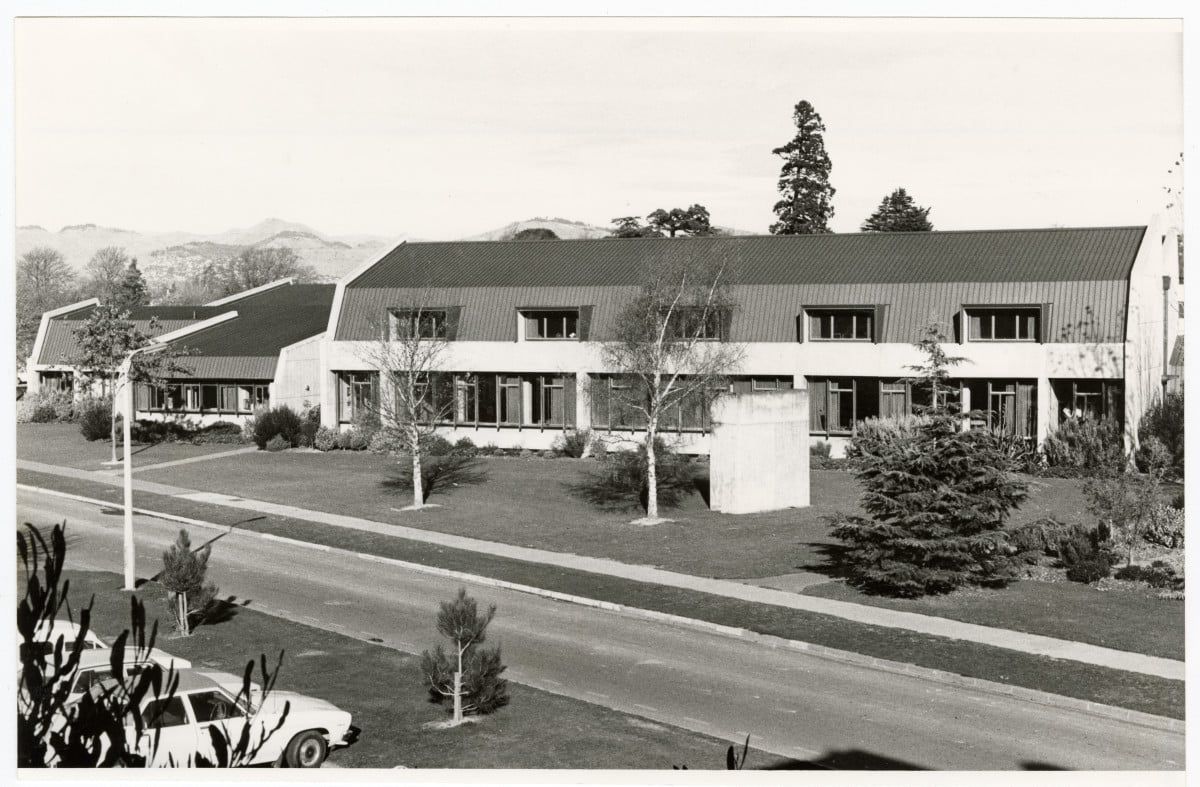

For-and-about: The National Grid’s school years

Luke Wood, original founder of the revived graphic design journal, traces the publication’s evolution from a historical anomaly – the graphic design department at Ilam late last century.

Image: The National Grid issues #1–8 front covers, 2006–2012.

This is the first instalment of a new monthly column from The National Grid, a graphic design journal based in Aotearoa currently edited by Luke Wood, Matt Galloway, and Katie Kerr.

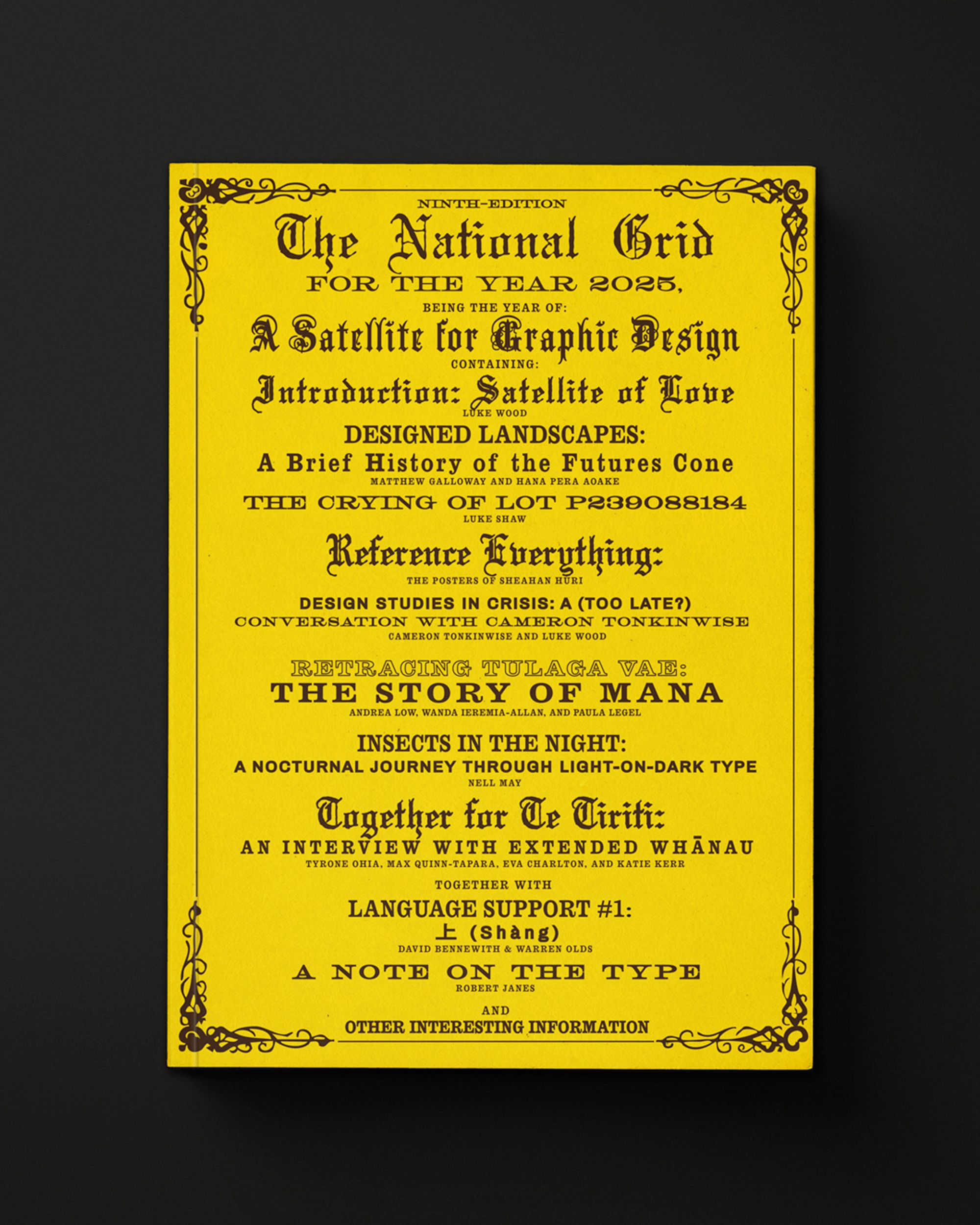

The National Grid was a graphic design journal that I published in collaboration with a friend and colleague, Jonty Valentine, in a run of eight issues from 2006 until 2012. More recently however – a good thirteen years later – this publication has been revived, and by the time you read this issue #9 will be hot off the press. As they say.

I’ve already written about the decision to restart The National Grid in the introduction to the new issue which you can read on our website. Now, I want to articulate why Jonty and I started the project in the first place, by tracing the publication’s evolution from a historical anomaly that is the graphic design department at the University of Canterbury’s School of Fine Arts, colloquially known as Ilam. Jonty Valentine and I were both students there in the early 1990s.

Graphic design was first offered as a subject at Ilam in 1962 under the direction of Maurice Askew, a then new appointment to the school who had come from working at the Granada Television Studios in London. Maurice’s appointment signaled the school’s move away from the Arts & Crafts Movement and towards the then more up-to-date attitudes and aesthetics of European modernism. His, what we would now call, multi-disciplinary background in television led to his introducing film, animation, and photography to the school’s curriculum.

By 1973 a younger British émigré, Max Hailstone, was employed to take over the graphic design program, while Maurice ran the new Film department. Max then ran the course, which he retitled Typo-Graphic Design, for the next twenty-four years, until January 1997 when he was tragically killed in a car accident while on a teaching exchange in the United States.

Jonty Valentine and I were both taught by Max. I was in the last class to graduate under him, completing my undergraduate studies in 1996. Jonty and I had different experiences of, and hence perspectives on, Max’s teaching. And, in hindsight, I have come to see The National Grid as a project through which Jonty and I were negotiating these different experiences and perspectives. Often our conversations turned to our educational experiences at Ilam.

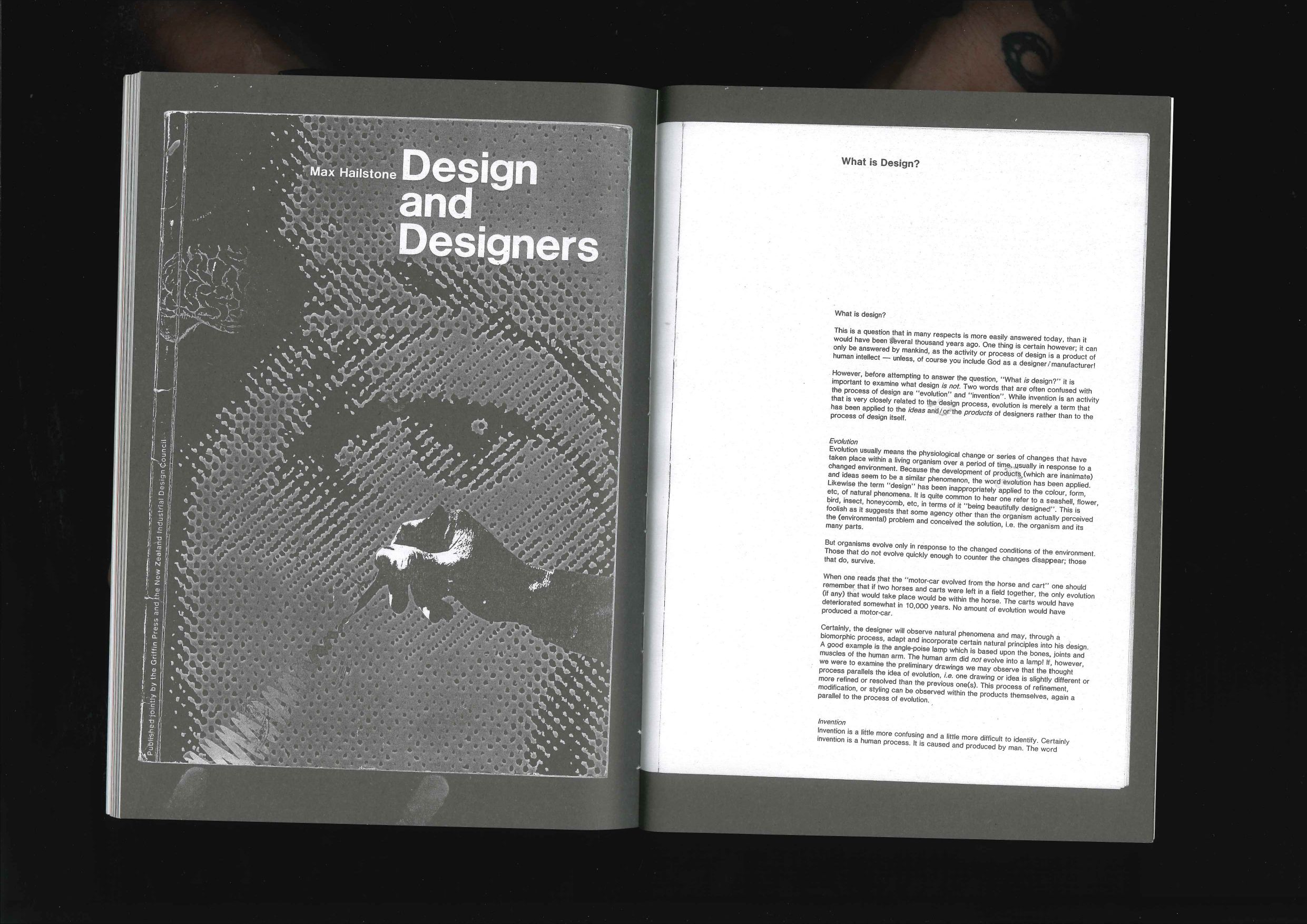

reproduced in The National Grid issue #1, 2006.

Issue #1 of The National Grid reproduced – literally photocopied – a section of the introduction to Max’s 1985 book Design and Designers. A book both Jonty and I had copies of, and one we would return to regularly to either confirm or contradict things we thought we remembered from half forgotten, and probably quite vague anyway, classes with Max from over a decade ago.

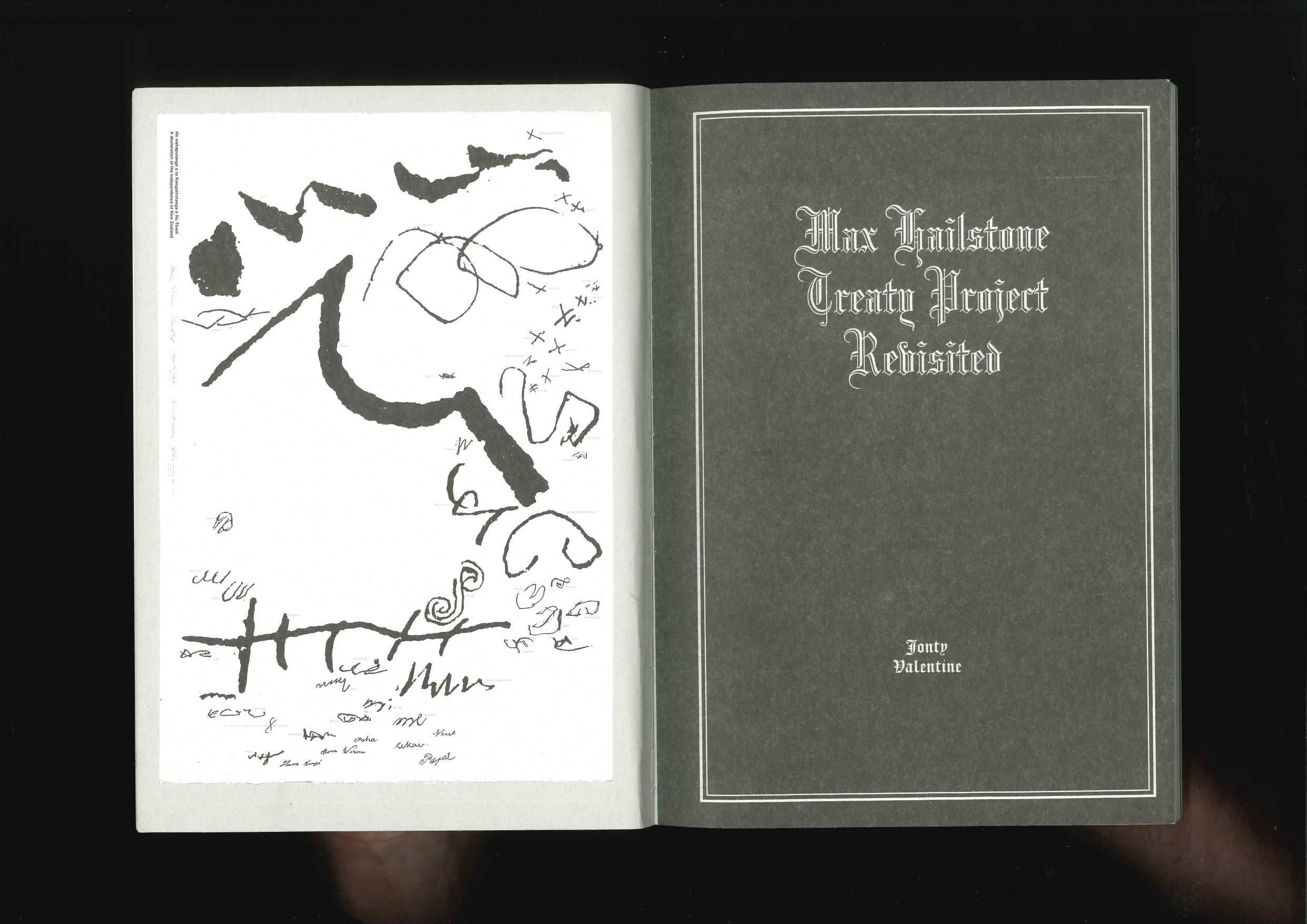

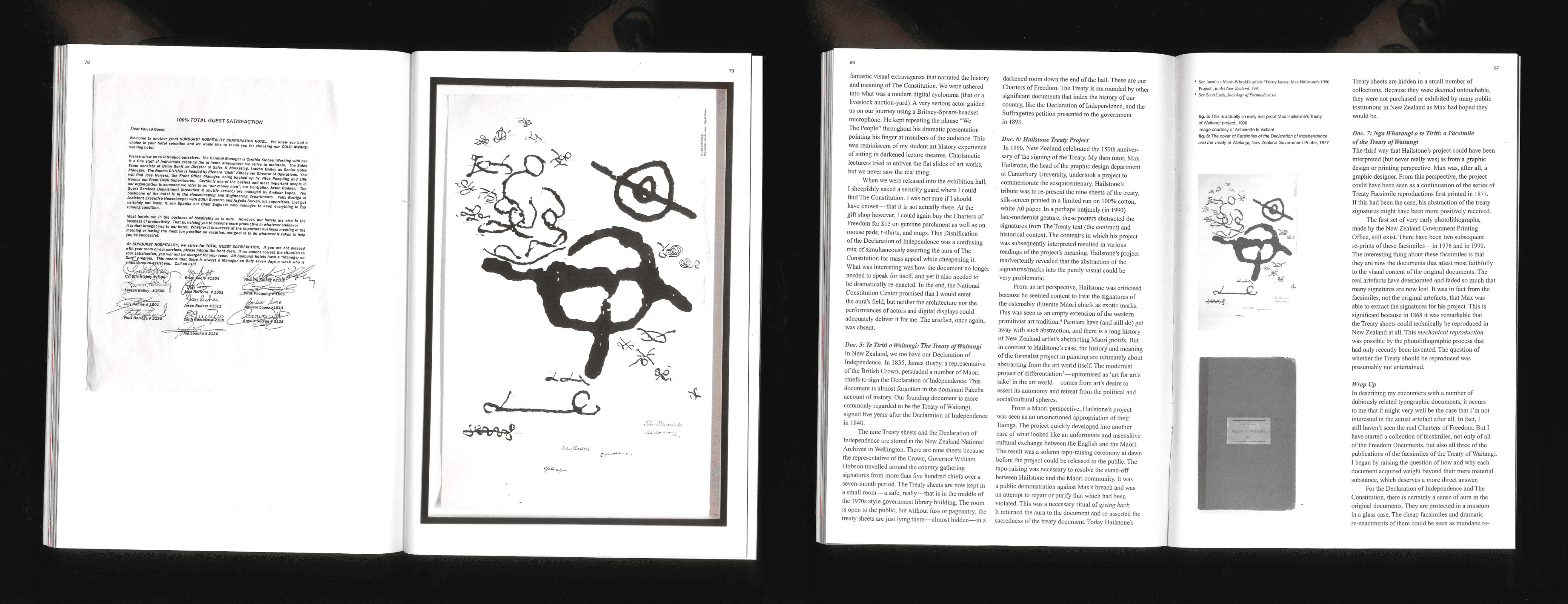

Max is, perhaps unfortunately, most well-known these days for his infamous 1990 project in which he reproduced signatures from the Treaty of Waitangi as large-scale screenprints, removing these marks from their original context and redeploying them as formal compositional devices. This is a project that Jonty has written about twice in The National Grid, and isn’t one I will go into in depth here, except to say that Max had not consulted or worked with Māori at any point, and the project was so controversial that it required a tapu-raising ceremony held at Ilam in September 1990. The project has, quite rightly, been criticised and lampooned ever since.

This project is evidence of Max’s being a bit out-of-date at the time, and very much English. His practice, even by the 1990s, was still that of a mid-century European modernist tradition. One wherein so-called "primitive art" was sometimes fetishized and superficially appropriated, albeit via an abiding and often sincere interest in alternate histories of visual language.

This project also illustrates that, while Max certainly went about doing this work the wrong way, the fact he was interested in doing it at all is significant. Jonty has claimed this as a rare example of practice-based research in graphic design in Aotearoa. If we can put the obvious faux pas aside for just a moment, this project can be seen as the work of someone interested in design practice as a way of looking at, thinking about, and processing culture. Something that was a bit unusual at the time.

By the time Jonty and I were studying graphic design at Ilam, other tertiary institutions were rebranding courses in graphic design as Visual Communication or Communication Design. This rebranding was an attempt to make graphic design sound less arty, and align it more clearly as a tool for business. By the late 1980s neoliberalism was in, and design was generally perceived to be primarily for-and-about business and commerce.

Except at our school where, under Max Hailstone, design was still primarily for-and-about culture and society.

I never thought about it at the time, but it seems significant to me now that Max was born in England in 1942, at the height of the Second World War. Max grew up, discovered, learned and practiced design, then still a relatively new profession, in a specifically post-war context. One in which design had a very real role to play, not just in the rebuilding of cities and infrastructure, but in the reimagining of post-war life.

For Max, I think, design work was social work. And students of design should be as engaged with culture and society as they were with setting good type. I recently rediscovered the original course outline that Max handed out to my class in 1992:

“… it is important that the subject is seen in a wide context rather than in isolation. Too often the subject is taught for the sake of itself with very little self-criticism or sense of responsibility in the wider order of things.”

Our abilities to exhibit contextual awareness in critiques was important, and the fact we had to take liberal arts papers alongside our studio-based courses was critical to Max’s approach to a design education. An approach that set up in his students (some of us at least) attitudes and ambitions that went well beyond the expectations and requirements of the industry at the time.

The National Grid announced itself, on the spine of the very first issue, as a “peripheral publication for graphic design”. The centre we felt peripheral to, was the national design industry. The National Grid from its inception was to be firmly anti-establishment in this regard. Jonty and I went through Ilam at different times, but met in the late 1990s and bonded over our disenchantment with the industry we had ended up in.

In a concerted effort to find work we considered interesting, both Jonty and I had spent a good part of our careers leading up to The National Grid designing books for museums and art galleries. As a result we ended up, almost accidentally, reading a decent amount of contemporary art writing – writing that was often critical, analytical, interrogative, and grounded in historical precedents. This reading reinforced for us how superficial and self-congratulatory design writing in New Zealand tended to be. Inevitably we wondered why we couldn’t find similarly engaging critical discourses about design in the country we were living and working in. Naively, we started to think maybe we could do something about that.

in The National Grid issue #1, 2006.

Our editorial for issue #1 reads as a manifesto of sorts. One that attempted to quickly sketch our disenchantment with our immediate context, but also, on the other hand, to more optimistically suggest what we might look at, write about, and represent instead. The National Grid, in this sense, became a project through which Jonty and I would then aim to dig up examples of the kinds of projects, practices, discourses and histories we felt were missing from the industry-centric representation of design.

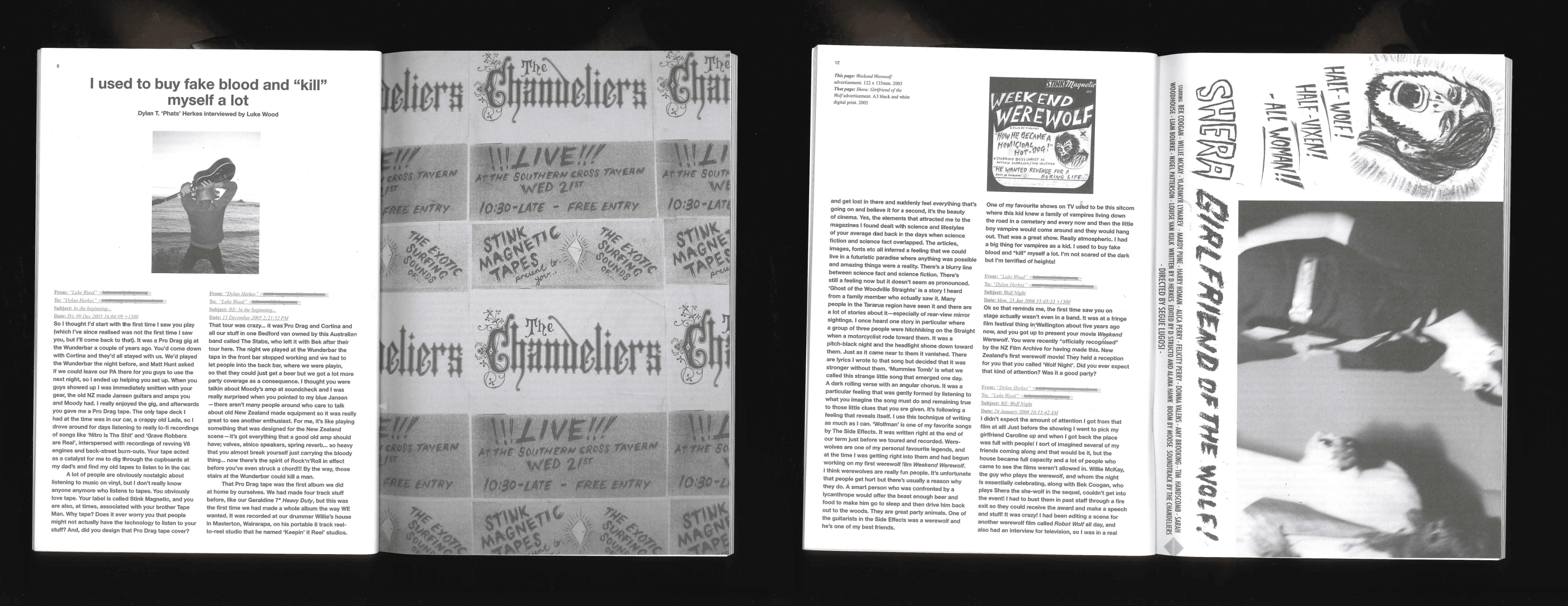

Dylan T. ‘Phats’ Herkes interviewed by Luke Wood in The National Grid issue #1, 2006.

For example, I was interested in profiling people who I thought were great designers but would never end up in the annual design awards because their work wasn’t primarily commercial. For our first issue I interviewed Dylan Herkes Tekai, then a young Maori musician and self-taught designer who ran a very small record label and toured local bands around the country. He also designed all the cover art and posters for these bands, and I had become totally smitten by his work.

Also in issue #1 Jonty wrote his first piece to touch on Max Hailstone’s problematic Treaty posters. In The Weight of a Document Jonty wrote his way through various contracts and their reproductions. From the American Declaration of Independence to our own Treaty of Waitangi, Jonty began to frame these types of official documents as important parts of an understanding of graphic design history.

These approaches largely set the tone and approach for the next seven issues, and through our own research as well as working with as many other people as we could, we tried our best to uncover hidden, forgotten, ignored, and supposedly unimportant design stories to help build an alternative narrative around the historical trajectory and contemporary practice of graphic design in Aotearoa.

in reference to the first edition of Wisden Cricketers’ Almanac (John Wisden and Co., 1864).

The National Grid came to an end in 2012 with issue #8 – mostly due to workload, lack of institutional support, and difficulty getting paid by small independent bookstores around the world. The printing of the first two issues had been paid for by the Ilam School of Fine Arts Harkness Fund in 2005. Without that support this project probably wouldn’t have seen the light of day. The same funding has made it possible for us to restart the project this year.

Over the years that followed, I came to really miss the conversations and specific thinking about graphic design that working on The National Grid had required of me. And so, a couple of years ago now, I started reaching out to various people who might want to do something like this again. While I had something more like a research group on my mind at the time, conversations with Katie Kerr and Matthew Galloway quickly turned towards picking up where Jonty and I had left off with The National Grid.

Now, we are about to launch issue #9. In many respects it will probably just look like we’re carrying on, again. Business as usual. But it does feel quite different to me now. In part, no doubt, because Jonty hasn’t been able to be on board for this issue. As a result, I don’t think Max Hailstone’s ghost was in the room. Both Katie and Matt are graduates of the graphic design program at Ilam, but they weren’t Max’s students – they were mine.

When I came back to teach at Ilam I wasn’t at all interested in reproducing what Max had been doing. I didn’t actually get on that well with Max, and formally we were interested in very different things. He once told me that band posters weren’t “real graphic design,” and he lost me then. But it is interesting now to understand that, aesthetics aside, I’m still fundamentally coming from the same place Max was. A place where design is first and foremost for-and-about culture and society. And that’s the place The National Grid will always be coming from too.

Issue #9 launch parties

Tāmaki Makaurau – Monday 10 November, Objectspace

Ōtautahi Christchurch – Thursday 13 November, Sir Miles Warren Gallery