Heart Talk: The Vastness of Blue, the Depths of Black

Tunmise Adebowale opens poetic eyes to the practices of Ruth Ige and Mary Dah Fairy, two artists whose canvases are imbued with the deep blues of Blackness.

There is a passionate connection between the colours blue and black, a link that lingers in the margins of both theory and experience. Blue, in the realm of colour theory, signifies depth, a tranquillity that teeters on melancholy, an expanse that is as deep as it is unreachable. It is the colour of longing, of horizons that dissolve into sky and sea. Black, by contrast, is the shadow that gives blue its resonance, the undertow that deepens its stillness. Together they form a dialogue between presence and absence, between what is visible and what is felt, between the known and the unknowable. In colour theory, black is considered a non-colour because it absorbs other colours. It swallows all others in the visible spectrum in an act of profound absorption, of taking in and holding what the eye cannot separate. Blue, on the other hand, announces its presence with a softer intensity. It refracts rather than absorbs, scattering light to create openness, endless horizons.

There is a singularity to the colour blue, an inheritance of the ocean’s vastness. Yet blue is never one thing. It shifts in the mind’s eye — dancing in the shadowed depths, cerulean as it breaks into the sunlight, ultramarine in the breathless expansion of sky above water. Blue, by its very nature, resists containment, and it is the most delineating of colours, evoking borders, edges, horizons.

Where black consumes, blue disperses; where black is culmination, blue is expansion. And yet, they are not opposites but silhouettes cast by the same hand. If black absorbs all colours, it also absorbs all meanings projected onto it — burden, brilliance, erasure, reclamation. It takes in the gaze of the world and transforms it into something uncontainable, something that lives beyond what is seen. These colours do not merely complete each other; they insist on each other. In their interplay is the language of dark and light, of longing and being, of identity that is not fixed but tidal; rising, falling, and reshaping what came before.

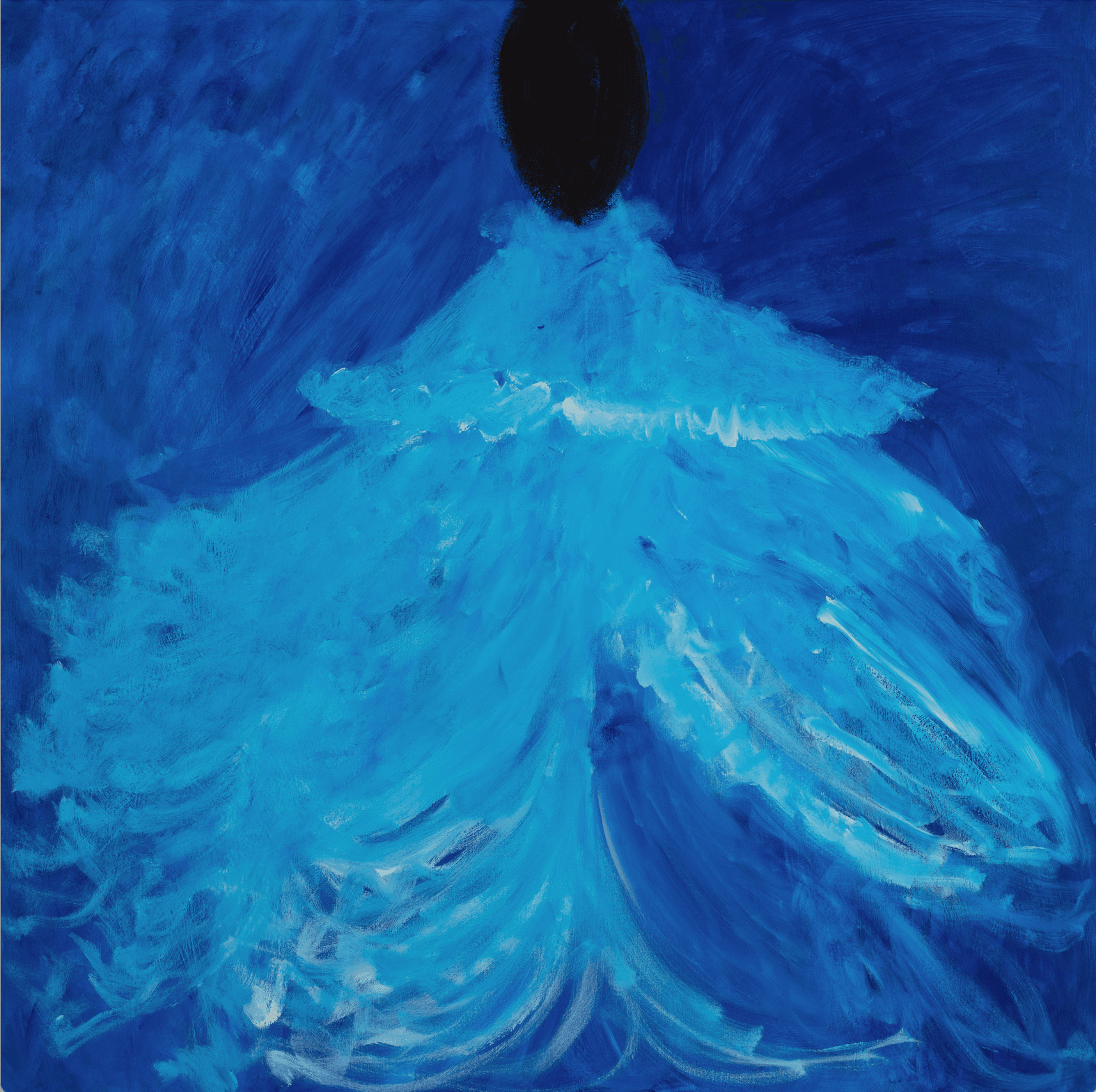

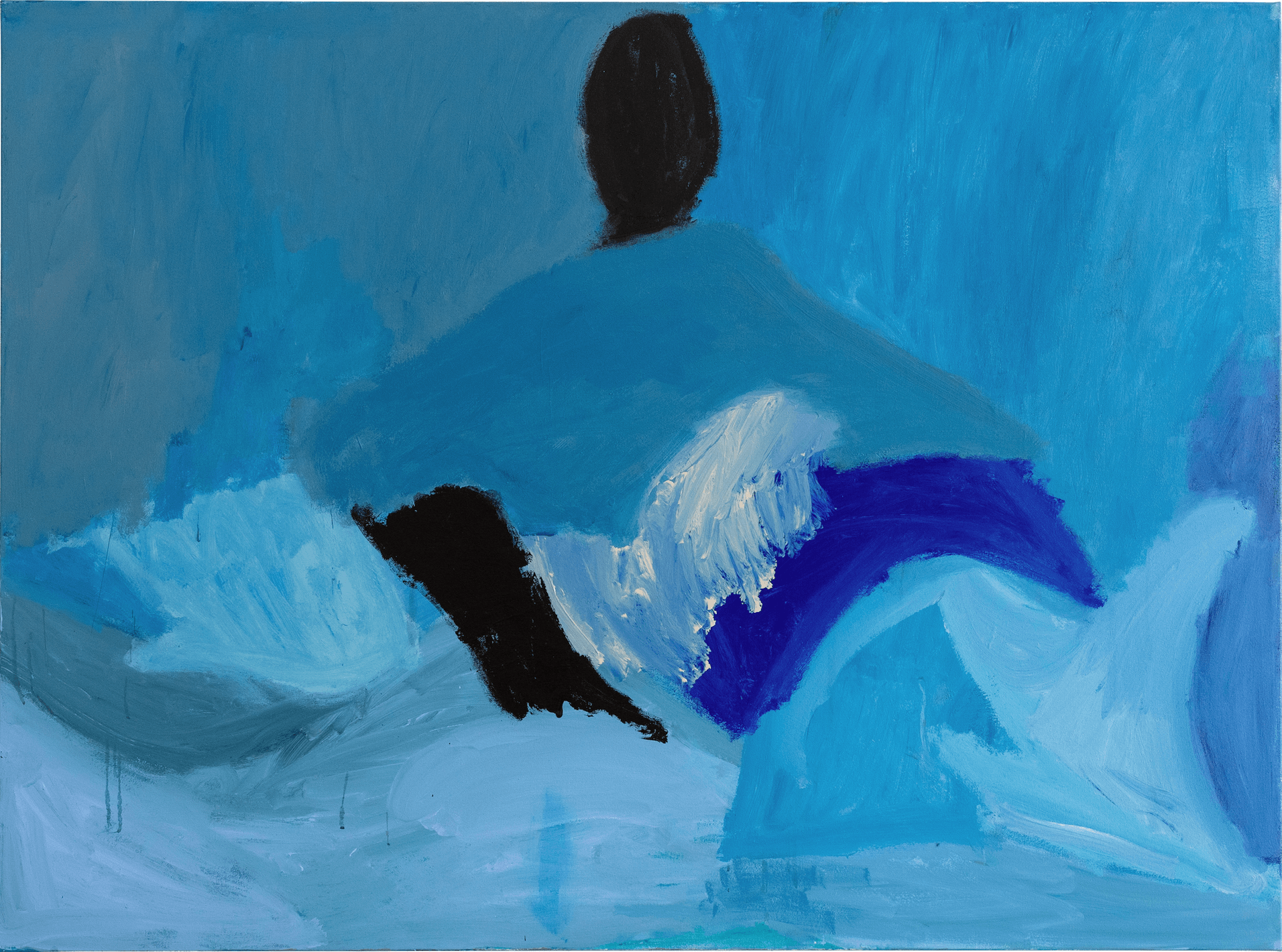

Ruth Ige is a painter based in Tāmaki Makaurau, and her works explore the multiplicity of Blackness, the ways it intersects with art history, and the fluidity of Nigerian identity within a diaspora. For Ruth, Blackness is not just a question of representation but an exploration of its many layers — its history, perception and undeniable presence. The blue in her work, singing the melodies of the ocean, becomes a bridge between places left behind and the new ones she has come to inhabit. These hues carry the weight of migration and memory.

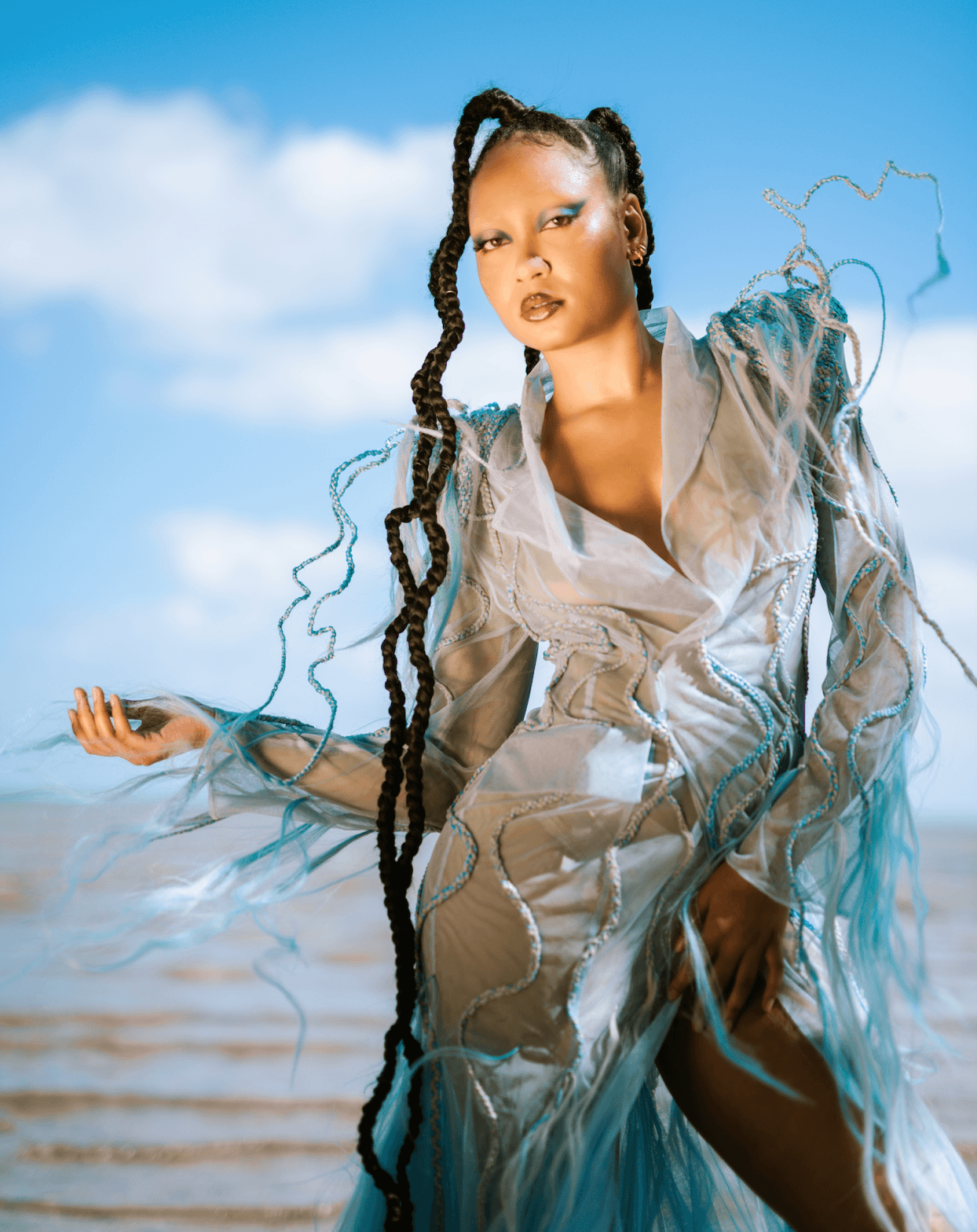

Mary Dah Fairy, also based in Tāmaki Makaurau, channels her identity into a different medium: braided hair art. She weaves strands into intricate patterns, each twist and braid an affirmation of Blackness and an assertion of belonging. Trained in media and graphic design, Mary’s current practice embraces the tactile, intimate nature of hair as a canvas, a site of both creativity and resistance. For Mary, the braids are fluid, like the water’s currents, embodying the adaptability and resilience of Black identity in a predominantly white New Zealand settler society.

Blackness moves like the ocean, expanding and contracting. “You can’t know all about Blackness. Blackness is always moving. It’s not stagnant,” says Ruth. She explains that being fluid is central to her art, and a response to the battles she has encountered upon arriving in New Zealand. “The [people] were just all staring at me. I was like a creature. It felt really strange and scary.” In Ruth’s art, fluidity manifests in the way her figures hide and ripple, not allowing themselves to be contained in one light. Mary succinctly describes the issues people in New Zealand have regarding Black people — stereotypes. In Mary’s work, hair becomes a metaphor for the ocean itself — constantly in motion, reshaped by the currents of experiences of a Nigerian diaspora who are mixing their own cultures together. “In the art space in New Zealand, Blackness is both hyper-visible and misunderstood,” says Mary. This is one of the reasons that artists like herself and Ruth paint visions that push back against rigidity: to offer Blackness as dynamic, unpredictable, and a living, breathing and bleeding lake that resists singular definition.

“I use mystery and secrecy as a form of empowerment,” Ruth explains, describing how her figures remain partially obscured, their features protected from the assumptions of the viewer. Like the sea, her paintings contain views that cannot be fully seen, refusing to lay everything bare. The blue in Ruth’s and Mary’s works are vessels of water, so dark it shimmers blue under the light.

For these artists, blue is not merely a hue but a spectrum of meanings, a vibration that pulses through their Nigerian diaspora identities. Blue carries emotion, a space where sorrow and new life coexist. Ruth sees the duality in the muted shimmer of the Nsibidi-laden Igbo cloth of her heritage, also known as ukara ekpe, where symbols conceal as much as they reveal, fabric that withholds unspoken truths. Indigo, steeped in Yoruba traditions of adire dyeing, becomes material and metaphor — a connection to an ancestral home that, for the half-Yoruba, half-Igbo artists, remains intimately known and irretrievably distant. Blue, fluid and vast, ties their shared heritage into a bigger question, asking — how do we reconcile being both of a place and apart from it? Do we swallow the bones of our history?

What lingers in Ruth’s and Mary’s stories — and their art — is the quiet realisation that we are all mysteries to one another, pieces of ourselves that are kept hidden even from those closest to us. Scientists and researchers proclaim their praises at all that Western science has categorised in the Milky Way, at all the skeletons and treasures we dig up (or steal) from Papatūānuku, yet why have we only discovered 5 percent of the ocean? Why can we not honour the sea as a mutable, mysterious lover that shifts, caresses or strangles us, when touched too much? Encountering Mary’s and Ruth’s art is to wade into an ocean of overlapping stories, where identities ripple, where the act of looking becomes an exercise in accepting that some depths will always remain unfathomable.

Art has long been a negotiation of visibility. To paint is to take up space, to braid is to kiss our roots. Blackness, rendered in paint strokes and hair extensions, is an assertion of presence. To speak Blackness through art acknowledges fluidity, and holds our people with the reverence they deserve. For Black artists in the diaspora, art and crafts are not merely creative, they are declarative. The art says, we are here. I hope more Black artists of the diaspora realise that they are not merely adding to the broader canvas; they are redefining its very edges, reshaping its contours to hold multitudes. Continue to craft your art, for it is like the ocean, flowing across borders, and lighting up the depths where black and blue meet and make something luminous.

The HEART TALK Series is brought to you Art Makers Aotearoa and was commissioned and produced by Van Mei, with copy-editing by Marie Shannon and funding support from Creative New Zealand.