Colin McCahon - revered and criticised

Written by

The name Colin McCahon has practically become a synonym for modern New Zealand art.

His 45-year career was one of perpetual metamorphosis; merging Christianity, Māori language and legends and a healthy dose of European and American modernism. The result was an oeuvre of works that spoke as much to one man's existential struggle as it did to a nation struggling to emancipate itself from an identity dictated by Imperialist Britain.

As with most art that is bold in its intent, screeds of essays have been written and miles of exhibitions hung in McCahon’s wake, making him revered and criticised in equal measures. Under the postcolonial lens of the 1980s and 1990s for example, McCahon was demarcated as a “settler artist” who laid claim to land without considering tangata whenua. While his specific take on biculturalism - one that was intertwined with Christianity, a tool of colonialism - raised eyebrows.

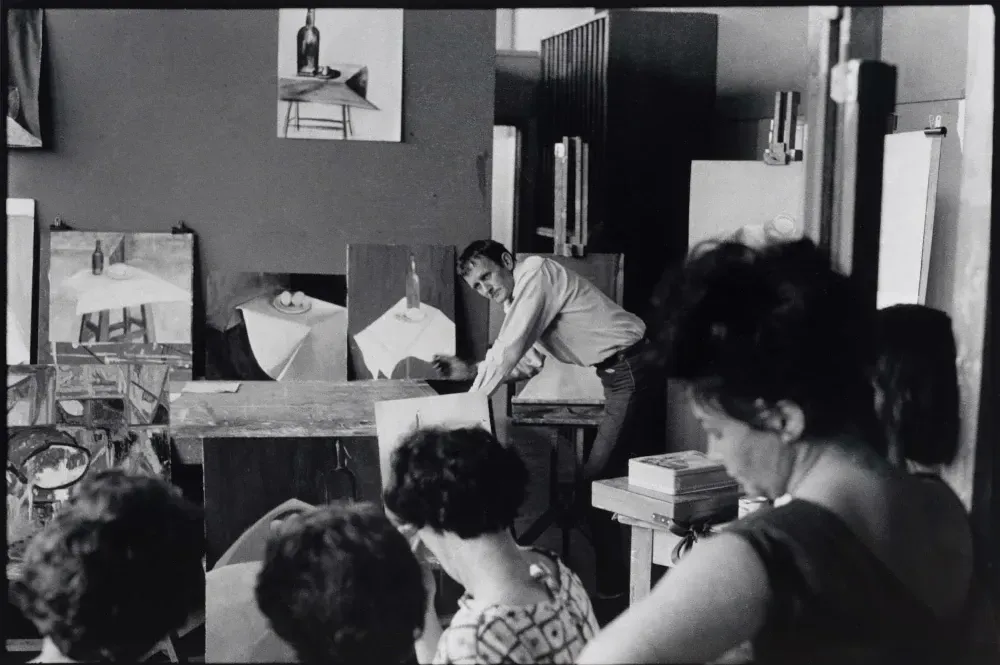

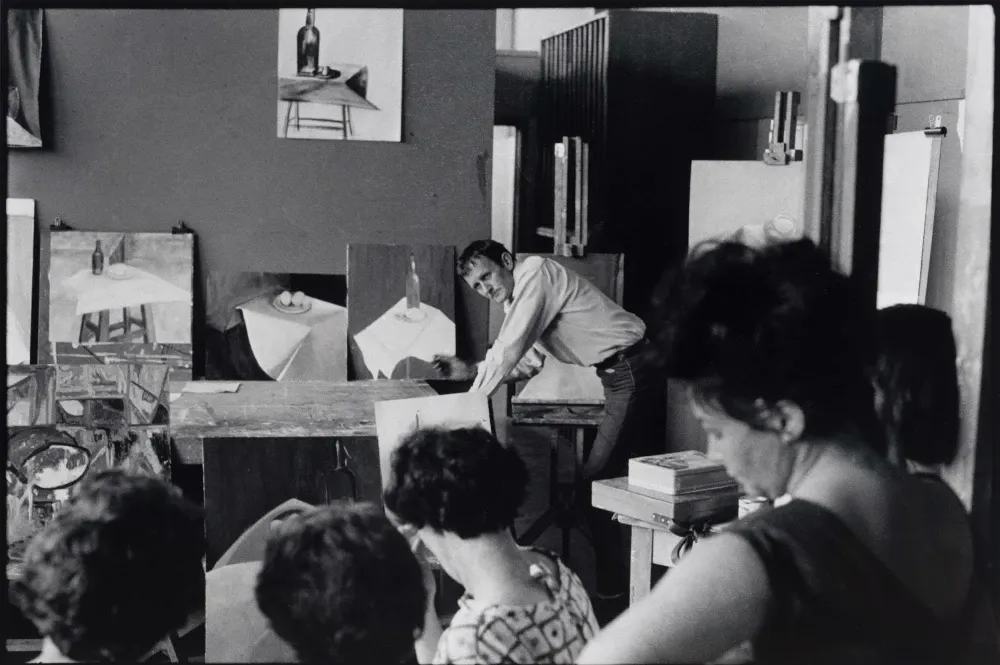

Stuart Pilkington, Colin McCahon at Elam, 1967. Supplied.

Expert curation

Because McCahon is such a canonical figure, making fresh curatorial decisions is difficult. For his centenary, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki explores the impact that ‘place’ has on McCahon’s work with A Place to Paint: Colin McCahon in Auckland. While the exploration of place isn’t a new curatorial device, what this exhibition does well is capture McCahon’s major aesthetic and thematic developments over a 30-year period.

With just 25 paintings spread over three rooms, A Place to Paint has been expertly curated by Ron Brownson and Julia Waite. They appear to have taken their cue from McCahon himself who said “my paintings are almost entirely autobiographical - it tells you where I am at any given time, where I am living and the direction I am pointing in.”

The exhibition covers McCahon’s time in Auckland between the early 1950s until the 1970s, with each room focussing on an individual decade. This was a clever move for two reasons. Firstly, it gives each work the physical space to be considered as an individual piece as well as a collective whole. Secondly, it gives the viewer space to consider the unique contexts that the works were made in and how they shaped his artwork. Each room resounds with an energy unique to the period it was created in.

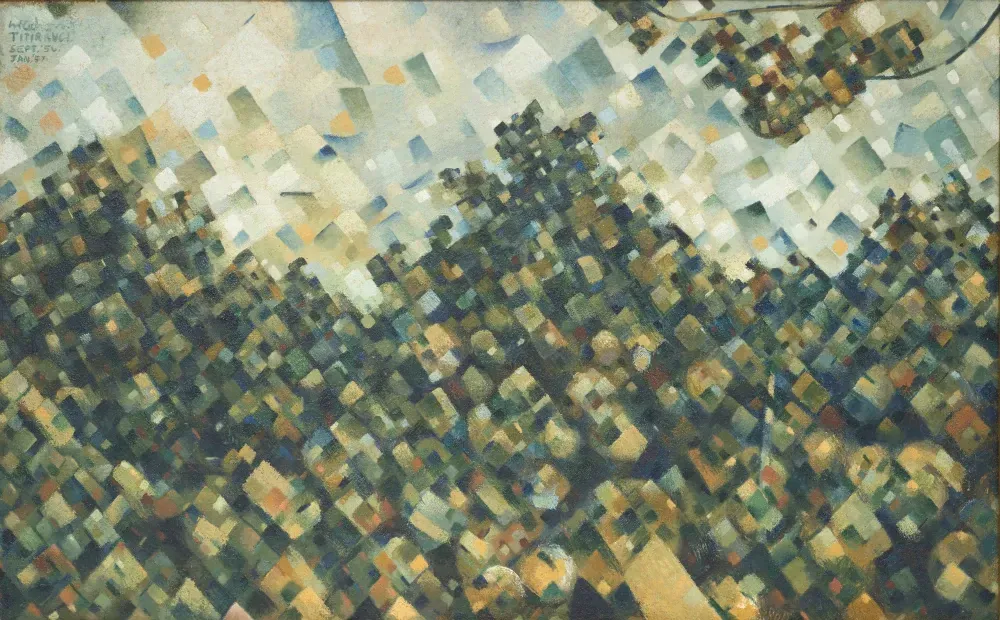

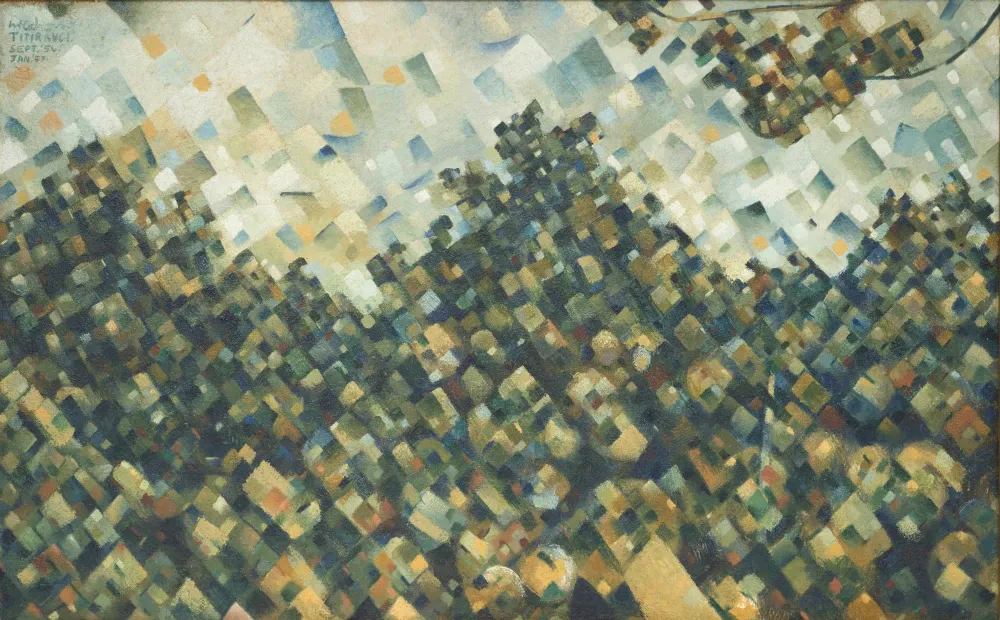

Colin McCahon - Titirangi, 1956-57. Supplied.

The rooms and places

The first room captures the bold colours and strong forms that were equally inspired by Modrian as the light dancing across French Bay in Titirangi - McCahon’s home in the 1950s. During this period, some of his works obtusely referenced Modernist painters. In the elegantly stark Here I give thanks to Mondrian, McCahon notes that it “belongs to a whole lot of paintings that were - believe it or not - based on the landscape I saw through the bedroom window.” With its balancing act between the physical and trascendental, this work acts as the perfect segue into the 1960s.

The second room is filled with the sprawling works of the 1960s that owe themselves to both the hours McCahon spent teaching at the University of Auckland Elam Art School, his shift into the working class suburb Grey Lynn and the establishment of Vatican II. Considered a turning point in Catholicism, the intent of Vatican II was to bring the church into the 20th century, including aesthetically.

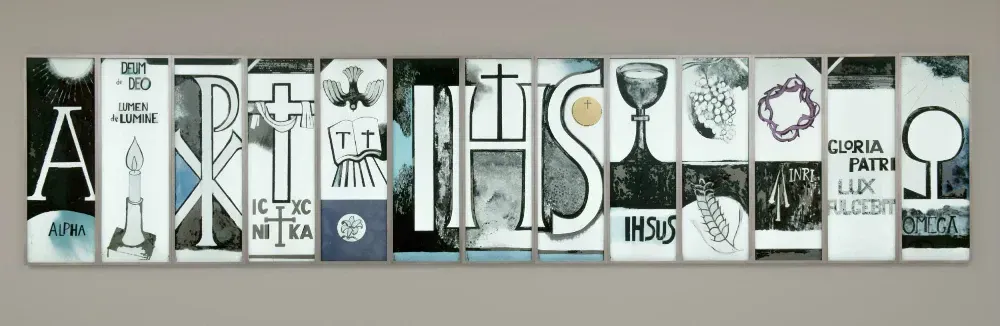

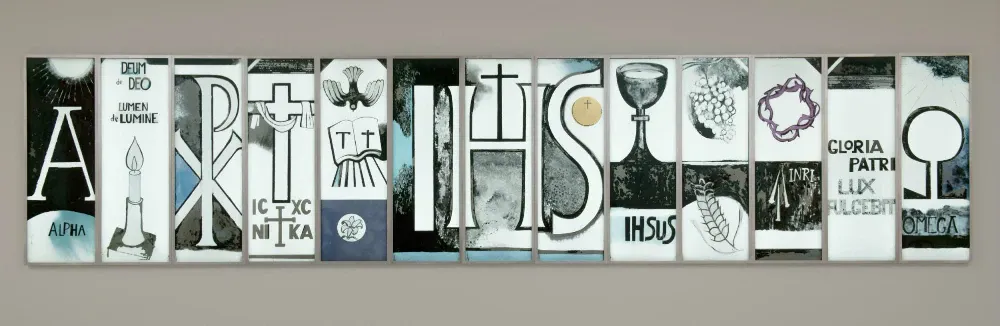

This is best captured in the exhibitions indisputable piece de resistance. For the first time ever, The East window Convent Chapel of the Sisters of Our Lady of the Missions is on display to the public after being commissioned for a private chapel. The first religious commission in Auckland after Vatican II, the merging of biblical stories with McCahon’s modernist style questioned how to think about spirituality in this new era. As to be expected with McCahon, it is richly iconographic. Intended to be viewed from left to right, the work goes from dark to light, from sinner to saved. Rather than concerning himself with the earthly realm, this work focuses on the clouds; it is easy to imagine them perpetually shifting across the windows.

Colin McCahon - East Window, 1965-1967. Supplied.

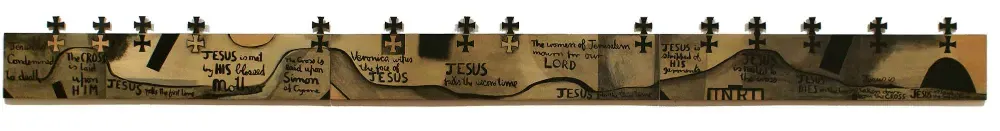

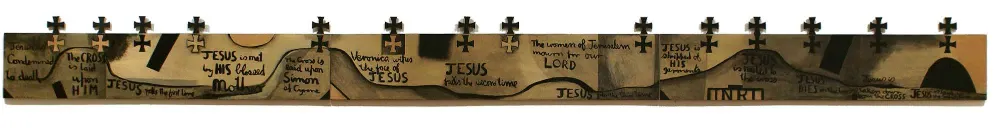

Across from it is The Way of the Cross. Here, the last day of Christ takes place not in Jerusalem but in Tamaki Makaurau, elegantly colliding an earthy spirituality with the shock of the new. These transcendental themes are brought firmly back into the physical realm courtesy of Landscape Themes and Variations (series A). This vast piece manages to feel raw, yet pastoral a deeply personal yet communal experience. As a whole, this room captures a pithy EC Simpson quip, describing McCahon’s style as “an audacious and original vision in a tradition as old as religion itself.”

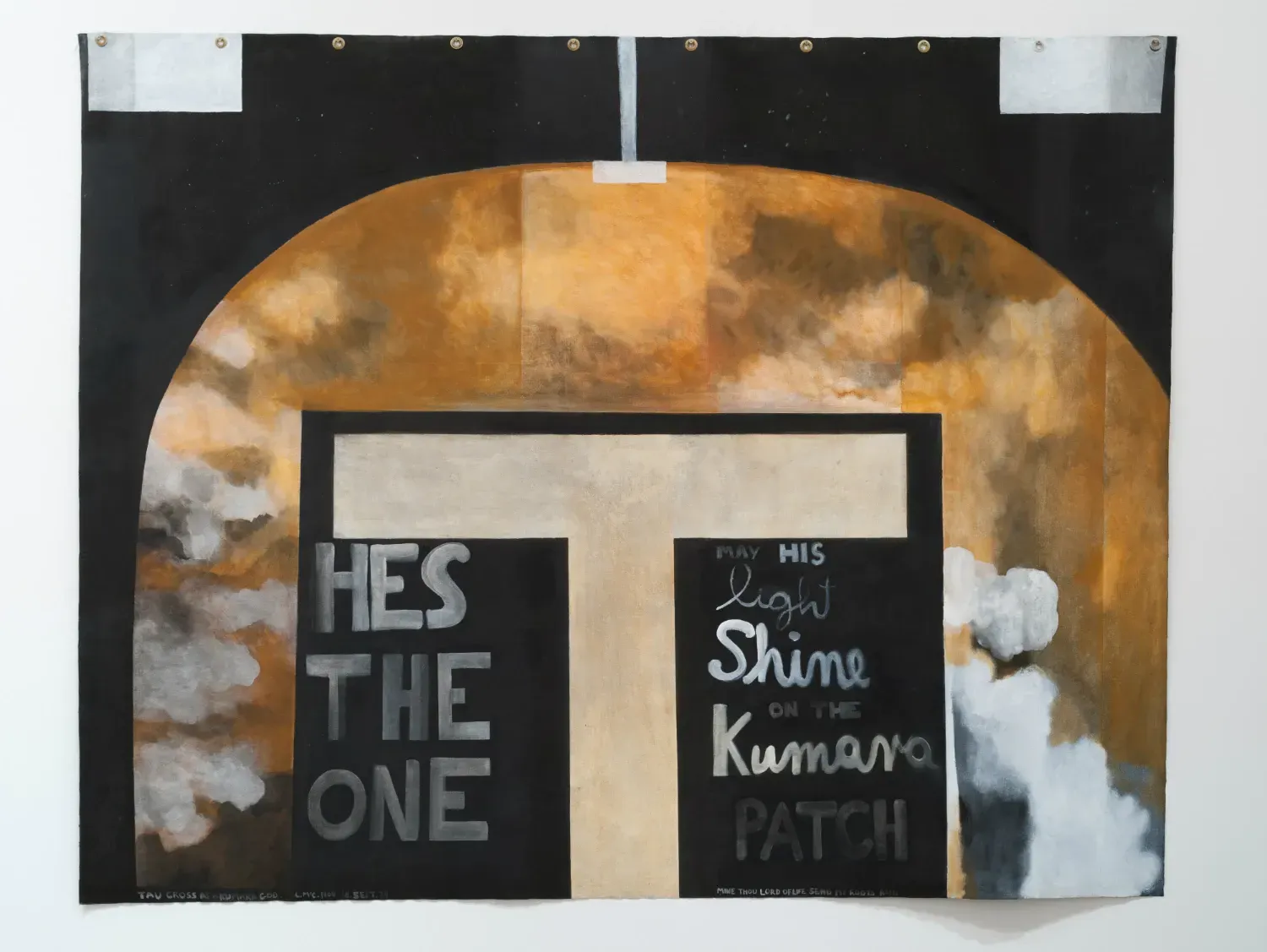

Colin McCahon - The Way of the Cross, 1966. Supplied.

The final room captures the 1970s. McCahon entered this decade with a new painting studio at Muriwai Beach which allowed him to paint vast canvases where the natural and spiritual worlds found in the previous rooms collide in a crisis of faith. Walking into this space, the shadows of these works may weigh a tonne, but that only makes them easier to fall into. Here, we see an artist at his peak, capturing New Zealand’s darkness with ease.

A Place to Paint: Colin McCahon in Auckland has a strong focus, with clear, keen curation and well-written wall text that gives gravitas without being gushing

Celebration and retrospective

A Place to Paint: Colin McCahon in Auckland has a strong focus, with clear, keen curation and well-written wall text that gives gravitas without being gushing. In many ways, it is a wonderful exhibition that succinctly captures McCahon’s impact with no filler and is a real pleasure to walk through. However, it leaves some questions unexplored. For example, with a legacy built on matters of faith, identity, and cultural collision, what does McCahon’s work mean in a multicultural, secular Auckland? Which ideas of his retain their impact today, and which lose power out of their historical and artistic context? A Place to Paint achieves its tasks as celebration and retrospective admirably, but I would have liked to see at least some hints at the contemporary impact of a figure who looms so large over New Zealand art’s past.

Having said that, this is truly worthwhile exhibition that highlights the skill of the curators of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki and showcases some of the finest work from one of New Zealand’s most esteemed painters.

A Place to Paint: Colin McCahon in Auckland runs until January 27, 2020. Visit Aucklandartgallery.com