Jack Trolove: “I’m an artist”

Written by

Working from his studio in Shelley Bay, Wellington artist Jack Trolove is busily preparing for his upcoming exhibition at Whitespace Gallery, in Ponsonby. This will be his third exhibition with Whitespace. The show runs from 26 September to 21 October, and is included in the line up for Artweek Auckland - a 10-day festival showcasing and celebrating the visual arts and artists of New Zealand.

Jack holds a Master of Fine Arts with Distinction. Some of his artistic achievements include being shortlisted for London's BP Portrait Award Exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in 2015; selected as a finalist in the 2016 and 2017 Wallace Art Awards, and numerous solos shows throughout New Zealand, Australia, Scotland and Spain. With credentials like these, I find it hard to believe that for the longest time Jack wouldn’t and couldn’t describe himself as an artist.

Balancing his art work with other paid work, Jack works four days in the studio, and two days contracting in the suicide prevention, and LGBTI youth space. Only now that the majority of his time is spent creating art (until recently, it was the other way around – two days in the studio and four days NGO work), Jack has finally gotten over the hurdle of being able to say, “I’m an artist.” “I’ve always had to prioritise paid work.” he says.

Why? Because being an artist is not a “real job”? The way it’s valued in New Zealand, (as highlighted by Barbarian Production’s Jo Randerson) with the all too frequent assumption that the offer of exposure in exchange for services rendered is a fair deal, seems to indicate that perhaps we don’t really think being an artist is a “real job.”

Talking about paid work in the Kiwi culture and it’s implicit connection to identity, Jack says, “Here, when people are asked what they do, they often respond with what their job is. In Spain I found it wasn’t like that, they want to know what your purpose, or passion is.”

Relying on kitchenhand work to pay the rent in the past, Jack shared a story about trying to find work in Barcelona, where he had a very confronting experience with a restaurant owner, who refused to give him work because he was an artist. “He said it was offensive to him that I was trying to get a job in his kitchen when I was an artist. He told me to go and be an artist and that he wouldn’t give me a job because I shouldn’t be here! Don’t make your living doing what you don’t want to be doing, is what he said to me.”

That conversation happened at a very desperate and pivotal moment for Jack, and at that point he had no other roads to follow. “It was the end of the line, I was down to my last five euros, with nowhere to stay for the night.” He borrowed an artist’s kit, and set up on La Rambla for the midnight shift and began painting portraits. This was the first time he’d made reliable income from art.

Jack went on to work in the UK, where he found, “they understand the value creative work and its social impact.” He ran an arts and social justice programme at the Glasgow Gallery of Modern Art; he worked on homelessness projects, worked with survivors of sexual violence, and with the LGBTI community – all within an arts context.

Returning to New Zealand after working as an artist in Europe, Jack had hoped it would be possible to continue working in this space - and that community arts work would be sustainably funded and valued. The return home was a culture shock, when he told people he was an artist, he was often met with, “yeah yeah, but what do you do?” – again implying that being an artist wasn’t valued as a professional job option.

Jack worked in the community arts sector, running various projects in Wellington, but often at less than minimum wage. It wasn’t sustainable long term. Working incessantly and constantly in debt, he says, “It was all work that I loved – the community projects, and my own practice, but in 2010 I reached total burnout, and I couldn’t physically manage any more.”

“This is what we love and what we do, but often the way the systems work here make sustainability a real challenge.”

The cost of making the art is often overlooked, unpaid time is usually a given, and in Jack’s case the material costs of making a painting are often huge. Jack also pointed out that for every painting that makes it, there are often two others that didn’t – driving the cost of materials up even further.

So Jack moved to Auckland and reinvented himself, employed in a salaried, full time job, which he loved. He took a sabbatical, and for two years didn’t even tell anyone he was an artist. The validating thing that inspired him to return to art was visiting Colin McCahon house in Titirangi and reading on a footnote that something happened to Colin and in response he didn’t paint for two years. Reading this, he says let him know that taking a break was okay, but that perhaps it was time to go back.

Accepting that he had to do things differently this time around in order to survive, Jack formed a relationship with a dealer gallery so that he could concentrate on making the art and not have to worry about building galleries from scratch and doing all of the promotion himself as he had done with artist run spaces. “Making the work is full on enough, and I wanted to be able to put my energy into this part of the practice” he says. He has also acknowledged that having another job is vital to his equation. Working as a contractor now, he has flexibility and autonomy over the types of work he takes on, which he finds suits him well. A constant rebalancing act, in three years Jack has managed to viably increase his time spent working in the studio from 1 to 4 days, something which he is really proud of having achieved. "A big learning for me has been to listen to my body around where my energy is. Making work that makes me want to get into the studio first thing in the morning, not making work I think I 'should' make. Thats something I can control, and I've learned it gives me energy, which makes life feel better and my practice more sustainable."

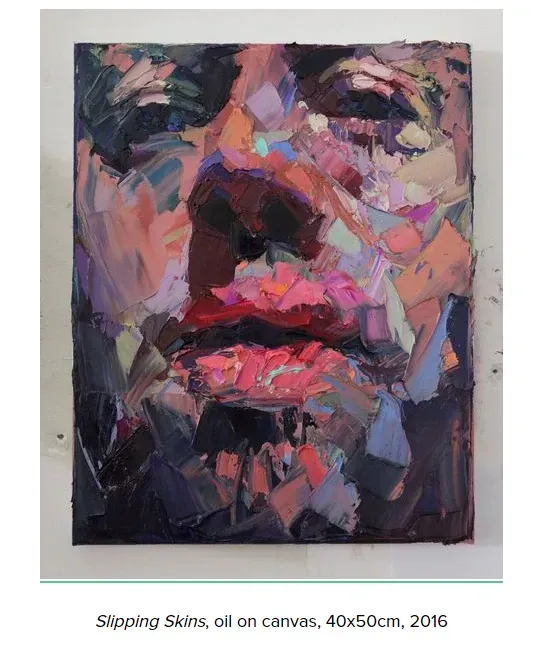

Jack Trolove, Auckland Artweek