Bridget Williams: The value of knowledge

Written by

Of all the awards and acclaim that Bridget Williams MBE ONZM has received for her work as an editor and publisher, the honorary doctorate from the University of Otago is, without doubt, one of the most special.

Not only because she now shares the honour with the likes of Janet Frame, Ralph Hotere, Hone Tuwhare and Charles, Prince of Wales.

Not only because the university was her alma mater, or that her late father Robin Williams was a former Vice-Chancellor who was also conferred an honorary doctorate in 1972.

Mainly the honour is special because it recognises the intellectual value of her work.

Her company BWB (Bridget Williams Books) will mark three decades in September next year. They are decades in which she has sought out writers and scholars, and encouraged them in the telling of New Zealand stories, “deepening our understanding of what it is to inhabit these islands.” Announcing her doctorate, the University of Otago says Williams has been hugely influential, playing an integral role in starting public conversations in New Zealand about our history and identity-shaping intellectual life and cultural debate.’

The 71-year-old says she values knowledge ‘as the intellectual imagination'. “I’m naturally curious. That’s probably the thing about me. I read all the time. I have a very deep commitment to the value of knowledge, it’s at the centre of everything I do. I think having an independent place for a New Zealand voice is valued.”

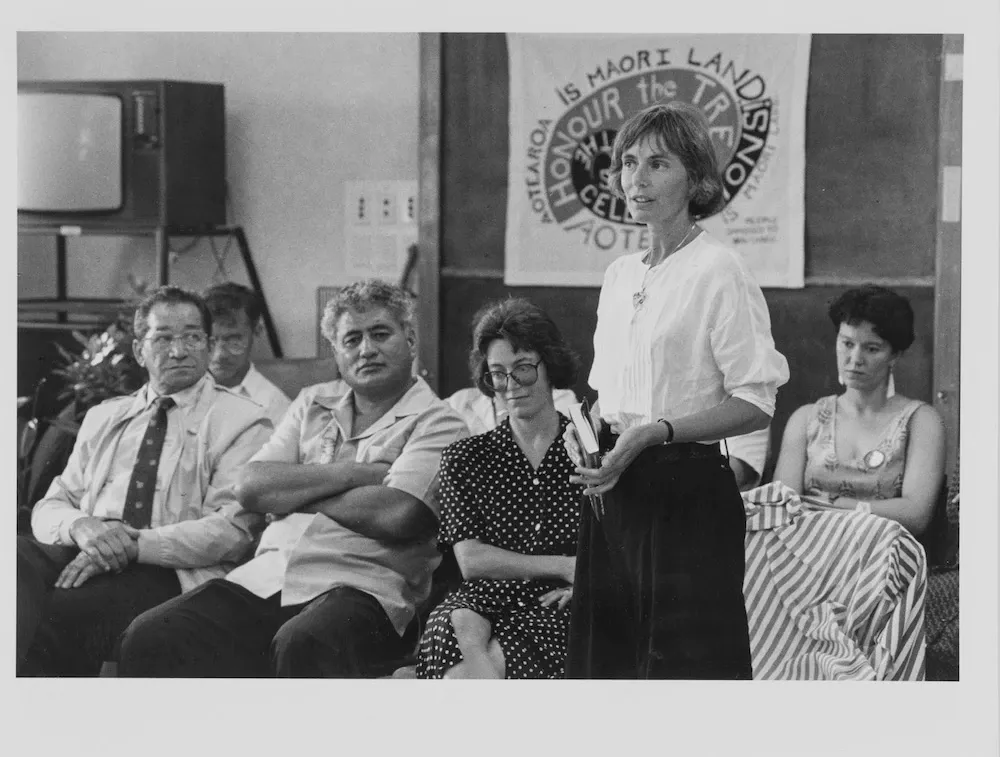

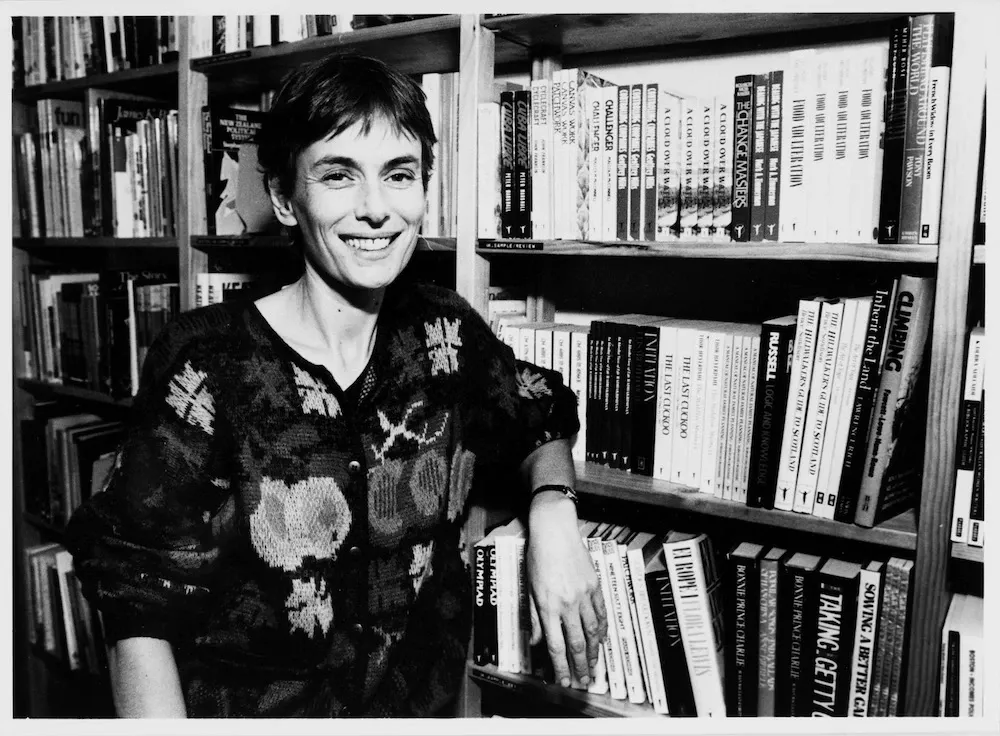

Bridget in Palmerston North in 1990 - on tour with the Listener Women’s Book Festival the week after confirming the set-up of BWB. Image/BWB

Her respect for learning is likely inherited. A strong thread of academia pulls all the way from her childhood. “There were always books in the house and a very strong emphasis on education. My father was a mathematician, and we had to learn our times tables very, very thoroughly – we were tested before breakfast.”

She’s keen to stress it wasn’t always sums and science but says doing things in a well-researched and thorough way, is built into her DNA. “We have, perhaps to a fault, a kind of perfectionism in our family. We did Latin, and my father insisted his daughters do science. So, I did physics and maths all the way through school even though I never intended to continue with those subjects.”

Bridget took her Otago degree in English literature to the United Kingdom in the late 1960s and worked in Oxford for several years as a research assistant to scholar and author Dame Helen Gardner.

Returning home in 1976 she worked for the Oxford University Press in Wellington. Five years later, aged just 33, she set up Port Nicholson Press with legendary bookseller, the late Roy Parsons, and designer Lindsay Missen.

Years of creativity and capital

Williams says she didn’t set out to become an independent publisher “as a great vision” it just happened. “I went here, I went there, and gained experience which enabled me to do the things that I’ve done as an independent, so it’s a sort of winding path.”

A path that she admits has been “pretty scary along the way” at certain times.

“Publishing exists in both the commercial space and the intellectual space, and we have to be effective in both or we wouldn’t survive. It hasn’t always been easy to find a way forward.”

When she started the Port Nicholson Press, it was with Roy Parsons because she says, she didn’t know anything about the business at all.

“I didn’t know how to write an invoice. I didn’t know what cash flow was. And I needed somebody who would teach me all of this.”

Williams at a Jane Kelsey book launch in the late 1980s. Image/BWB

In 1984 she sold Port Nicholson Press to Allen & Unwin Australia and became managing director of the newly formed Allen & Unwin New Zealand which incorporated Port Nicholson Press.

Six years later when the parent company in the United Kingdom changed hands, she bought out their “list” of New Zealand published titles, and set up, again, in her own right, as Bridget Williams Books (BWB).

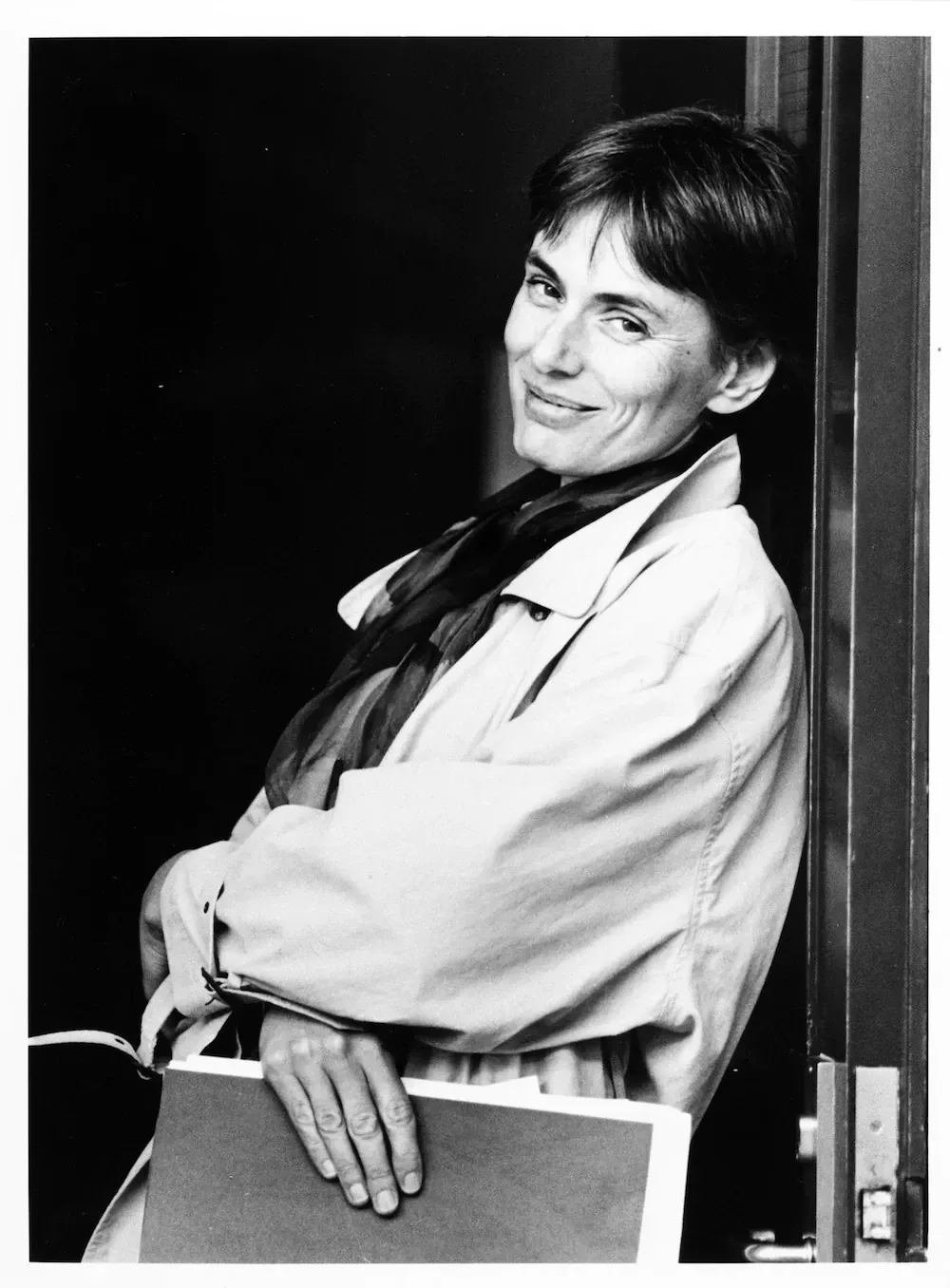

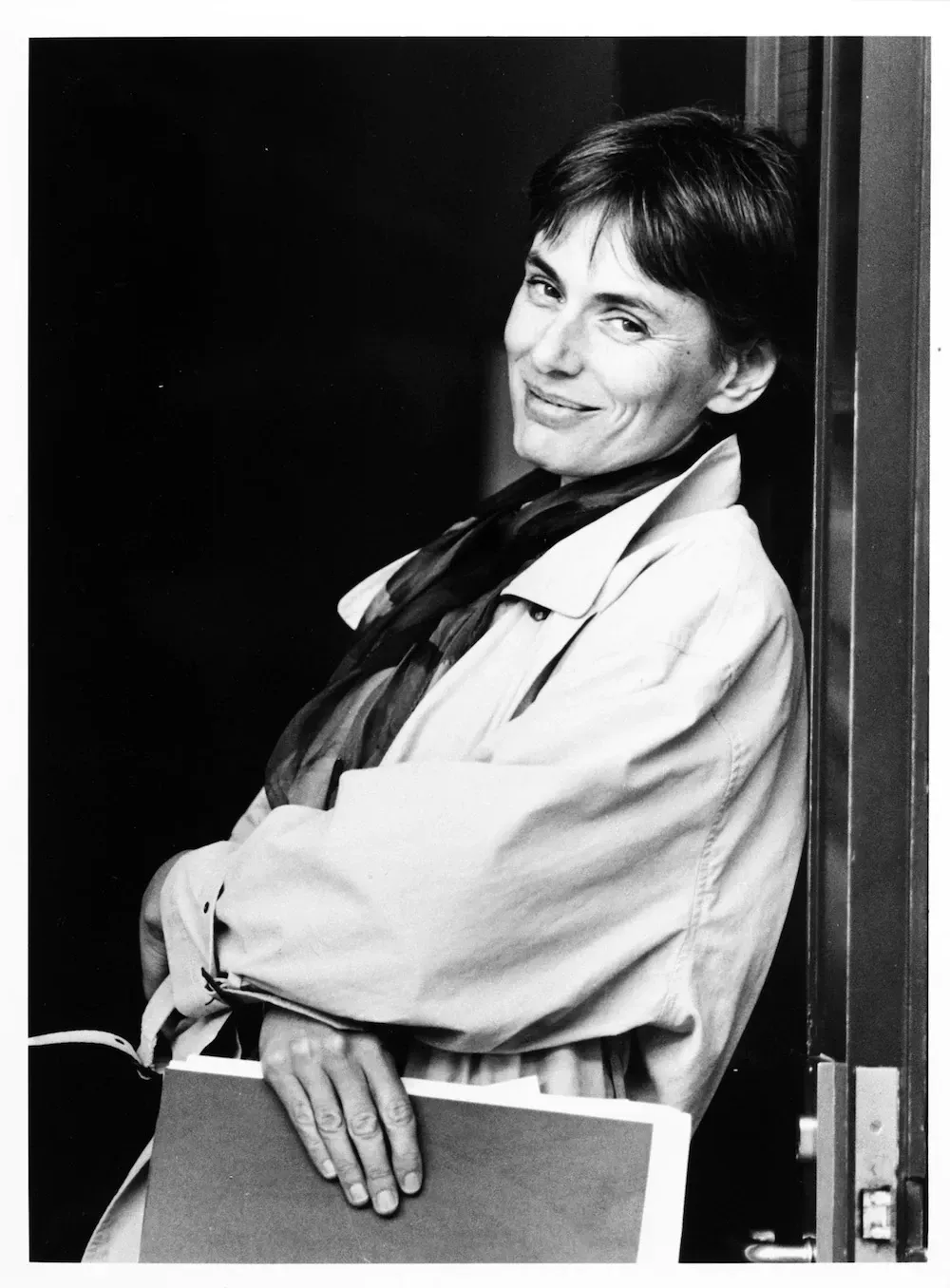

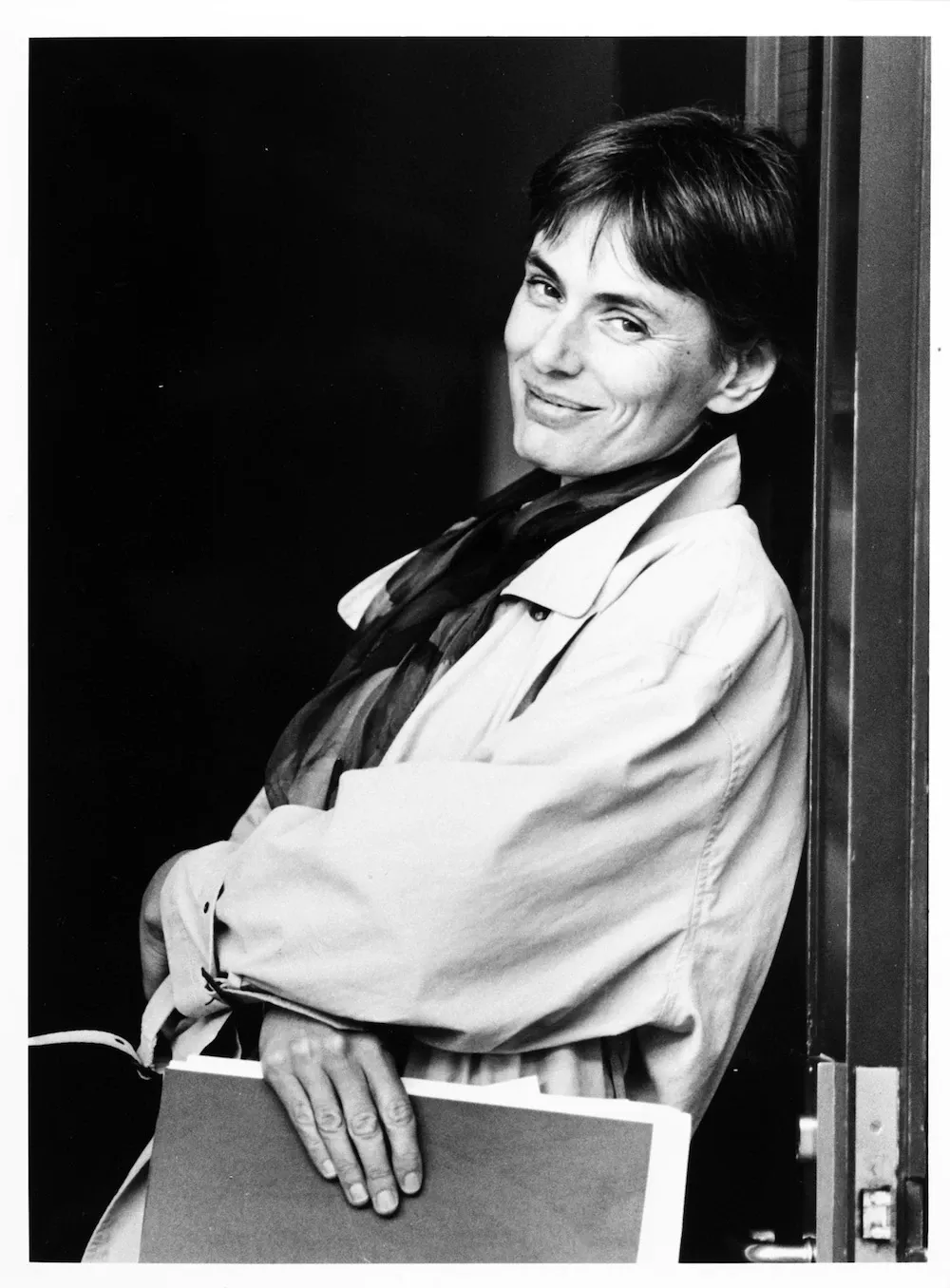

As a young managing director, Allen & Unwin New Zealand in the 1980s.

“It’s a kind of pattern of the industry – creativity and capital. When I bought the list, and I had to make a decision because the company was disappearing under my feet, I was 51% in favour of doing it. I knew how hard it would be.”

One question she had starting BWB was what impact the change may have. “I was publishing books the next day but I had that quite strong sense that serious authors might not publish with BWB because we weren’t international anymore.”

A month on, historian Judith Binney sent her a handwritten note suggesting they meet. She was ready to talk about the book that became Redemption Songs, on the life of Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki.

“At that point, this book, any publisher in the country would have published that book. That was pretty cool and it was a real gesture of faith – also a gesture of support for an independent firm.”

“The world hasn’t changed as much as people might like to think. People really want to write, read and publish books that’s my fundamental belief.” Bridget Williams

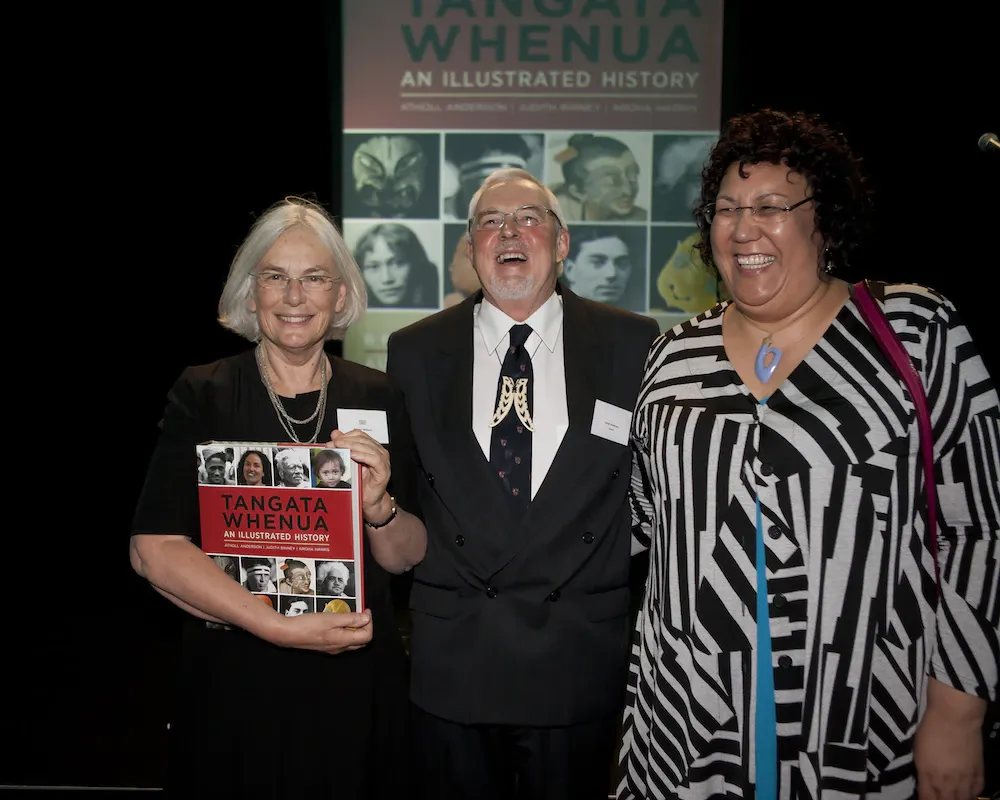

Redemption Songs won Montana Book of the Year in 1996 and is one on a long list of landmark BWB titles. It was a significant step toward more publishing with, and for, the Māori world. Work which Williams had begun with projects such as the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography and its volumes in te reo Māori; with titles such as The Book of New Zealand Women/Ko Kui Ma Te Kaupapa and in 2014 Tangata Whenua: An Illustrated History. “My books have taken me closer than I was to the Māori world and I deeply appreciate that connectivity.”

Bridget Williams, Atholl Anderson and Aroha Harris at the launch of Tangata Whenua in 2014. Image-Aaron Smale/BWB

Sustaining the work

There have been increasing challenges for publishers around the world over the past two decades – from globalisation to the recession and the digital revolution.

In our small New Zealand market, it eventually became clear there was a need for stronger financial support for the serious non-fiction BWB publishes.

By 2006 the BWB Publishing Trust had been set up to develop the funding to ensure that this work would continue.

“It was a big shift for me. I was really proud that we’d always made it all work as a sustainable independent entity. For me to say ‘okay we’re going to need funding to make this work’ was a big step and a big transition.”

Now she’s looking forward to another transition – stepping back gradually from management and handing over to BWB publisher, Tom Rennie.

BWB publisher Tom Rennie has a long connection with the company after starting as an intern out of university.

He returned in 2011 after working several years for educational publisher Cengage in London. Image-Aaron Smale/BWB

“People kept saying to me when are you going to retire and you think ‘why would I want to stop doing this?’ I do want to stop doing some of the work but it’s such a pleasure to be here. There’s a lot of energy about what could happen here in publishing, and a whole generation of writers and thinkers coming through. It’s very valuable for me personally to be involved with that forward-looking activity.”

Story by Keri Malthus