established veterans. Digitally altered images and social media snaps threaten the existence and appreciation of one-shot photography, and the threat of AI looms large.

Black muses “With AI, I’m slightly worried that all the manipulation of it will go in a terrible direction.

"Fiona and I’s work will no longer be held up as a little truth.

"Photography’s never been about the truth. It’s about an impression you have and the person behind the camera … everything is different from two different photographs. You can take an image from something over there but the photos will look different."

Black does use Instagram to promote self-published books and remains hopeful the threat will pass, as it did with Photoshop earlier this century.

“Well, we got over that pretty quickly. It still looks like photography to me. It doesn’t matter if it’s digital or analogue, it makes no difference because in the end, you’re looking at an image in a book or an exhibition, maybe on a screen. You can’t tell really what the medium is and it’s really irrelevant.

What is important is the image itself.”

Clark takes a more adversarial approach, switching to another problem rife in the digital age, after recently dealing with a copyright issue.

“I'm very specific about where the images are, who uses them and the context they’re used in. If a gallery posts a collection or digitalises a publication of mine, I’m going to get a bit snotty.

"Like a gallery publishing a whole collection of GO GIRL and that leads to AI .. because you could download any image and tweak it up.

"I just remind people I’m still alive. When you are alive you can make a choice, you can give it away if you want. But I can’t.”

Defying definition

A quote discussing Fiona Clark’s work sparked a fiery response. The summation in an Ian Wedde essay claimed there are two kinds of photographers - one motivated by empathy, the other by stealth. He implied that Clark has qualities of both.

“The way I work, you can’t box it. (Curator) Peter Ireland has written about me, really succinctly, you can’t stick me in a box.

That's why being a visual artist is really important to me - because I’ve never seen myself in the box. I’ve never ever been that, whether it’s gender, my work, my practice .. I’ve never seen myself that way.

"I do have empathy, yeah. I do know how to take a photo. And I do know how to present it.”

Black bristled at the suggestion and the use of the word stealth from a profession he loves deeply.

“I hate the word because it’s the opposite of how I go about it, to be quite honest.

"I’m not hiding with a telephoto lens, I just go out with the normal 50 mil lens on my camera - I have to get close to people. I’m not hiding anywhere, the camera is very obvious. Stealth is not there (laughs). I’m very visible. I want to be visible.

"I want reactions, sometimes I want to talk to them and explain what I’m doing.”

It was remarkable to be given the chance to capture the thoughts in audio and written form about the ongoing brilliance of two remarkable characters with an unerring eye for details, emotions, characters and all the wonder that can be captured in a brief moment.

Their legacy is clear during the later stages of their respective careers.

Fiona Clark will always be about capturing marginalised people in a positive light.

“I try and make sure we have identity. Who we are dominates the work - so you, as another person viewing, engage. That’s my mission really - engagement - which is a very political act. It’s like performance work. People engage with the performer.”

Peter Black retains his vision of the rationale behind his unique photographs.

“When I talk with very young photographers, I try to say to them that if you have demons in your head that say to you 'I’m going to be assaulted if I take a shot of this person or I’m going to have a really bad experience and the person’s going to react badly to me' - if you have all those thoughts in your head, you’ll never take a photo.”