Going Global: Simon Denny

Written by

Berlin has long held a reputation as being a city where artists can live, work and party on very little money. Every so often, rumours fly that another city is “the new Berlin”, but still, Berlin perseveres as the city of choice for artists who want the freedom of time, space and money to focus on their art.

New Zealand artist Simon Denny has been living in Berlin for 10 years, and says it remains one of the more visible art centres of Europe.

Just last month, Apollo magazine named Denny on their list of 40 Under 40 inspirational young people in the European art world. It’s a recognition that will come as no surprise to those with even a vague knowledge of his work. He represented New Zealand at the 56th Venice Biennale, and has had solo exhibitions at MoMA PS1 (New York), Serpentine Gallery (London) and Te Papa.

Denny’s practice looks at technological advances and the culture around people who make technology, more recently exploring the work of key figures of the digital age such as Edward Snowden, Kim Dotcom and Peter Thiel.

His 2017 exhibition ‘The Founder’s Paradox’ reinterpreted classic board games to examine competing ideas for New Zealand’s future. One of those ideas was the vision of the country as a libertarian haven, as exemplified by US billionaire Thiel’s New Zealand citizenship.

The Silicon Valley mogul caused a stir when he visited the exhibition unannounced while he was in the country on other matters.

The artist had a chance to sit down with him earlier this year and Denny says their conversation will inform a revised version of the exhibition that will open at the Christchurch Art Gallery in December.

“One thing I was amazed by was he said my research was pretty accurate and he was quite amazed by the detail that was in it. “

“I don’t have to tweak the narrative [for the revised show] so to speak because it was mapping onto what I imagined was really happening, but it certainly might put emphasis on certain things and maybe add a few things.”

He says the meeting was a one-off purely to discuss the work.

“We talked a bit about [‘The Founder’s Paradox’] and… basically I asked him a lot of questions, because I’d done a lot of research independently through secondary resources like articles and tweets and whatever, Medium think-pieces... to fact check a little bit was pretty interesting.

“He also said he thought my depiction of cyber-libertarianism was a little dark, which makes sense,” Denny laughs.

The cultural impact of media and technology has been the focus of Denny’s work since he moved to Frankfurt for his MFA at Städelschule.

“It was 2007 when I [moved] and that was a big moment in what was happening with personal computing and the internet. The iPhone was born, and having just moved, I didn’t move with much but I did move with a laptop. I’d just gotten a laptop for the first time and I just started to use social media really properly. That all seemed to be very important,” he says.

“Also at the school it was all being discussed among peers of mine, like what was this stuff, what is Google doing, what is Facebook doing, what is Apple doing? That was a thing that came up a lot socially.”

Art making is a social thing, one that is informed by the environment in which it is created, Denny says.

Art making is a social thing, one that is informed by the environment in which it is created.

“As an artist I always feel like I’m trying to do something in a context and if the context changes and your dialogue changes and the culture in which you’re participating in changes then the work also changes. And that was definitely the case for me, it was a moment of re-assessment of what I was doing.”

Denny moved to Berlin in 2009, after graduation, and following a short stint in Cologne. Most of his friends from art school moved to Berlin because it was an affordable place to live with a thriving art community. At the time art was seen as a potential growth market in Germany, he says.

“The sense of community was very strong and there was an emergent moment around the issues I was interested in, of reassessing what Web 2.0 was doing,” he says.

“There was a core group of artists and somehow I stumbled right into the middle of that. It was a really exciting time and it was a really collegial moment, where we all thought we were working on the same project to a certain extent and that lasted a few years. It was such an exciting place to be, in that moment.”

Now, nearly 10 years since he first moved to Berlin, Denny has settled into his life and artistic practice there. He has a 75-square-metre studio in Wedding, and lives not far away in Mitte, in the centre of the city.

“I’ve been incredibly lucky with this country,” he says. “I have a great studio, which is not very expensive; I have a great apartment, which is not very expensive; I am able to employ a couple of people, which is getting more expensive but still very much worth it.”

He says not everyone in his community from those early days has stayed in Berlin, and admits that while he hasn’t completely integrated himself – but is taking German lessons again – living in Berlin has worked out for him.

“As the city has developed I’ve also developed in the way that I’ve related to it. One of the things it has afforded me to do is found an institution here myself with my former professor at Frankfurt and Angela Bulloch, who is a British artist who came to visibility during the YBA [Young British Artists] moment in the ‘90s.”

As the city has developed I’ve also developed in the way that I’ve related to it.

The institution is a mentoring programme for younger artists moving to Berlin fresh out of their masters programmes and helps to connect them with more established artists, with studio visits every two weeks.

“That is something that can exist here, it has been supported by public money to a certain extent. That has been an amazing opportunity that has come from Berlin and Germany that would have been harder to start somewhere else.”

Denny says Berlin continues to draw in the international art community.

“It’s a place where people who travel to a lot of cities to see shows around the world come to. There are a couple of events here for people who are looking to see major international shows… and there are a number of institutions that are of high visibility in other countries… so I think people come and visit certain artists here that then means that there is an eco-system around that.”

He still receives grants from Creative New Zealand on a project-by-project basis, such as his installation at the 2015 Venice Biennale, but says he knew early on that relying solely on government grants to fund his work was unsustainable.

“I wanted to develop some sort of private-enterprise-like sales-based structure for what I was doing. I thought if I couldn’t really do that then perhaps I wasn’t really doing the right thing or I wouldn’t have felt comfortable continuing, so I was lucky enough to be able to continue that up until now.”

Denny returns home every one-to-two years, usually tying some work or an exhibition in with the visit. He’ll next be in New Zealand in December for the opening of ‘The Founder’s Paradox’ in Christchurch.

Image Credits:

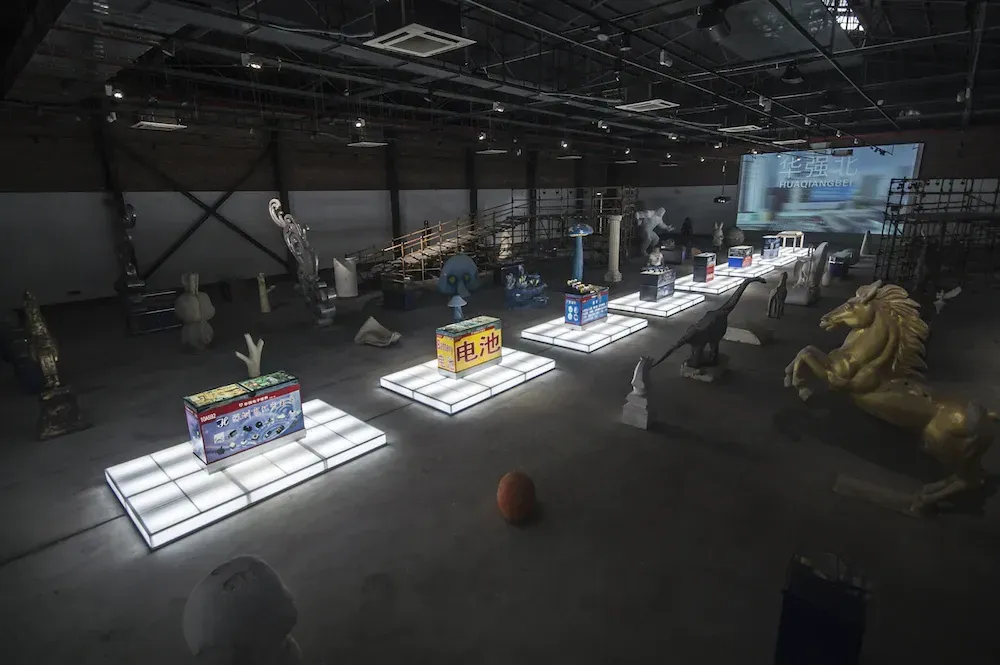

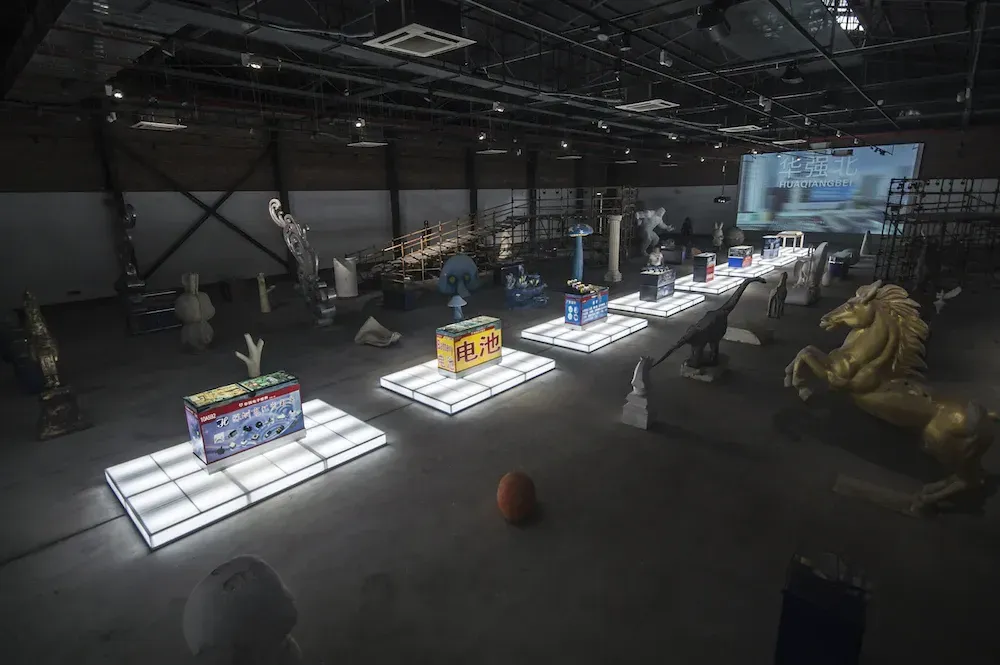

Real Mass Entrepreneurship (2017). Installation view at OCAT Shenzhen, China.

Photo courtesy of OCAT Shenzhen.

Simon at Café Einstein, Berlin. Photo by Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff.

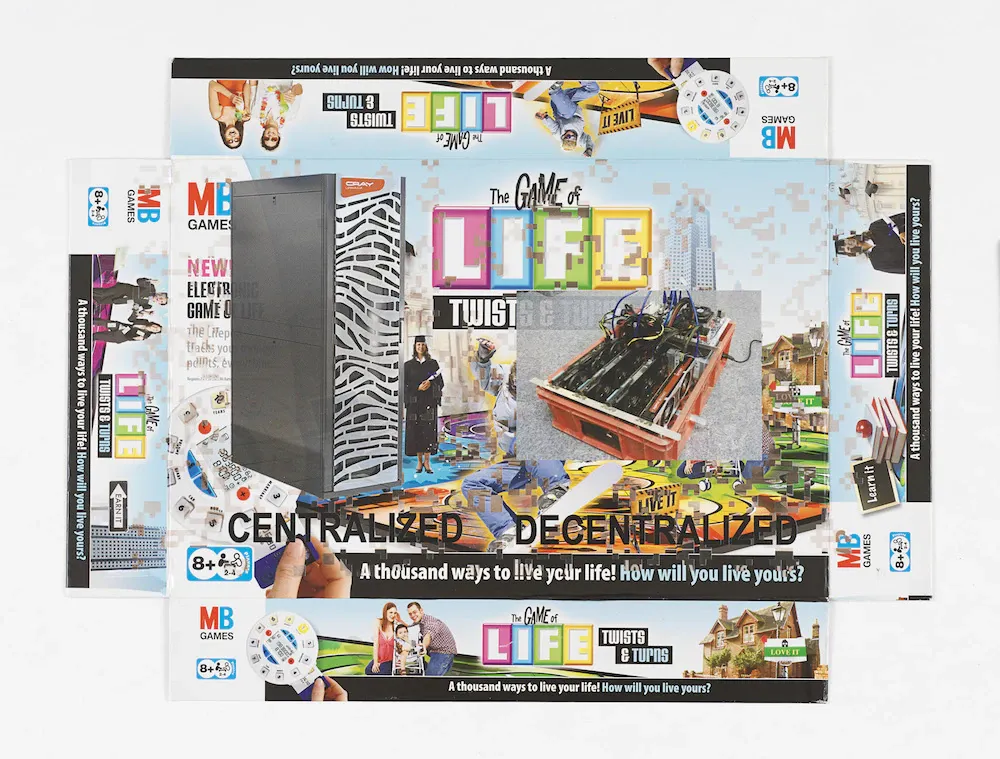

Centralized vs Decentralized Conway’s Game of Life Box Lid Overprint: Twists & Turns (2018).

UV print on Twists & Turns Game of Life box lid, 39.5 x 53 cm. Photo by Nick Ash.

Games of Decentralised Life (2018). Installation view at Galerie Buchholz, Cologne, Germany.

Photo by Lothar Schnepf.