Confronting the "Incredibly Effective" Destruction of Creativity

Ladies and gentlemen of the jury - we must confront a crime that cannot be swept under the carpet any longer.

We know that Aotearoa schools are killing creativity. The evidence is overwhelming.

Recent research by the Centre for the Arts and Social Transformation at the University of Auckland published in the report Te Rito Toi: The Twice Born Seed details the manner in which the murder has taken place. A forensic examination of the crime, the report details how the narrow focusing on literacy and numeracy in Primary schools, the almost complete lack of arts in Initial Teacher Education, and a poverty of resourcing in the arts in schools are primary suspects of the silent but incredibly effective destruction.

Three years ago, with a Prime Minister as the Minister for the Arts and the promise of transforming our schooling system on the scale of the reforms of the first Labour government, some of us in the arts dared to dream for a while. We hoped we would lose the sterility and barren ideas that had dominated schooling for so long. But nothing meaningful has changed for the arts.

Action, not words

The Ministry of Education has had more than 20 different reviews of schooling. Not one made any reference or gave any thought to the power of the arts and creativity to make the difference we so desperately need.

Instead, the promise of reform has been replaced with tinkering around the edges, avoiding the difficult remedies suggested in the Tomorrow’s Schools Report, and deciding to refresh the curriculum rather than reform it.

To add insult to injury, the Ministry has decided to introduce more literacy testing, and to delay refreshing the arts curriculum for another three years. At that point, perhaps the old VHS copies of how to teach drama might be replaced with something new. Maybe there will be some fresh ways to teach Pasifika art to replace what was produced a generation ago.

Professor Peter O'Connor. Photo: Andrew Lau Photography.

The Ministry has, one can only imagine, deliberately ignored the overwhelming evidence that the arts make a powerful difference to the wider curriculum, and especially to literacy and numeracy. We know drama helps children read with a deeper capacity for inferential understanding, that dance helps children understand the patterns and rhythms of numbers.

The visual arts help us understand spatial relationships so we might better understand personal relationships, and music salves the soul in a way that nothing else can. Imagine if, as they designed the New Zealand History curriculum, consideration was given to how the arts might bring that alive in classrooms.

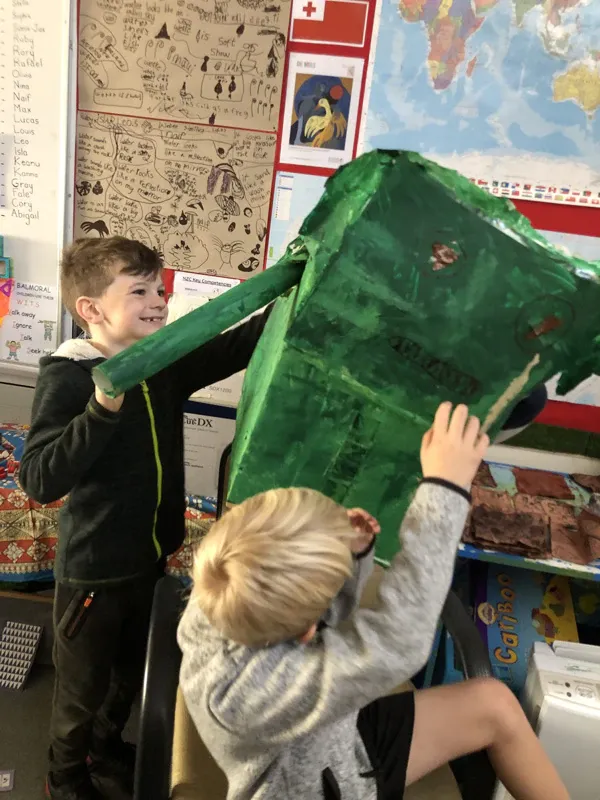

Balmoral School students working on The Giant Who Threw Tantrums, part of the Te Rito Tio: The Twice Born Seed curriculum. Photo: Supplied.

The World Health Organisation report on the arts and wellbeing released in 2020 synthesises over 7000 studies on the importance of the arts and details the difference it can make in young people’s lives has been simply ignored. The Prime Minister in 2019 spoke of craving a time when the word ‘wellbeing’ was used, we would immediately think of the arts. Maybe she might whisper that idea to someone in the Ministry of Education.

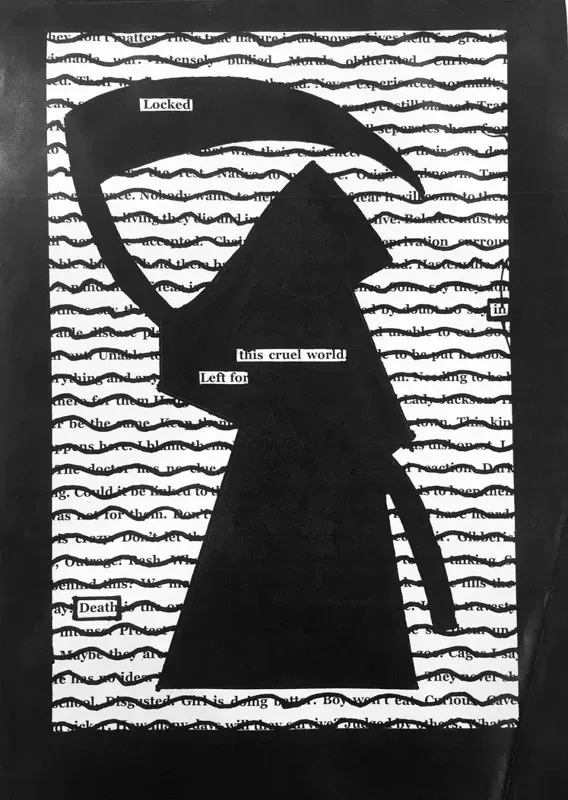

The research report suggests that the death of the arts in schools means other things wilt and die. Curiosity, the ability to live with and transform ambiguity, to play with ideas and others to see things differently fades away in our schools too.

The joy of learning becomes instead a race for qualifications. The impacts of these deaths are writ large in the report too.

Learning from the past

The reforms of the First Labour government were based on the notions that education is a public good, a national treasure, that acts as a bulwark against extremism - a way for not only lifting individuals out of poverty but also ensuring a flourishing democracy. Clarence Beeby and Peter Fraser built the system on the pioneering thinking of John Dewey.

Dewey wrote extensively on the cultivation of the imagination through the visual arts, music and drama. He suggested that education in the arts is not about training children simply in aesthetic appreciation or understanding, but is about creating citizens who hold a belief in the potential of the imagination.

Beeby understood too, that this was not just about imagining individual achievement but it was about building the social imagination; a way of thinking about possibilities for a more just, equitable and fairer world. He saw creative education, founded in the arts, was the central plank in how schools might not just replicate the social order but be part of changing it.

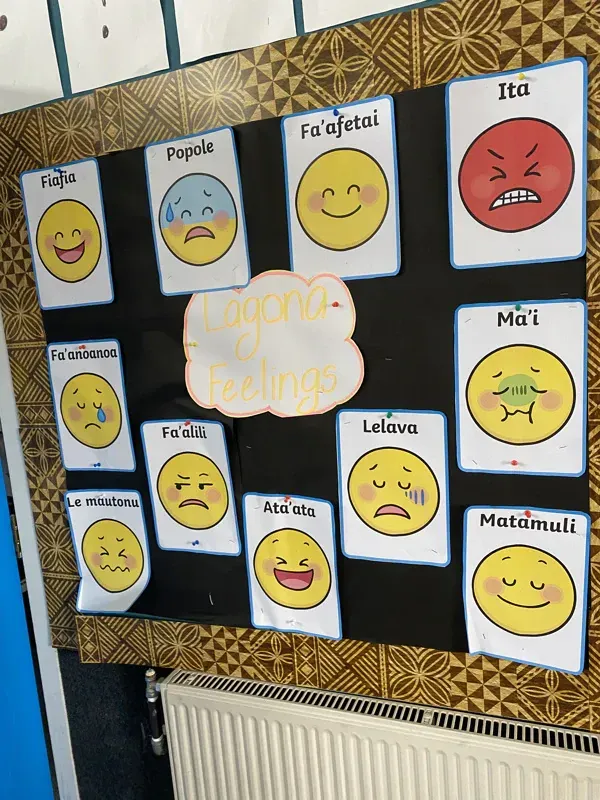

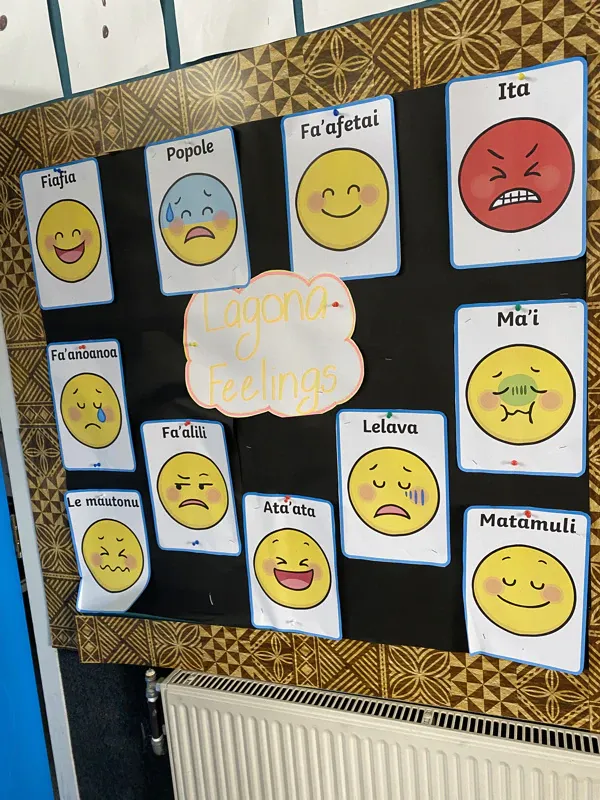

Wiri Central School using Te Rito Toi, The Twice Born Seed materials to encourage understanding of emotions. Photo: Supplied.

The true measure of public education is not in individual achievement, but in the success of participatory democracy. What we risk with the current schooling is creating classes of people disconnected from a sense that they are able to be active participants in their own lives. The dangers of such an approach is obvious as new nationalisms and dehumanising ideologies find fertile ground in collapsing economies.

The Centre for Arts and Social Transformation at the University of Auckland in partnership with the NZ Principals’ Federation and NZEI are calling for resurrecting the arts in New Zealand schools as a matter of urgency. The second public panel on the arts in education, Te Rito Toi, The Twice Born Seed will be held at the National Library in Wellington on 21 April at 5.30pm.