Making Aotearoa's Taonga "Last Forever"

Written by

Any museum worth its salt needs two things to function.

The first thing is pretty obvious - things of cultural value and significance. Items, artworks and artefacts that spark imagination, that display the history of the generations that have gone by - and the one we’re in right now.

Auckland Museum’s Anika Klee doesn’t have any hesitation when declaring the other non-negotiable element.

“A museum is not a museum without people,” she enthuses. “The impact that we can have is amazing, being able to share these extraordinary things with people, we’re very privileged.”

But this essential relationship comes with one catch - sometimes, it’s those who come through the door that pose the biggest risk to what’s inside.

If a museum is nothing without its manuhiri (guests), the same can be said for its collection of priceless taonga. Which is where Klee comes in.

As a Senior Collection Manager, she’s part of the Collection Care team that ensures the experience you have inside Auckland Museum leaves a lasting impression on you - but that impression is not left on what you came to see.

“It’s definitely a team effort to take care of everything. We’re continually trying to get the taonga to last as long as possible.”

And by as long as possible, Klee affirms “we’re trying to keep these things forever.”

Kaitiaki of our taonga

Easier said than done - especially as Auckland Museum is kaitiaki (guardian) for more than 4.5 million objects in its various collections, from tiny flakes of stone to large wharenui (meeting house).

That doesn’t even include having the duty of condition reporting for visiting exhibits like ‘Peter’ - the imposing 12 metre long Tyrannosaurus Rex currently making eyes pop during a five month stay.

Photo: Auckland Museum.

Klee details “Peter came in several crates - each piece is taken out and photographed so we can check if there are any changes. It means we can say ‘this is how he came in, and this is how he went back.’”

Both protecting and sharing items that can be centuries old may sound like a daunting challenge but it’s one that Klee relishes.

Klee explains “the Collection Care team is highly trained in handling objects, to look for weak points. For example, in a museum you’d never pick up a cup by its handle.

“We’re also trained in how to mitigate against the ten agents of deterioration - light, incorrect relative humidity, incorrect temperature, pests, disassociation, water, fire, theft, physical forces and pollutants.”

Photo: Auckland Museum.

With great responsibility comes much care. Items can’t be on display in the museum galleries for too long before they start to fade under the lights - natural or artificial.

It’s a constant balance between the desire to display and the need to protect.

Touchy subject

And that’s where we come in as manuhiri. We too have a role to play as kaitiaki.

Let’s be honest - how many people have touched something out of sheer curiosity, despite a sign that explicitly states not to do so?

While some items are displayed in perspex or hoisted high above the ground, Klee outlines the importance of letting our eyes - not our fingers - do the exploring.

Photo: Auckland Museum.

“Our hands are generally not the cleanest things, we’ve got oils that cover them - a lot of that gets deposited on the object when you touch it. Over time, the more people touch something, the more it wears down.

“When I was in Cambodia, you could see where so many people had touched the temples that it started to get shiny - it’s amazing when you think about that even rock can be worn away just by touching it with our hands.

“The less an object is touched, the less risk there is of damaging our taonga.”

Food for thought

There’s another sign many of us are guilty of ignoring.

Being told not to eat in certain parts of the museums may feel a little pedantic - especially for those corralling young children at the same time - but the reason goes far beyond cleanliness.

“A lot of our collection is made up of fibres and natural materials that are very tasty to a variety of insects and rodents,” Klee details.

“One of the things that we use to protect our collection against them is an Integrated Pest Management Plan. Big fancy words that mean that we’re basically trying to deter these insects and rodents from entering the museum in the first place.

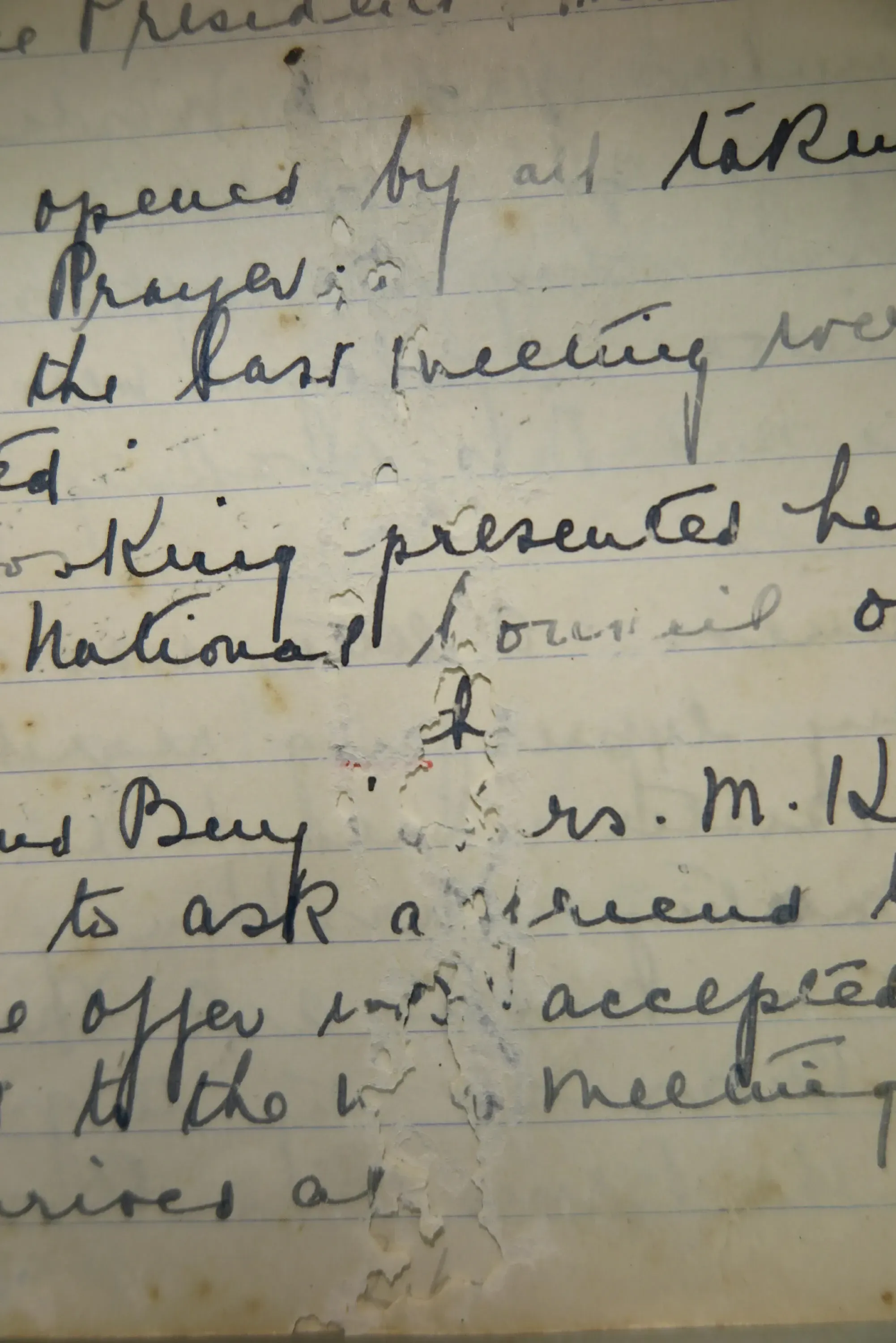

Example of what silverfish can do to old manuscripts. Photo: Auckland Museum.

“So the fewer things that smell or taste nice that are available to them, the less likely they are going to munch on our collection. They don’t see a difference between a crumb on the floor or an object made of fibre.

“We want people to feel comfortable - that’s why we have food zones, the Grand Foyer and Te Ao Mārama (South Atrium) to sit down, rest and eat and drink. We just want to keep the galleries clear of food so we don’t invite in all those creepy crawlies that might be a problem.”

Surprises in store

Photo: Auckland Museum.

While it can be a reactive role, Klee and her colleagues aren’t just looking after these items right now, they’re planning for their future - that’s the ‘forever’ part.

“This museum is full of surprises - because we’re constantly changing out displays, there’s always something new to see.

“My work is a lot of problem solving, which definitely involves a lot of creative thinking. Storage is one of those things people don’t think much of but if you have an object on a table and then have to figure out how to store it, it can be quite a creative endeavour.

“Our team has devised these really unique storage solutions - we have light aluminium crates with open sides so you can see and move the object without touching it, which is ideal.”

It’s that behind-the-scenes work that opens up so many windows of wonder - these items may be ancient, but the thrill never gets old for Klee.

“Most museum workers feel that we’re in a very privileged position. There’s so much here, and there’s so much that we get to see every day that isn’t available to the general public.

“We’ve been collecting for over 150 years - we work on these projects one collection at a time with digitisation and cataloguing (including the online collection), to improve things and make our collections more accessible for exhibitions and the public.”

Photo: Auckland Museum.

Again, this is no small feat. Auckland Museum currently has 40 collection stores, including small stores inside larger ones such as cool stores and arms stores.

“We can’t physically put everything on display - there’s not the space - we’re trying to get more things out on display as much as possible.”

But even the collections that aren’t out on show can still make their mark on the creative community.

Klee illustrates “we often get artists visiting us to look through our collections, to get inspiration or to research how things were done in the past.

“It’s one of the privileged things we get to do, opening all these boxes to show people what’s inside them. Until someone requests to see something, we may not have ever seen it for ourselves so it can be a discovery for both parties at the same time.”

That includes author Claire Regnault, who spent time examining clothing items in the history collection for her Ockham non-fiction prize winning Dressed and photographer KT Ho as he prepared for an exhibition in honour of the history of Chinese migration to New Zealand.

So the next time you walk around a museum and admire the immaculately preserved exhibits, know that your role as both a visitor and a kaitiaki is never taken for granted.

Written in partnership with Auckland Museum.