More than Words: The Great Human Canon

Written by

Nina Finigan is the Curator of Manuscripts at Auckland Museum. Last year, a public call-out resulted in hundreds of submissions of personal communication that ranged from letters and scribbled notes to Facebook messages and emails that have been loaned to the Museum. They share pride of place alongside items from the Museum's manuscript collection in the new exhibition Love & Loss - which Finigan declares is worth far more than the paper they're written on.

We are all storytellers.

Every day, we tell our stories in myriad ways. And when we commit pen to paper or finger to key - when we write a letter or even send a text - our stories take concrete form.

This is our great canon. Not just the realm of poets or great writers, this canon belongs to all of us - our collective story.

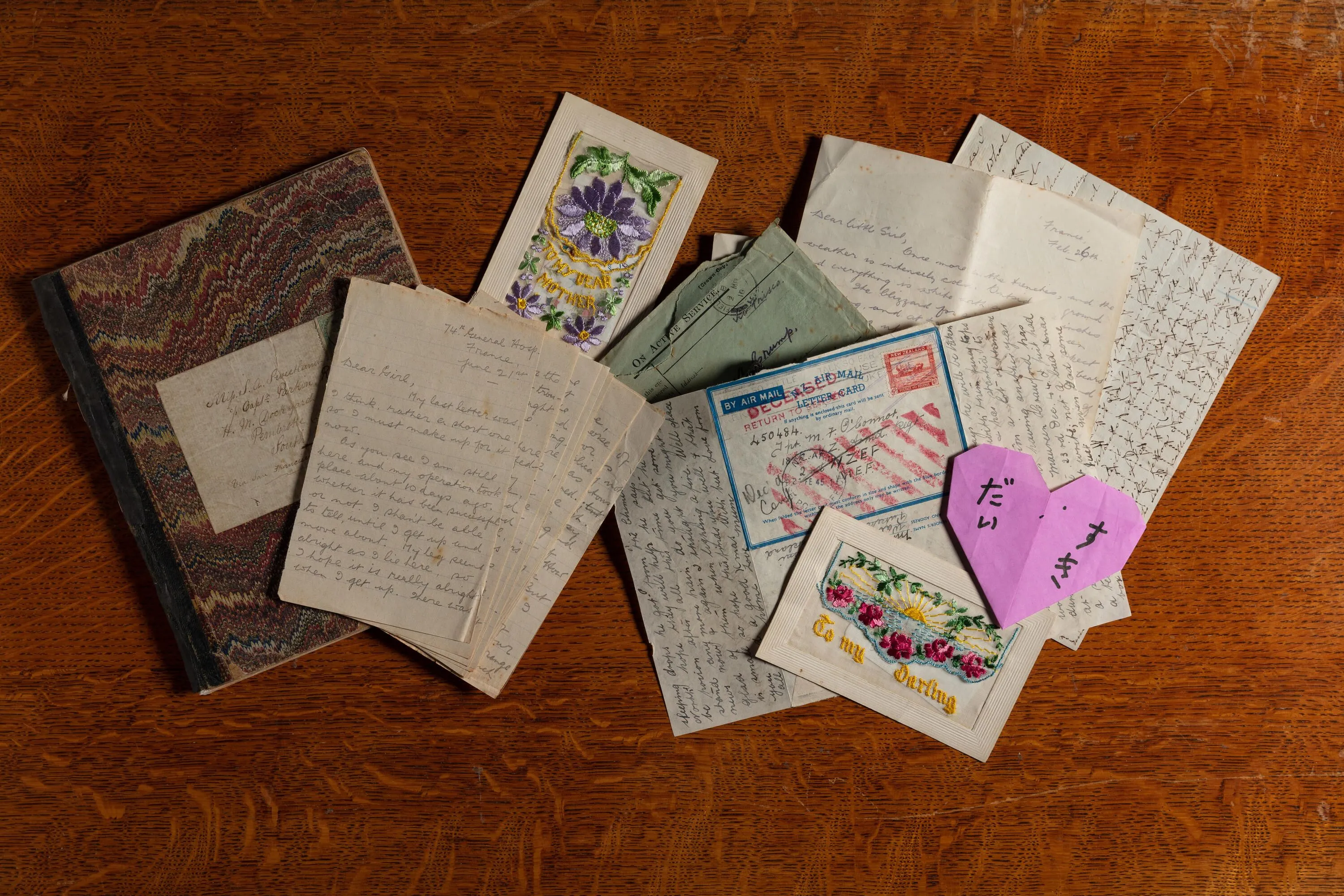

Love & Loss, a new exhibition at Auckland Museum, seeks to reframe the documentary traces of our lives - letters, notes, messages and texts - as sacred spaces, as artifacts that carry the fingerprints of our lives and relationships, and as relics that reveal something profound and beautiful about what it means to be human.

In the museum sector, we call collections of documents like these ‘archives.’

Emotion, love, grief and longing might not be what comes to mind when you hear this word. As a curator who works with these collections, a mention of ‘archives’ is often met with words like dusty or boring. This narrative is bolstered by the histories of collecting within our institutions - collections amassed not necessarily because they exist in their own right but because they help illustrate larger narratives about conflict, or migration, or life in Aotearoa.

Photo: Auckland Museum.

But what happens when you strip those larger narratives away? What we find is people telling their stories - their lives and loves forever immortalised within the two-dimensional world of a letter.

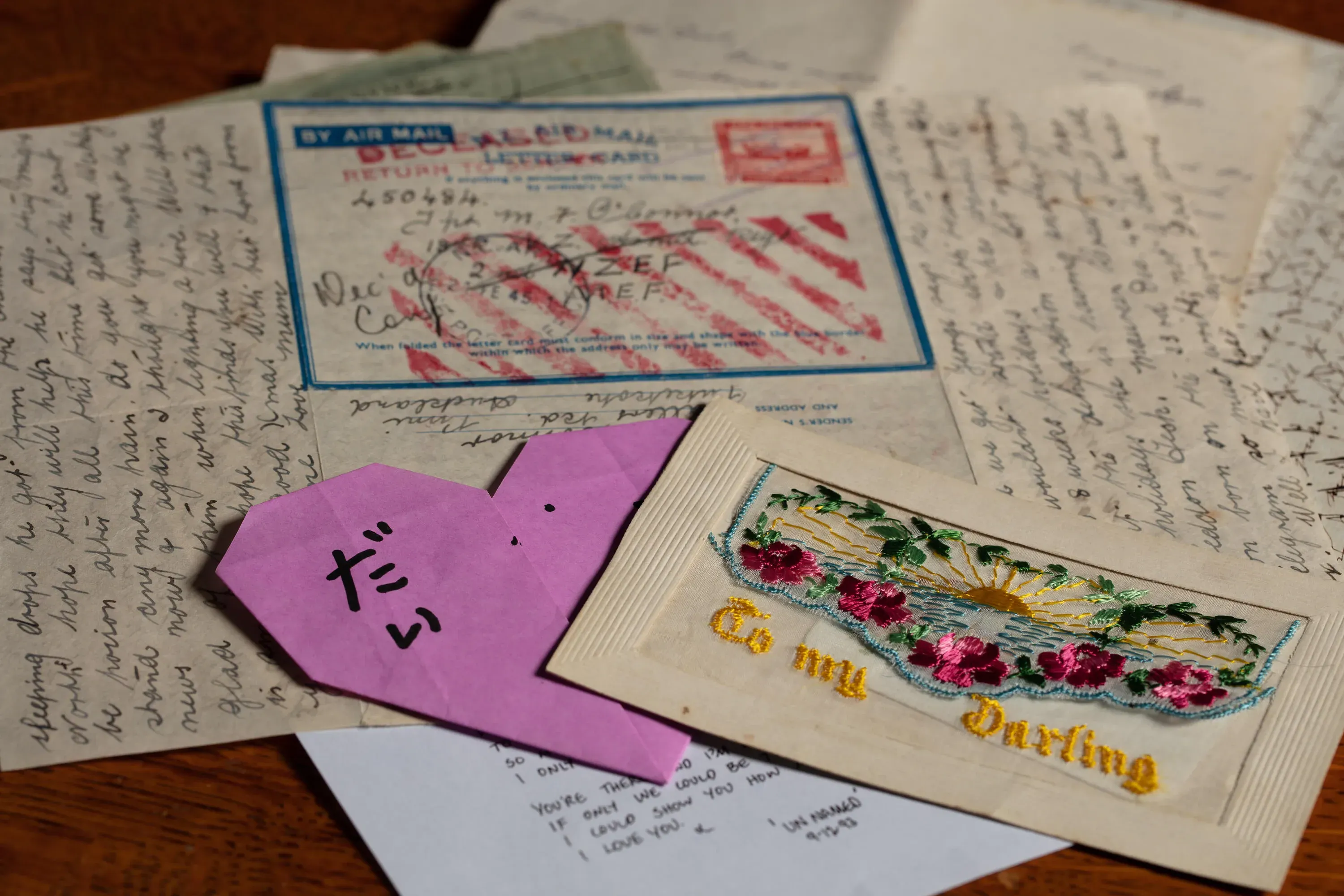

In 1915, Richard Tukino Grace went to Edinburgh to study medicine. Not long after, he joined the 16th Royal Scots Battalion and thus entered the war.

At home in Aotearoa was his sweetheart, Alice Crump. As Dick moved across the war torn landscape of the Western Front, he wrote regularly to Alice - of what he saw around him, the people he met and the devastation he encountered.

His correspondence however is much more than just observational missives - they are love letters. From the pages of his letters, Dick writes vividly and lovingly to Alice, recalling their past and imagining their future.

His letters are spaces of magic and imagination, allowing him to transport himself back home to her. Writing as if he is next to Alice, he places himself in her drawing room, observing her hair gleaming in the firelight, or on a walk together among the the familiar flora of home:

...as I was saying before, Alice, it would be beautiful to be back with you – away from this feverish and unnatural existence, to walk out along the county road on a fine warm day of sunshine, or go for a little scramble in the bush.

There I would see the familiar ferns, the wild berries and the well known bush mould under the thick tangle of undergrowth. The fine big tawas, the birch, the rimus and the supplejack and other creeping vines, all would be beautiful on a fine day with their warm tints which one never sees in these colder countries ... To see that all again, and be back with you, is a great longing, Alice.

Within this two-dimensional world, past, present and future are woven together and the space between Alice and Dick collapses.

Although entirely unique, there is a universality to this love story.

Photo: Auckland Museum.

It’s one that hasn’t changed much - our need to reach across oceans to each other, to seek platforms that allow communion with those we are far from, and the centrality of the written word in this relationship remains consistent.

And thus we tell our stories and they take their place alongside all the others.

The great human canon.