Kia Mau Festival: Expect the Unexpected

Sinead Overbye travels through the rich tapestry of Kia Mau Festival 2025 and the threads of Indigeneity that run through its very fabric.

For years, Kia Mau Festival has been the epicentre of Indigenous theatre performance in Wellington. With so many Indigenous artists drawn to tell their stories, the programme becomes a rich tapestry of shows differing in tone, style and theme. What each performance has in common is that the threads of Indigeneity run through the very fabric of these shows.

Whether it be satire, deep commentaries on the world, contemporary dance performances, or edgy experimental shows that make you rethink the possibilities of theatre, Indigenous peoples can do it all.

Join me as I travel through some of my own memories and experiences of Kia Mau Festival 2025.

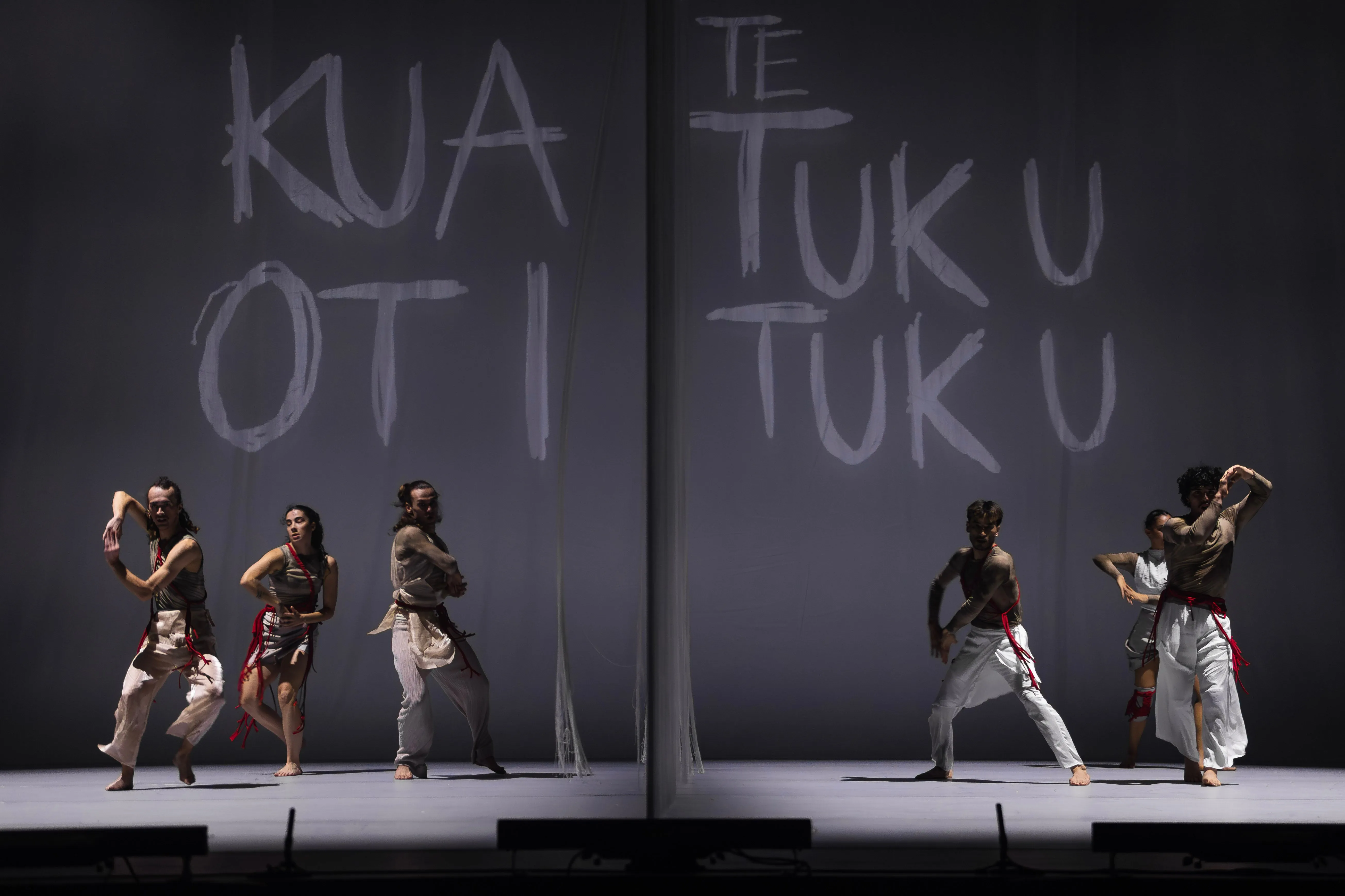

Hero Image: Ka Mua Ka Muri. Photo: Roc+ Photography.

Kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua

For me, Kia Mau Festival begins with a bus ride. 200 students and teachers from Te Wānanga o Raukawa are transported from Ōtaki to Wellington to see the matinee of Ka Mua, Ka Muri. We’ve re-arranged our entire week around this tono. Whitireia – the whare where we learn and exist in Māori immersion every day – is abuzz as we prepare to take reo Māori from our little bubble to the Opera House.

The buses are filled with waiata, mōteatea practice and chatter as we cruise down the Kapiti Coast and into the big city. We gather at the Opera House and send out our thanks – ngā mihi! tēnā koutou! – to the staff as they show us to their seats. This is the first time that many of us have only spoken Māori in a theatre space. For some of us, it’s our first time being at a Māori-choreographed dance show too.

Ka Mua Ka Muri is a double-bill dance show featuring choreography from one of our fellow students, Eddie Elliott and a previous graduate of our tohu, Bianca Hyslop. The first half is a reflection on our past – the trauma we as Māori grapple with, the identity crises, the troubled relationships with our reo. The second half expertly pulls us out of the darkness and thrusts us into te ao mārama.

We meet our tīpuna, who had such high hopes for what they might be able to hand down to us. We meet our maunga, our awa, and are urged to consider them as living beings, and how we might strengthen our relationships even through disconnection. We are ancestors, watching on as our descendants become lost and forget about us. We are descendants, trying desperately to gather lost taonga in our arms. We are staunchly Māori, sending forth a haka that shakes the building, telling the performers, Ngā mihi, ka kite mātou i a koutou, e kore tātou e ngaro.

Unbecoming in a subterranean epoch in-between the collapse of one world and the birthing of another

A vibe shift. You’re in a dark room with music blasting so loud you feel it thrum through your soft foam earbuds. A spotlight floods the space before you. A faceless creature dressed in black begins contorting on the floor. Their limbs move in directions you didn’t know were humanly possible. The crowd of people in the room - the audience - form a circle around the creature. Leaning over them, crouching with wide eyes, hungry.

The spotlight shifts. Another performer across the room. You watch the crowd swarm towards this new light, like moths drawn to a flame. You walk with them. A follower. You wonder what everyone is thinking. What it all means.

A towering platform is wheeled down the middle of the room. A heavy metal drum set. The audience head-banging. A performer garbling through a microphone, writhing on the floor as a light is shone upon them. Like they are hiding or in pain. A fly approaches. The fly is a policeman. The policeman inspects the audience. A woman in the audience inspects him back. Doesn’t back down. Doesn’t move. The crash of drums. The writhing performer stands on top of the policeman as he lies dead. Pig squeals of victory. The performer turns to meet your gaze. You, the observer, devouring them from a distance. They point a finger straight at you. You didn’t expect to be seen. They leap in your direction before the light goes out.

You leave the show after two hours and want to scream. Your senses have been repressed for so long. Your feet ache and your mouth is dry. You take a gulp of fresh air. Wonder what it all meant. What was everyone thinking? But what was it about though? And why is it so important to you, to make meaning?

The event description for DARK! DARK! DARK! says the show was about exploring ‘a subterranean epoch in-between the collapse of one world and the birthing of another’. Which feels entirely true. The show lives on in your mind for weeks. You are processing, analysing, sense-making, figuring it out.

The thing that you can’t stop thinking about – the part that haunts you – is that ravenous look that everyone in the crowd had in their eyes. Drinking in the performance. Leeching off the performers’ energy. You think maybe that was the point. You were all followers, observers, walking around in the darkness, unable to stop watching. Like a doom-scroll through the atrocities of the world. The obligation to never look away.

Romance, genocide and a live band!

It’s the end of the world and you’re on the last flight ever, journeying across polluted skies and over an earth which has been scorched and desecrated. Everyone you know is dead. Your only companions are an AI sidekick, Captain God’s Gift who struts around the plane wielding his holy thumbs and swinging his massive cock, and Death who sits ripping bongs in the corner. You’re the last Indigenous woman to ever exist, and you’re pregnant with God’s Gift’s child – who he is adamant will be sacrificed when they are born.

The show that ensues is described by the creators as ‘an epic First Nations vaudevillian musical nightmare’. The quick witty dialogue and over-the-top crassness have the audience literally keeling over in belly laughter. Audible exclamations of ‘What the fuck?!’ can be heard throughout the crowd as we journey through a sardonic story filled with Blak humour and plot-twists so completely jarring we get whiplash.

The result is a ridiculous ripping yarn that somehow still manages to pack an emotional suckerpunch even as the show crescendos into an unexpected dance party celebrating a bottle of sauce.

A Nighttime Travesty actively works against audience expectations, refusing to give the viewers the type of tear-jerking, touching show about Indigenous struggles and triumphs that people may have come to expect. The show earns its randomness and unpredictability in one of the closing lines ‘When one buys a ticket to a First Nations show, one expects to be gently and respectfully reminded that Indigenous people deserve to exist.’

Having these expectations contradicted was an experience I didn’t know I needed.

Attending an Indigenous theatre festival, you unknowingly bring expectations of the kinds of stories you might experience, and the way these stories might be told. However, to give yourself over to Indigenous creatives and trust them to hold you in the creative space – even if it’s out the gate! – is far more powerful.

Kia Mau Festival this year blew all expectations of what Indigenous theatre can be out of the water completely. It taught me to expect the unexpected, and to become comfortable sitting in discomfort. This, for me, was completely necessary.

While some shows embraced more conventional storytelling, others actively worked against all audience expectations, creating jarring, hilarious, challenging and charged experiences that will live on in my memories for years. A mirror was brought up to us, the observers, and we were forced to reckon with what it means to consume Indigenous experiences. What it means to sit and watch.