Inside The Toi Māori Wānanga Most Couldn't Afford

In the spirit of celebrating Matariki, I attended my first Kaihaukai - food, storytelling, and gift exchange - hosted by The Realness at Ima Cuisine.

My tablemates were discussing how fantastic this evening was when talk arose of another gathering happening at the Aotea Centre later in the week. As it was pretty expensive (with tickets at $335 a pop), I let it float over my head before tucking into the rest of my crayfish bisque.

I was happy though, knowing Māori communities were starting to mobilise ā tinana (in the flesh) again after this overly drawn-out tea break (aka the pandemic).

Later a friend messaged with a spare ticket. So I thought, 'Oh cool, I'll go tautoko and get to see others after so long.' After that, I was then invited to write about the event, so gave myself a distinct role (beyond honourary 'plus one') to act as a witness to the proceedings, embracing all the multiple hats I wear: as a Māori artistic director, contemporary dance artist, and member of our pan-iwi local and global community of activators, makers, dreamers, and, let's be honest - 'Matatini sideline commentator' (so aptly coined by Elisapeta Heta).

In full transparency, I am a person who doesn't read reviews before I see shows; I don't care how many rotten tomatoes a movie might have. So my general tactic to stop being overwhelmed by details is to check the schedule and only look at the following upcoming session.

Unfortunately, due to managing home-life balance, I missed the first sessions (pōwhiri on Day 1 and Robert Jahnke's keynote opening address on Day 2). Nevertheless, I gleaned matauranga from all the sessions and informal conversations (literally, the water cooler was right next to the tea).

This retelling draws from a diverse range of communications to pull these threads of whānaungatanga together. From whispering to the person next to me, bumping into long-lost colleagues on multiple staircases (the Aotea Centre is a maze), and engaging Indigenous eyebrow morse code across a crowded room. I was even texting responses to my mate seated one person away from me (IYKYK).

But, of course, we all know that the real kōrero is where long-held connections are replenished: "has it been ten years since we last saw each other? Omg, you look so well".

Jack Gray (Atamira), Elisapeta Heta (Jasmax), Zoe Black (Objectspace). Photo: Supplied.

One of the understandings I gained looking retrospectively at the entire wānanga is that no matter what, Māori cannot, for the life of them (us), stick to a western time limit when engaged in the act of kōrero.

And the reason for this boils down to the spiritual and liminal interweaving of acknowledging ancestors, faces in the audience, tuakana, the mana whenua, and recognising what was done just before your turn.

The overlaps of cultural ideology centre on the role of the house metaphorically hosting us - aka The Auckland Art Gallery - which I heard did not have the capacity for the expected audience numbers. The staging at the Aotea Centre heightened the mystique of Toi o Tāmaki - like a missing backdrop (entity, partner?) to the ongoing and unseen fallout (rebuild?) post- Toi Tu Toi Ora (NB: the exhibition that dares not speak its name, or you know who).

My acknowledgements then go to Nathan Pōhio (Senior Curator, Māori Art), his role tasked with raising the profile of Māori art at the Gallery and fostering an environment encouraging Māori engagement and visitation connection. And to Te Arepa Morehu (Head of kaupapa Māori), who held kaitiaki space throughout most of the formalities as mana whenua do.

Ngā mihi.

Te Rangi Tuatahi - Day One

He kōrero whakapuaki | Keynote Opening Address: He Atamira a Huatau: Staging Images, Contemplating Forms: Māori Art & Transformation

I walked in late with my cool lanyard and programme. I was scanning the darkened room of a couple of hundred people (mostly masked) seated on two blocks facing a stage with two projection screens. I find my people near the front.

Looking up, Ngāhuia Te Awekōtuku MNZM (Te Arawa, Ngāi Tūhoe, and Waikato), in a sexy black leather jacket and a spiky white defiant buzzcut, speaks deliberately and eloquently to "establish a conversation about what art is."

Ngāhuia Te Awekōtuku, Photo: David St George. Courtesy Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

She covered the 1973 founding of Ngā Puna Waihanga - the national body of Māori Artists and Writers - a platform that gave members "inspiration to be bold in all of our spaces." Leading to the roots of Te Māori, the landmark exhibition of Māori art in 1984 (then continued until 1987) changed how people viewed Māori art in an art gallery (outside of a museum) or regarded taonga as artworks (not artifacts).

This revolution kickstarted Pākeha consciousness about taonga Māori. But, as she shares the idea that 'Toi' is only a recent word used for labelling Māori art, the realisation strikes me that as a performing artist, I am a rarity in this room. Why any distinction remains in the Māori world between visual and embodied arts practice is an ongoing anomaly to me.

Wheako Whaiaro | In Conversation Ngā Kaikōrero

Rānui Ngārimu ONZM (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Mutungā) and Nathan Pōhio sit on the podium, engaged in a gentle back and forth about her work as a Māori weaver and textile artist.

They show images of a smiling Dame Patsy Reddy at her inauguration as the 21st New Zealand Governor-General (serving between 2016-2021). She explains how the kakahu made by Paula Rigby (Ngai Tūāhuriri) fit the best on Dame Patsy at the time (apparently, she is not a tall woman).

Photo: Jack Gray.

Next, she talks about the founding of Te Roopu Raranga Whatu o Aotearoa, the national collective of Maōri weavers who nurture, develop and preserve the tikanga of raranga, whatu, and taniko in traditional and contemporary contexts.

Trails of the past are woven, referencing Te Kāhui Whiritoi - an organisation meeting biennially with the management committee of Te Roopu Raranga Whatu in conjunction with the National Weavers Hui.

Next, she moves into Te Rangi Hīroa's research into the evolution of Māori clothing, sharing an anecdote of how settlers mistook Māori as a clump of bushes that moved. We see images of garments she has made, the kahu poa made of harakeke, pākihi, muka, emiemi, and tikumu, and are told of the purples, reds, and natural brown dyes as they dry. Poa cita, commonly known as silver tussock, was a traditional food offering nourishment (of the mind). Houhere (or lacebark) and Houi (or ribbonwood) were processed and extracted. "The way it kills itself and demands you use it."

Ranui's approach to Pa Harakeke is that it is her livelihood "when I can create, nurture and learn." She didn't come to weaving by sitting "at my kuia's knee" but through marriage, when her mother-in-law and husband's Ngāti Porou whānau taught her how to prepare kiekie (the most valued plant to weave after harakeke) to sell. (I noted: *she laughs).

She concludes with questions about Te Ra, the last known Māori sail in storage in the British Museum for more than 200 years. A group of Māori researchers who embarked on a three-year project to learn about this sail now say the Museum is planning to bring the taonga back to Aotearoa - though they're not letting it stay.

"They don't know where it came from or who made it. So who does it belong to? It belongs to us. To all of us."

Te Pae Ringatoi: Ko Te Whenua Hei Mātāpuna | Artist Panel: Whenua as Source

Photo: Jack Gray.

This panel of wahine ātaahua with chair Carla Ruka (Ngāti Whātua, Ngāpuhi) became the go-to reference point for the subsequent discussions, as people picked up on the clarity, the informed, and clear communication skills exhibited by these young women.

Nikau Hindin (Ngāi Tūpoto, Te Rarawa, Ngāpuhi) shared how meeting revered Māori customary technologist Matua Dante Bonica was one instance of how she encountered kōkōwai (clay). She described her work with whenua paints as inspired by dreams of Pukepoto, 7 kilometres west of Kaitaia, and her practice honouring materials and slow processes. From Aute, as barkcloth (paper mulberry) leading to pakiwaitara of Te Kiri o Tāne (the skin of Tāne) seeking his equal. His procreative longing leads to asking where he might find the essence at Kurawaka, Papatuānuku's menstrual soil. It is there that kōkōwai transforms into Hineahuone (the first woman).

The mahi of Nikau Hindin. Photo: Jack Gray.

Raukura Turei (Ngāitai ki Tāmaki (Tainui), Ngā Rauru Kītahi) is the first to claim "the fractured shame deep in my whakapapa through colonisation." He kapiti hono, he tatai hono. When joined together, it becomes an unbroken line.

Raukura shares the joy of connection that spans many generations and traverses the east coast of Tikapa Moana to the rugged west coast of Te Tai Hau a Uru - Te Mānuka o Hoturoa. She finds the blackest onepū (sand) to use as a core material for her visual artworks, drawn there to honour her kuia and shed her mamae.

"On my own terms, as I connect to my tipuna, the next generation allows those openings."

Nova Paul (Te Uriroroi, Te Parawhau, Te Māhurehure ki Whatitiri, Ngāpuhi) works with Analogue film 16 mm to capture the mauri of the image and world of light. This reflection of the aura of light, matakite, and allowing the rakau (trees in the forest) to guide her is about re-establishing the practices of the maramataka, the Māori lunar calendar.

Wheako Whaiaro | In Conversation Ngā Kaikōrero

Photo: Jack Gray.

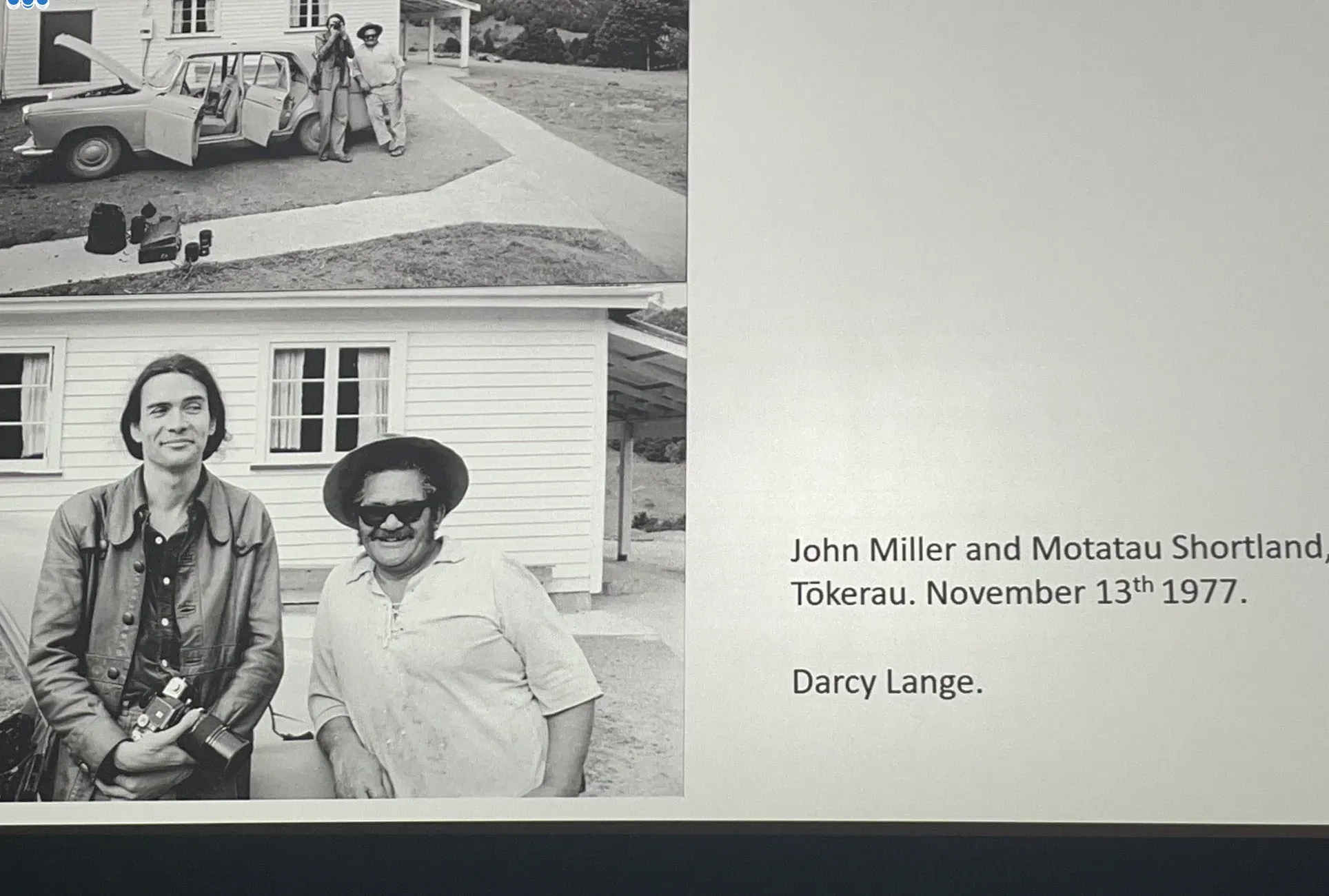

This respectful kōrero asks, 'What does it mean to take photos from a Māori lens?’ John Miller (Ngāpuhi, Ngaitewake-ki-Uta), an independent social documentary photographer renowned particularly for his protest images, and Natalie Robertson (Ngāti Porou, Clann Dhònnchaidh) both seem to agree that 'you can't sweep things under the carpet..'

In a long-ranging talk, we hear Millers' photographic capture of Indigenous sovereignty occurring at Waitangi Day events, Māori Women's Welfare League Conferences, and behind the scenes of a Marae. This legacy rectified the cultural amnesia of the times by embodying Matauranga Māori and exemplifying Te Ao Māori as a way of being.

Both of their work explores environmental advocacy as documentary photographers. Robertson’s centres the question of “How can image making express kaitiekitanga / kaitiakitanga as an ethics of care for whenua, awa and moana?

Millers' photos of the Ngāti Hine block connect to the pine planting there in Matawaia, roughly 40 km inland from Moerewa, south of Kaikohe in Northland. Another series he did inland from Ōmaio, on the fringes of Raukūmara Pae Maunga reflects on the restoration and collapse of the forest, iwi working together to save it, though now the birds are gone. We hear of forestry schemes in Waikākariki on 99-year leases, land subjugated to the good of everyday wellbeing. That pastoral deforestation leads to the widening of the river and a loss of depth: "What is happening inland is happening downstream."

Te Pae Ringatoi: Kia kitea ngā tūtohu whenua i te tāone | Artist Panel: Making Cultural Landscapes Visible in the City

Nathan Pōhio chairs this quartet of articulate, badass activist artists.

It's been a long day, and we are ready for a rock n roll session. But, even though it's been a unique and exciting day, the ability to stay so profoundly listening requires a new kind of stamina.

Graham Tipene (Ngāti Whātua, Ngāti Kahu, Ngāti Hine, Ngāti Haua, Ngāti Manu) shows a video of spatial projects and asks, "How do we hold onto the stories of our ancestors?" As mana whenua to Tāmaki Makaurau, Tipene shares how growing up in this city, it was rare to see "us" reflected. But then, he says probably the most profound statement of the event: "I was born and raised here, have lived here my whole life, and will probably die here."

He questions what supports the next generations you will never meet. As a born and bred Aucklander with whakapapa elsewhere, I have never considered some of these points. And it hits me somewhere inside. He doesn't use the word art but sees his work as a cultural expression everywhere. His comment about ensuring homeless people had a place to go to before he redesigned Myers Park area - because it is his responsibility as mana whenua - moved and made me understand his visibility and success in the community. “Therein lies the potential as well as the place".

Elisapeta Heta (Ngātiwai, Waikato Tainui) is right in her element, smiling, giggling, and just being a sass queen. She begins by acknowledging all of the wahine who spoke and her hope when she was starting that she could be like her tuakana one day. "These moments link back up to people we look up to and remind us of the incredible amount of connections."

Next, she discusses western constructs through her 9am-5pm, Monday- Friday job as a Principal at Jasmax. This livewire disrupted the "Old Boys Club" by making Māori spaces physical for Māori and on Maori terms. In her work, she aims to discover what these new hubs could be and where we might find expression in our built environment. Her various projects share pūrakau of place, flipping the script on how to embed matauranga in every detail.

Photo: David St George. Courtesy Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

Rachel Shearer (Rongowhakaata, Te Aitanga ā Māhaki, Ngāti Pākehā) discusses Flooded Mirror (2011), her permanent sound installation situated in the Wynyard Quarter. It’s based on land reclamation, sands shifted by tides and applications to atua. The sounds of life in the ocean, fish communication, and non-lingual human vocalisation show the physical connection of the volcanic pathways—humans as minerals and becoming rock.

Brett Graham (Ngāti Korokī Kahukura, Tainui), the sculptor, sees the insensitivity of colonial structures as deliberate attempts to not indigenise space. He shows his sculpture based on the story of the local god of volcanoes, Mataoho, located in Hurstmere Green, Takapuna, drawn to the relationship with Mahuika.

Jack continue his insights into Toi Te Kupu | Whakaahuatanga 2022 |Wānanga Toi Māori with Te Rangi Tuarua | Day Two - click here.