Letters to an Emerging Creative: Getting Started

Dear Emerging Creative,

The first thing I want to tell you is that there is no right or wrong way to develop an art career, and any path you choose - provided you are happy with it - is perfectly ok.

What I’m going to tell you is stuff I’ve distilled from twenty years floating in the soup of Aotearoa’s art world, from my observations, what I’ve read, what I’ve experienced as a writer, and what I’ve learned from other creatives.

As I write this, I’m likely going to be making a lot of assumptions about you. For example, I’m probably assuming you went through some form of formal tertiary artistic training.

It’s by no means necessary to a career as an artist, but it certainly makes things a lot easier because it gives you an opportunity to be guided by people who know the territory, make contacts, build networks, and have time and physical studio space to make art.

That’s quite important because later on you are not going to have as much time and space to do that kind of technical work and self-discovery.

If you didn’t go to some kind of art school, that’s cool too. Not every artist is that kind of artist, or wants to be that kind of artist, but much of what I will be talking about has direct application to people who want to develop a critical creative practice and make a professional living from it.

As for writers, there’s a lot of pressure to study creative writing formally – particularly through International Institute of Modern Letters at Wellington’s University of Victoria. The writing programme at Auckland University is also highly regarded. It doesn’t hurt, for similar reasons outlined above.

Personally, though, I think unless you’re a good reader to begin with you probably won’t ever be a good writer, and a lot of what you learn in creative writing schools is stuff that you could probably learn from reading.

After all, writing schools are a relatively new phenomenon and creative writing is very very old. Don’t feel that it’s essential.

On the other hand, what writing schools are very good at is getting you out of your own head and providing feedback, especially if - like many people - you don’t have a lot of writers in your personal life.

Making the art in the first place is often just as hard as building a career around it, so let’s start there.

Nobody said it was easy

Recognise that unless you’ve got an independent income it’s going to be a hard slog. There is nothing wrong with having a side hustle, or even a primary job where art has to take a second place. That’s just being pragmatic.

Don’t rush to become a full-time artist or neglect to find some kind of life-work-art balance. You run the risk of burning yourself out, especially if there are other responsibilities in your life that need to be taken care of.

Making space and time for making art isn’t always easy. Virginia Woolf once wrote that the thing that empowered her as a writer was her independent income and “a room of one’s own”.

Unfortunately, that’s not always realisable for everyone, but that doesn’t have to be a liability. There are a lot of artists who work around other roles like being a full-time parent or carer without too much compromise.

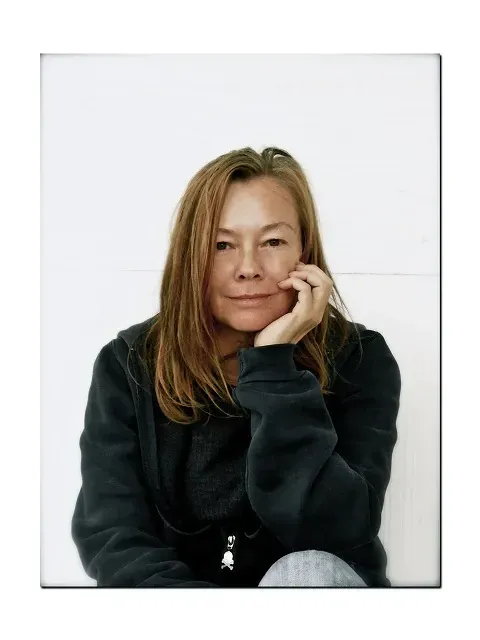

Author Megan Dunn had this to say about this complicated topic:

“Brutally, my work life balance has been nil by mouth for the best part of twenty years—which probably makes my life sound worse than it is. I drink flat whites out in cafes, I have paid for avocado on toast, is the problem simply me? I struggle to answer that honestly.

“For many years, my enormous student loan has been a source of private scolding shame. I took it out when I was seventeen. I wrote briefly about my loan in Things I Learned at Art School—but my feelings about my loan aren’t brief.

“Art is my life’s work but so far that has not been very well paid. My financial advice? Look at the rule, not the exception to it. Also, don’t take advice from me.

Megan Dunn. Photo: Yvonne Todd.

“I vote Labour for what it’s worth and write in the mornings now I am in my forties. If I edit in the evenings, I’ll lie awake, the hamster wheel in my brain still spinning. I’ve never written solidly for eight hours in a row. I squeeze in writing around the edges of paid work. My first book Tinderbox was a book about a bookseller who wanted to be a famous writer. That writer was me. After a while the hamster sees only the wheel, still spinning. But it can’t get off—that would upset the balance.”

Sometimes it’s even an asset. Look at the drawings of Joanna Margaret Paul – her sprightly line, minimalism, use of negative space and restricted palette are things that come out of a practice that snatched whatever time was available. Quite often the subject was very domestic, or portraits of her children, but all of it brilliant and none of it a compromise.

Rules of engagement

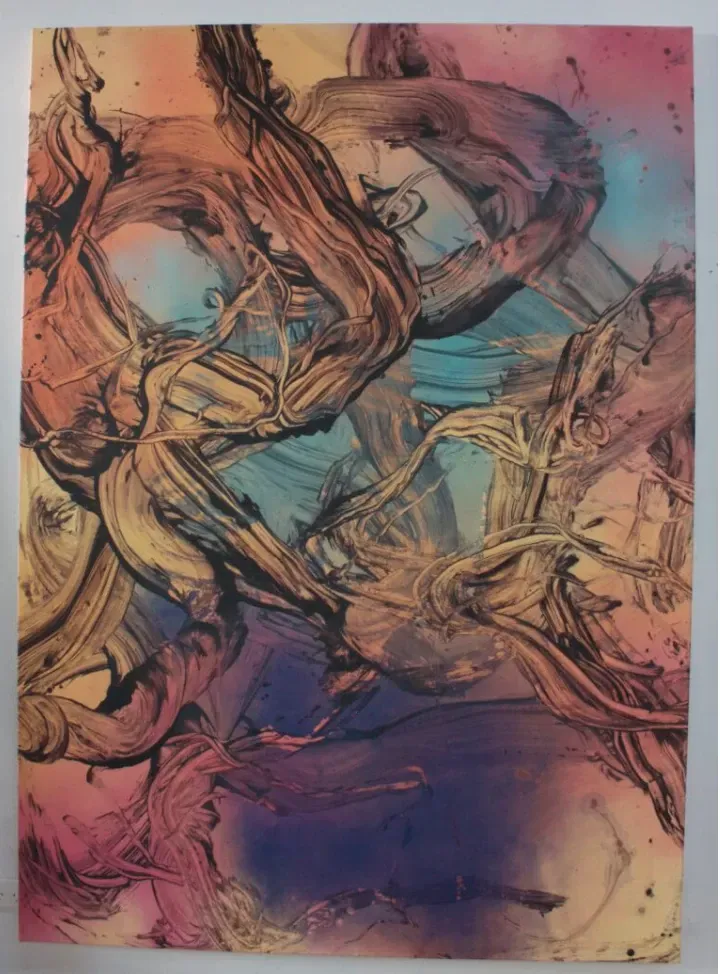

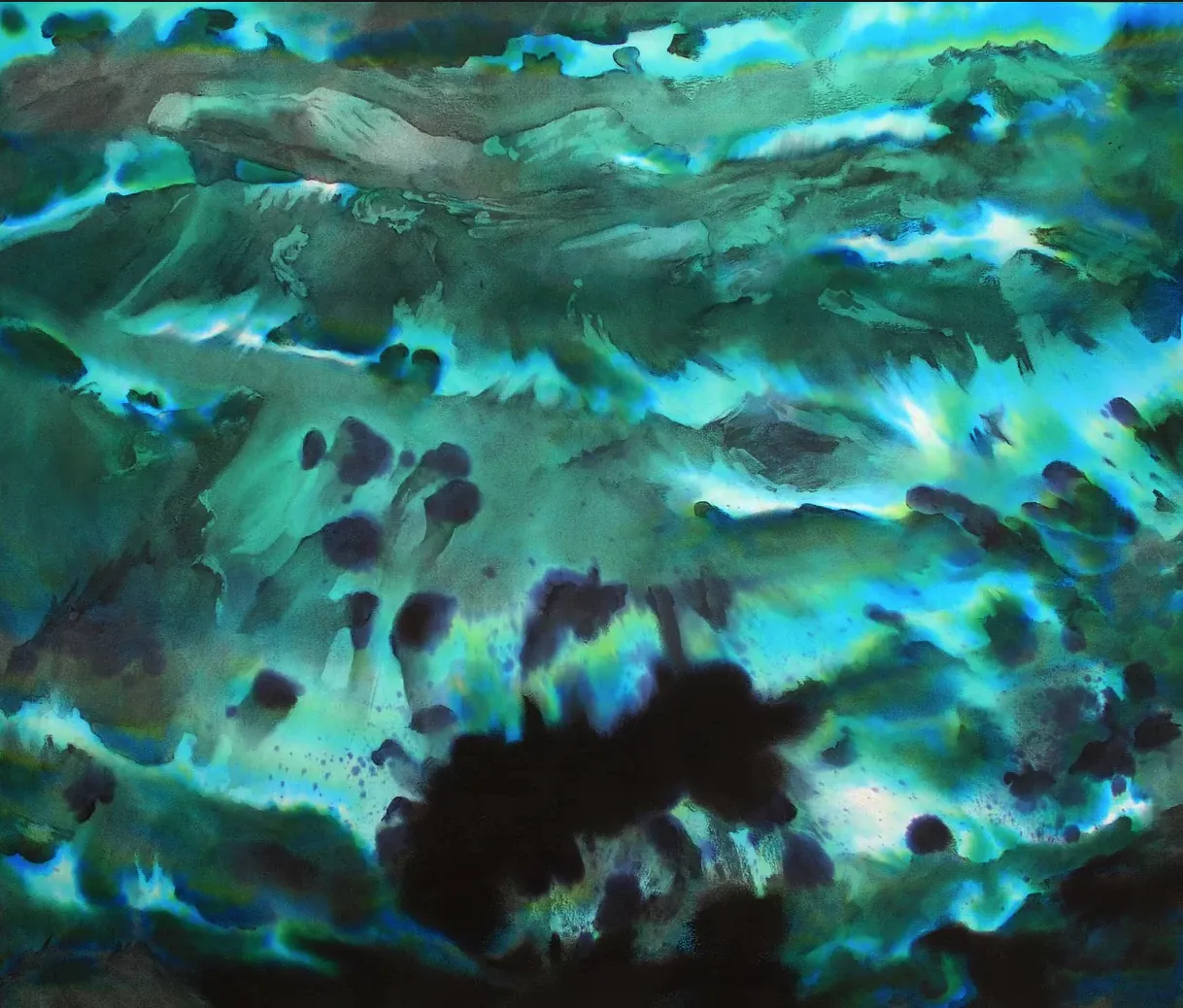

Judy Millar, Untitled (2018) acrylic, oil on canvas.

The making is often the first big hurdle to overcome. There is no wrong way of making art, but some approaches are probably going to make better art and be healthier for you in the long run.

Working towards exhibition or commission deadlines can cause a lot of stress, and while some people find their creative spark under pressure, most people struggle. Like a recalcitrant stool, don’t force it.

That doesn’t mean that if you don’t feel the creativity flowing that you should do nothing. A little procrastination now and then is fine, even healthy, but at the end of the day making art is still work and there are other things adjacent to making you could be doing – like cleaning and organising your tools, preparing materials, learning new techniques, researching and taking notes and so on.

New Zealand artist Judy Millar offers her own approach to structure and discipline, her “work rules”:

“Making art can be a battle. And as in any battle, you’re forced to engage with your foes. I’ve met my own enemies of sloth, procrastination, a love of distraction and plain old fear many times over. To help me meet the enemy fair and square, I’ve devised a set of seven rules.

“1. The first rule is to make sure that I do something in the studio every day. This is regardless of whether I’m tired, not feeling well or am preoccupied with some life event, whether it’s raining, the sun is shining, it’s too cold or too warm. Because if we wait until the stars are aligned and we’re on top of the world, we’ll never get started.

“2. Rule number two is I use whatever I have available to progress the work on any given day. If I have only 15 minutes, I use that 15 minutes. If I am missing a colour or a material that I really need but can’t access easily, I look at what I do have and use that instead.

“3. I try to go to work in the studio around the same time every day. A daily routine helps me. I like to do any communications or meetings in the morning and then begin studio work. That leaves my day open so if I want to keep working on something, there is no necessary cut off point. When I was younger and needed to have many part-time jobs to support myself, I would try to get the paid work out of the way first and then hit the studio.

“4. I prioritise buying plenty of materials to work with. If my shelves are stocked with materials I don’t skimp, and I don’t hold back from trying things out.

“5. I try to come up with three different approaches to everything I do. Those three different ways of going about things often lead to three other ways and before you know it; I have more possibilities to work with than I could have ever imagined.

“6. If on some days I have very little time, I’ll just go and sit in the studio, at least that keeps me connected with the work.

“7. I leave the phone out of my studio. Distractions are a curse. I need to cancel out everyone else’s noise and focus on what’s right in front of me.”

No write or wrong

It’s a bit different for writers, but similar in other ways. I’ve found that my experience in commercial writing has taught me how to put things together really quickly, grind out the words, and then go back over it to supply the finesse.

On the subject of the grind, New Zealand novelist Kelly Ana Morey offers this advice:

“1. There is no muse, writing is daily slog. Establish a routine and realistic daily word counts and stick to it. You’ll be surprised how quickly that word count goes up.

“2. Writing badly is fine, everyone has slow or clunky days. The trick is to know a) that you’re writing badly and b) that after you’ve done 2865 rewrites you’ll get those words either doing their job or deleted.

“3. Write lots. Delete lots. They are not your darlings, they’re just words and they’re free. I’ve squandered millions of the little bastards.

“4. Writing is like being in a dysfunctional, slightly abusive relationship. You give up for a while, but then an idea promises you that this time it will be different. This idea will be the one. Get good at processing disappointment. Destroying dreams is writing’s bread and butter. In spite of this, I still like planning the outfit I’ll wear when I win the Booker. I have very expensive tastes. But hey I’ve won the Booker. When I win the Booker I will give up writing and become a full-time gardener. I will also refuse to do media or go to book festivals, because I’m nobody’s prize pig on show.

“5. Don’t squander first line, paragraph, page and prize real estate. These are all important things. The first three are what gets you published. Winning a First Book prize will get you funding. You only get one shot. Make it count. Don’t let your ego entice you into publishing something half-arsed. Go back and rewrite the damn thing.”

Feel the flow

That said, reading, watching a movie, and listening to music are all completely valid ways of doing the mental work. Often moving between tasks can be a great way of clearing a creative block.

Living is as much a part of making art as anything else. Don’t be afraid to have hobbies.

When the creativity is flowing, the reality is that not every stroke of the brush, keystroke or shot of the camera is going to be genius. All of us only do our best work – the flow – for limited bursts within the total time we spend working.

Art is all about responding to things and processing them, whether it is a deep feeling from within, a compositional puzzle, or like a journalist, responding to current events.

When it comes, it just sort of comes. You can take note of the sort of surroundings and mindset that seems most conducive to the flow – a type of music, a time of day – and try to stimulate that state, but again, don’t force it.

Hannah Beehre, Untitled (Letter Ex Nihilo) 2015 Charcoal and dye on paper

New Zealand artist Hannah Beehre is writing a book about flow, and she has this to say:

“Flow is a peak performance state. It has a particular signature in the brain and is experienced as a moment when work becomes effortless, and we push beyond our perceived limits.

“I’ve spent quite a bit of time researching the state, trying to figure out how to teach it to my students. It’s ultimately about finding a sweet spot between focus and surrender.

“That makes it sound easy, but challenge also plays a role. Adrenaline influences how deep you will go so you want to be pushing yourself too. For me this is the most exciting element, it’s not just about having this lovely experience but change and growth also.

“The other thing I’ve been thinking about more recently is energy. I think it’s best described as a smooth, uninterrupted exchange of energy between yourself, the materials and the idea.

“It’s almost impossible to think yourself into the state. You need to feel it. This makes sense given the type of activity you are activating in the brain. Try imagining your energy located someplace in the space between you and the work. You want to be almost unfocused at either end but present in the middle. Then dial it back so it’s a comfortable level to maintain.

“Anytime you do experience it, take note of what it feels like in your body so you can more easily find it again. There are a myriad of factors which can affect your ability to find it any particular day so be kind to yourself - if it’s not happening and get some work done regardless.”

Take inspiration off that pedestal

Don’t expect inspiration to come from the gods – most people don’t have that kind of brain. A few do, but for the most part, it’s a bunch of Romantic bullshit cooked up in the nineteenth century to get artists and poets laid.

As the late, pre-cancelled American painter Chuck Close said: “Inspiration is for amateurs. The rest of us just show up and get to work. If you wait around for the clouds to part and a bolt of lightning to strike you in the brain, you are not going to make an awful lot of work.”

The reality is that most inspiration is something that emerges from the process of making and thinking, out of the work itself. It sneaks up on you while you’re doing something else. That’s where the ideas are.

Draw, tinker, improvise, look, refocus.

Art is about trying and not giving a flying fart if you fail because there is no failure, only the next step, the next idea. Everything is a possibility or a potential. Be kind to yourself.

That’s what artists have in common with business guru billionaires – the hustle is constant, and no artist has ever panicked at a blank sheet of paper (or screen). They start filling it.

Until next time my lovelies,

Ngā mihi nui

APW XOXO