Cushla Donaldson explores progressive politics as cultural commodity

Written by

A conundrum

Outside the Audio Foundation, K Rd is humming in the sunlight. Inside, the room is slightly chaotic. Previously, I’d only ever been to gigs there, all at night. There’s tons of amps and guitars piled on top of a grand piano. An audio display of taonga puoro shrills from the next room.

Cushla Donaldson and I are discussing the relationships between aesthetics, politics and patronage. Her recent installation at Melbourne Art Fair - called 501s - caught the mainstream media’s attention for the barriers it broke in these perilous spaces.

And they are perilous. “At times I’ve had the opportunity to compromise in various ways. But I have largely chosen not to.” Compromise? “Often it’s being asked to be less critical of context.”

Donaldson talks with a formal accuracy, but also, with the force and passion of deep conviction.

All her work is politically charged, in many ways. I’m interested in how that works, from both a critical perspective and a professional one. How does politically volatile work sit within the art market? Does it present barriers? Opportunities?

Donaldson laughs. “It’s not the easy way. However, one thing that people probably do know about me and my practice is that a certain standard of ethical artistic behaviour is important to me and the work as it exists in this fragile political climate.”

“At times I’ve had the opportunity to compromise in various ways. But I have largely chosen not to.”

Platforming the subject

Donaldson has gone to great lengths to channel her subjects directly into the work on display, in ways that are both innovative and powerful.

For instance, in 2015 she won the Lexus Premiere Award within the Sculpture On The Gulf exhibition on Waiheke Island. Her winning of the award was met with some controversy, as was the work itself: The Precariats, named after the sociological term for the growing numbers of people in low paid, insecure employment.

“I’m interested in how money operates in art. And I’m intrigued by old and new forms of patronage” she explains. “I thought it would be interesting to do a crowdfunding exercise where the patrons could collectively and openly direct the form of the work. So they donated funds and I represented their requests, logos and various items on the structure of the work. There was criticism by some of that handing over of artistic control, however it is not uncommon, this mediation, just overt in this work. And that’s how it worked: open source aesthetics. Some people - especially more conservative viewers - thought it looked messy.”

Sculpture on the Gulf could be described as economically complex. It’s free to attend, but the $40 ferry ride may put it beyond the reach of some Auckland families. Once there, visitors are as likely to be dazzled by the spectacular real estate, as by the views, or even the art. And - not unreasonably - the art itself tends towards the snazzy: there’s a strong sense of grand elegance. As with many sculpture gardens, disruption tends to be about the visual landscape, rather than those who might - or might not - populate it.

Inserting a piece that contrasts and complicates this experience was no accident. “I have always been interested in looking at how authority structures operate and critiquing them. So right from the outset - from art school - I was doing that, and I have support, both artistic and financial, but I am aware that there are some who are threatened by my kind of critical investigations.”

Patrons and collectors

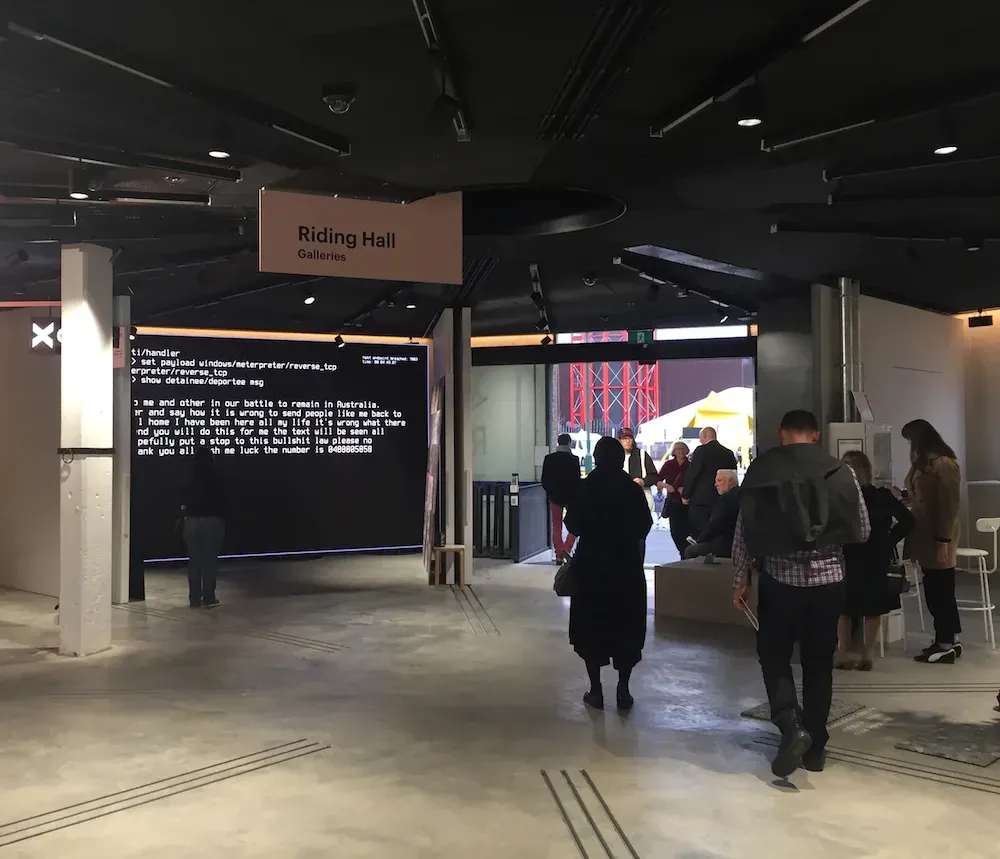

Arts patronage is intrinsically subjective: people pay for what they like and for its current and future cultural currency and the ideas they want to align themselves with and support, from patrons to collectors to funding agencies. By prioritising both the identity and the requests of the donors in The Precariats, Donaldson addressed this situation head on. Recently, she both extended and inverted this idea in a video installation - at the Melbourne Art Fair - called 501s.

Section 501 of the Australian Immigration Act gives the Australian Minister of Immigration extensive discretionary power to either deport or detain anyone who “fails” a character test (mostly, but not solely, defined by previous custodial sentences). The Act explicitly exempts the minister from any requirements of natural justice in exercising S501. The results are the much publicised human rights abuses in Australian detention centres, involving many New Zealanders.

When the curator Jamie Hanton of Christchurch gallery The Physics Room invited Donaldson to produce an installation at the Melbourne Art Fair, these systematic, ongoing, state-sanctioned injustices seemed like fitting and timely subject matter, enabling Donaldson as a New Zealand artist to represent the abuse - and the abused - in a highly commercial art environment, within the country perpetuating it.

On this work Donaldson collaborated with advocacy group Iwi in Aus and AUT policy analyst Dr. David Hall. Hall points out to me that S501 is so open-ended that “you can detain who you like, without reason.” Hall further points out that Australia has a long history in penal injustice, dating back to its very origins.

He quotes the child psychoanalyst Selma Fraiberg: “Trauma demands repetition.” While the cyclic perpetuation of injustice is now well understood, perpetrators’ strategies have been less well explained. Fraiberg has identified how perpetrators of violent injustice often adopt an attitude of moral superiority, enabling them to disavow their actions, even while perpetuating it. One example is the reluctance of Australian politicians to apologise to Aboriginal groups for the harms wracked by policies like forced assimilation. It eventually came in 2008 - amid much anguish - from Labor Prime Minister Kevin Rudd.

Such self-proclaimed superiority may be one way of describing Peter Dutton, an archly conservative Brisbanian MP who led a small boycott of Rudd’s famous apology. And as immigration minister in 2014, Dutton was the architect and executor of the maltreatment of former prisoners under S501.

The challenge was to find a way to talk about the problem in a way that did more than talk about the problem. If The Precariats provided a platform for its own crowdfunders’ identities and aesthetic preferences, how might 501s do the same thing for the innocent people held in Australian detention centers?

The solution - again - was technological. Donaldson designed a video installation consisting of two main elements. One element was a 3D animated sequence, a digital depiction of coded luxury: champagne pouring into an elaborate glass slipper. In addition to the Cinderella reference, the champagne in the shoe parodies an historical marketing stunt, staged by “The Grande Dame of Champagne”, Madame Veuve Clicquot.

“She did a promotion of her champagne that she’d relaunched after her husband died. She invented the orange label and did this event where she made a giant glass slipper in Venice and filled it with champagne. She was a kind of proto ‘lean-in’ capitalist feminist.”

Donaldson is critical of the lean-in movement’s preference for making gender inequality a problem that women can solve by reframing their own ambitions. “It’s deeply concerning. Feminist capitalists are not actually feminists, and are socially dangerous. They can be the gatekeepers, standing watch against real social change. Their actions often uphold the patriarchy they supposedly stand against.”

“The detention centre was worse than any prison I’ve ever visited. There’s eight people to a very small room.”

The second element consists of text messages sent - live and direct at the time of the art fair - from inmates held in the detention centers. Donaldson developed a system by which the texts could be received and substituted into the frame that previously showed the glass slipper.

In an interesting twist, just weeks before the fair, the then immigration minister Dutton attempted to deny detainees the right to possess a cell phone. His case was eventually thrown out by the High Court of Australia. This established the legal right for detainees to possess phones, which was a technical criterion for the show to work.

Donaldson visited a centre in Melbourne as part of her research for the project. She described it as “heartbreaking. The detention centre was worse than any prison I’ve ever visited. There’s eight people to a very small room. Bunks. They’re never alone. They have no space where they’re alone. There’s no natural light. It’s very wrong.”

At one point, I talk up the positive outcome of giving these people a voice. But Donaldson is quick to correct me. “No” she says. “A platform. They already have voices.” We talk further on the ethics of representation. “The main area we need to look at it is participatory parity. How are we going to get to a place that allows everyone to participate equally within culture and society? That is the focus of my practice at the moment.”

Representation is vital in this practice. Donaldson refers to Nancy Fraser, a theorist who discusses the barriers to ‘participatory parity’, among which is political and cultural representation. For Donaldson this is key, and - more often than not within the arts - handled clumsily, at best.

“The aesthetics of care are often not critiqued effectively in art. I’m interested in what ‘radical care’ looks like.”

Even as Donaldson deploys subject-created content, she insists on robust self-critique within her own role as the facilitating artist. “The aesthetics of care are often not critiqued effectively in art. I’m interested in what ‘radical care’ looks like.”

What was the response to 501s for the detainees who populated it with their messages? “Amazing. That it brought them together as a community. That it was important to have a project that highlighted them because they thought no-one cared. That it was cool to see each other’s texts. That the activity itself was bonding.” Preparations are now underway for a restaging of the work, and Donaldson continues her research into the “fascisms that are occurring, not just overseas, but right next door and in our own country. It's so important to take care of people who have been forcibly removed from participating in a society and culture.”

All images of her works courtesy of the artist: installation views of 501s, Melbourne Art Fair, 2018, and The Precariats, Sculpture on the Shore, 2015.

Portait of Cushla by Raymond Sagapolutele.

You can find more out more about Cushla's work on her website www.cushladonaldson.com