Life of a village hero

Written by

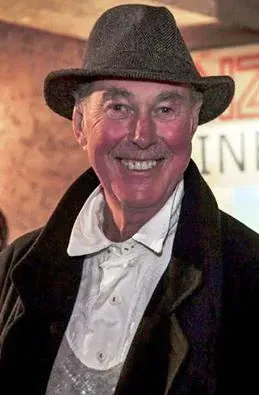

Prolific theatrical performance artist Warwick Broadhead died earlier this year, at the age of 70. His close friend Richard Howard pays tribute to Warwick and his unique, inspirational and highly creative life.

* * *

Between 500 and 600 people attended the funeral of Warwick Broadhead, on 14 January 2015, packing St Matthews in the City to the rafters.

People travelled from all over. The internet and the printed media were alive with messages and images of Warwick; and still they come.

There has been an out-pouring of grief, love and laughter, small wakes have taken place in cafes across the city; there is a huge gap in the lives of many and in the creative community.

During his extraordinary 2½ hr funeral every person stood and applauded, for five minutes in final acclamation of his brilliance as a creator and as a man.

There is talk of memorials and annual events to commemorate him.

Family, friends, colleagues responded to Warwick’s death so fully, because they had been so deeply touched by him, as a huge personality and as a creative genius.

Warwick was the most gifted and prolific theatrical performance artist in this country for decades – with more than 50 productions and thousands of performances to his credit across his 70 year life.

His were highly creative original works; conceived, scripted and directed by himself. Thousands of people performed in and helped produce his shows, in settings as diverse as the old Auckland Railway Station, parks, beaches, warehouses, studios, the streets, private homes and occasionally even a theatre.

Participation in a Warwick Broadhead production was for most a revelation, a life altering, developing experience.

The performances were seldom perfect examples of professional theatre as traditionally accepted; sometimes they barely hung together at all. They demanded that you engage and struggle to make meaning; they were always extraordinary creations.

You would go to the mainstream theatre for the reworking of an old favourite or maybe for a new piece of formalised work; you would go to a Warwick Broadhead production to be blown away by extraordinary imagery, ideas and feelings and wonderment – you didn’t always understand what was going on in a conscious sense; not dissimilar to a weird kind of opera in a foreign language.

The work and his life did not seem to be driven by an overt agenda or philosophy; both seemed to be responses to ideas and experiences percolating in his brain in the present or over many years.

For most people, including many in theatre and arts circles, Warwick’s work would barely register on the radar; Warwick explored and occupied the nooks and crannies of his local and international environments, of the creative and spiritual worlds, of world cultures, community and psyche. They were as hard to define as it is define Warwick and his life.

Numerous deeper constant dynamics were nevertheless discernible – the notions of impermanence, revelations of invisible influences, in direct challenges to codified patterns of thinking and behaving, expression of heart and beauty.

Where there was a recognisable story line it would often be broadly interpreted, subjugated to the sense, the mood, the imagery and notions that Warwick would thoughtfully apply.

By its nature the work and Warwick himself contrasted to New Zealand blokey culture, conservative culture and lifestyle. He was a champion of difference, possibility, colour, of obscure nuance and of the invisible.

The creative brilliance of the man permeated and reflected brightly in almost all aspects of his life – art was not separated from daily life.

Warwick’s strength (and weakness) was that he loved to perform, to be in the spotlight, to win the attention and the adoration – and he did right to the very end of his life and beyond in fact.

His homes, furnishings and dress and his few Spartan belongings were made by his own hand.

It would be difficult to find anyone else who so completely manifested each moment of their life, so uniquely, who maintained such a degree of personal discipline and daily practices for their body and mind and spirit – he was a constant inspiration.

Few would have met Warwick without being affected by his continual playfulness, his eccentricity, his personal or creative challenges, and his capacity to turn the mundane moment into something fun or extraordinary. Time spent with Warwick was often transformational.

With such intense brilliance came the converse, the deep inner struggles, compulsive attention seeking and eruptions of funny and or shocking behaviour. Nevertheless Warwick died at peace with himself and with the great mystery of death.

Warwick produced his work to be directly experienced by his audience and then left to linger in their hearts and minds - there is very little in the way of archived material. His legacy resides in the hearts and minds of the many people who knew him or encountered his work.

He chose obscurity and an expression of impermanence for his epitaph as well, being buried in an unmarked grave.

Loved, appreciated and remembered by many.

- Richard Howard

Glimpses of Warwick’s style of work can be seen in the film directed and produced by film maker Florian Habicht – Rubbings from a Live Man.