Ōriwa Haddon - Under-Appreciated Artist

An extraordinary art exhibition in the most unexpected place. Upstairs in the corridors and rooms of the Havelock Pub.

Where? Havelock – it’s a small town at the very head of Pelorus Sound, on State Highway 6, halfway between Picton and Nelson.

Like so many New Zealand small towns, Havelock needs something big. So it proclaims itself ‘the mussel capital of the world.’ And indeed, the mussel barges own the channel to the harbour, the mussel factories hum day and night, puffing out random white smoke signals, heavy mussel trucks wheelspin and churn up the smooth new tarmac just laid in the main drag.

And the entire town is littered with larger-than-life fibreglass mussels, which eyeball you with cartoon eyes from rooftops and knee-height from the curb. It’s all a bit weird – but in the nicest possible way.

And tucked away upstairs at the pub, is a collection of paintings by the little-known, but should-be-more-so, folk art painter Ōriwa Haddon. Perhaps he’s the other big thing about Havelock.

Towards the end of his rich and full life, it appears Ōriwa Tahupōtiki Haddon (not his birth name) was something of an itinerant travelling painter, often paying for lodgings at country pubs and marae by way of offering his paintings instead of hard cash. While his wife and eleven children made do elsewhere.

But hang on! If this is the case, surely there are other places where Ōriwa left his work?

Yes. Try the Havelock Town Hall directly across the main street, the Canvastown Hall up the road a wee ways, Waikawa Marae, the Golden Bay Museum at Takaka, the Founders Heritage Park Museum Nelson, the Marlborough Museum, and Aotea Utanganui the Museum at South Taranaki.

Mostly the museums have salvaged works from pubs past that were facing demolition. And there must be more out there.

But it took a long and winding road to get this far.

Son of a preacher man

Edward Oliver Haddon was born at Waitōtara, South Taranaki, on 7 November 1898, the eldest son of a Māori Methodist minister, Robert Tahupōtiki Haddon of Ngāti Ruanui, and his wife, Huihana (Susan) Haerehau Shelford of Hokianga.

We get the basics of his busy biography from the Te Ara website: “Tahupōtiki Haddon had been trained in traditional knowledge by his relative Tohu Kākahi of Parihaka, but through the influence of the Methodist missionary T. G. Hammond had entered the Methodist ministry. Through Oliver’s early life, Tahupōtiki ministered to Māori in South Taranaki, seeking to reconcile them to Christianity and to Pākehā. Oliver attended school at Ōkaiawa and Normanby, and entered Wesley College at Three Kings, Auckland, in 1914.”

Then, around 1919 he and whānau went to the United States to be part of a cultural tour - concert and lectures – travelling that nation as part of the Chautauqua and Lyceum circuits. They presented an odd mix of lectures, theatre and vaudeville entertainment. Oliver lectured on Māori life and customs. “On 12 September 1920 at Billings, Montana, he married the talented pianist in the concert party, Ruihi Moringa (Marianga) Reupena of Whanganui. They were to have four sons.”

In the States, Haddon is understood to have done a course in industrial pharmacy. Returning to New Zealand, he “may have practised briefly in Whanganui as a chemist, but his career soon took a different turn.”

The Methodist ministry took him in on probation in 1922, as he intended to go as a missionary to the Solomon Islands. But Moringa’s ill health meant that they were instead stationed at Gonville in Whanganui in 1925, with a focus on Māori ministry.

Here his story takes on extraordinary acceleration:

“Moringa died at Pūtiki on 4 February 1926, and on 16 February, at Whanganui, Oliver married Maaki Rakapa Taiaroa of Ngāi Tahu. The marriage was arranged to join Ngāti Ruanui and Ngāi Tahu in kinship. Oliver and Maaki were to have four daughters and three sons. Oliver was appointed missioner to Kawakawa in 1926.”

By 1927, his father Tahupōtiki Haddon, was recognised as the senior Methodist Māori minister. And he was “permitted to retain links with the Rātana church despite growing hostility from other denominations.” He sent Oliver and Maaki to Rātana pā, with responsibility for running the school there.

Multi-disciplinary Pinoneer

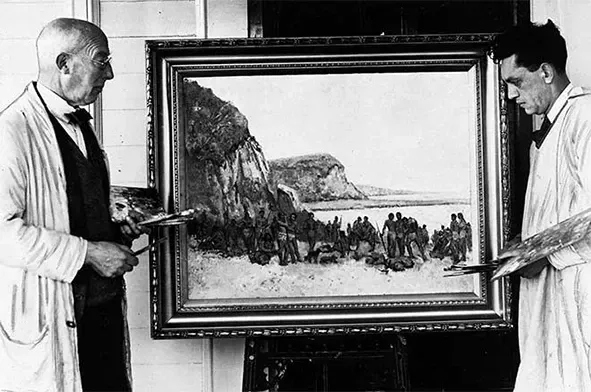

Oriwa Haddon (right) 1933 with Charles Duncan Hay-Campbell painting arrival of Turi at Pātea. Photo: Supplied.

Now calling himself Ōriwa Tahupōtiki Haddon, he also built a reputation as an artist.

‘Our 1929 discovery’ said Pat Lawlor in the New Zealand Artists Annual, who published Ōriwa’s illustrated story Tiki of the dawn. Ōriwa was then commissioned by the Taranaki Māori Trust Board in 1933 to paint the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi. The painting was presented to the governor general, Lord Bledisloe, in 1934 and hung in the Treaty House at Waitangi. The original appears to be ‘misplaced’* by the Treaty House, though they do have a reproduction.

The Methodist contacts were again in effect - when church minister Colin Scrimgeour became controller of the National Commercial Broadcasting Service in 1936, Ōriwa got a job at radio station 2ZB in Wellington – part of a campaign by Scrimgeour to introduce Māori broadcasters.

Haddon had his own programme, Ōriwa’s Māori Session, and also made contributions to others and to 5ZB - the travelling station, which broadcast from a customised railway carriage.

Ōwira Haddon and Ana Hato, 1940. Photo: Supplied.

During the Second World War, Ōriwa enlisted in the air force. He travelled to the Pacific Islands, and kept on painting and singing. His painting Māori mythology appeared in the 1944 New Zealand Artists in Uniform exhibition, and a pen and ink work, Hine Kohu and Uenuku, was included in the National Centennial Exhibition of New Zealand Art in 1940.

Then he found work from the Department of Tourist and Health Resorts and Publicity to produce oil paintings for the centennial celebrations. He also contributed illustrations to other publications.

On top of all this, Ōriwa Haddon was also involved with Labour Party politics. In 1934 he was among Māori Labour supporters who tried to start a national Māori newspaper. With his return to civilian life after the war, he joined a group of Labour-allied Rātana MPs in the preparation of what became the Māori Social and Economic Advancement Act 1945. He also became dominion organising secretary of the Labour Party’s Māori Advisory Council and edited their publication, The Māori way of life (1946). Says Te Ara, “This position took him all over New Zealand, and his renown as an orator on the marae served him in good stead.”

But in 1948, Ōriwa broke up with the Rātana MPs and left the Labour Party. He reckoned the Rātana movement was falling apart and that Labour had hardly done much for its Māori members. He moved to set up an independent Māori political party outside of Rātana, but found little traction.

So he retired from politics and moved to Nelson, living on commissions as a painter.

Nelson impression

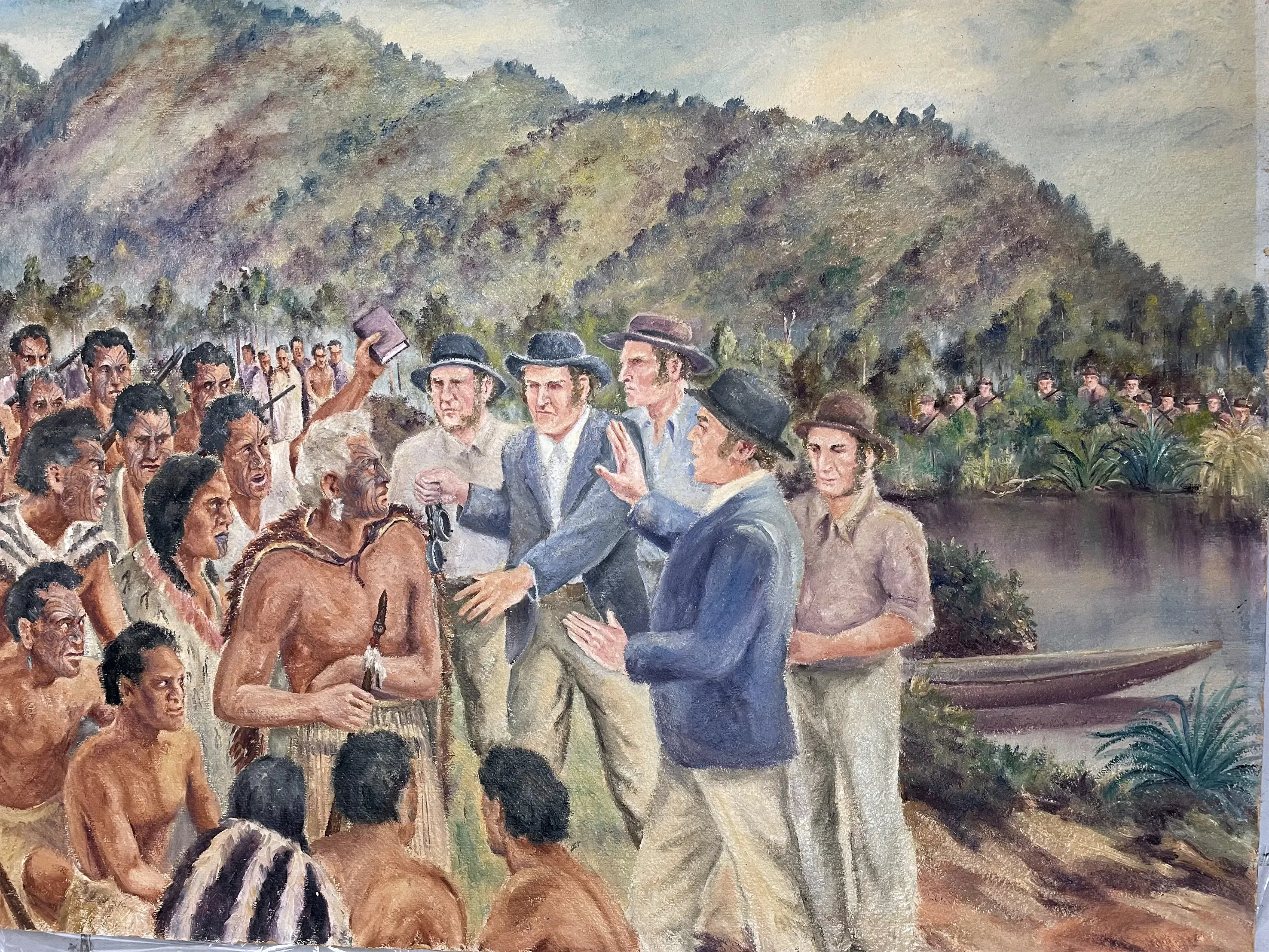

He completed a series of eight paintings for the Commercial Hotel, Blenheim. These included scenes depicting local history from Cook’s landing to his present. A centrepiece showed the attempted arrest of Te Rauparaha at Tuamarina, as part of the Wairau Affray in 1843.

Ōriwa Haddon, The Wairau Affray, Marlborough Museum, MHS Collection. Image: Supplied.

AH Reed, the pioneering New Zealand publisher was also something of a peripatetic fellow. He literally walked the country flat; and recorded his footslogging adventures in a series of books. In Marlborough Journey he mentions meeting Ōriwa Haddon. If they met around a fireplace, indoors or out, I would love to have been a sandfly on the wall of that conversation. I reckon there’s a lovely short story in that!

Ōriwa almost slowed down when he retired to Utiku, just south of Taihape, where he painted murals on commission for the local Returned Services’ Association.

Te Ara wraps up his life story: “He died at Taihape on 17 June 1958 after a car accident, and was buried in the Māori cemetery at Ōkaiawa, Taranaki. He was survived by his second wife, who had not accompanied her husband on his numerous escapades, and eleven children.”

Rediscovering Haddon

But his art lives on.

Steve Austin, Director of Marlborough Museum in Blenheim is a serious fan of Ōriwa’s work.

“It’s important that we raise his profile. Haddon is really interesting partly because of his life before his career as an artist, and the life of his work after his death..

“He was very expert at conveying aspects of Māori culture – through performance, radio and painting. It all adds up to a significant body of work, and one with a distinctive context.

“He’s probably due for a book.”

Marlborough Museum has a number of Ōriwa’s paintings – on display and undergoing conservation work.

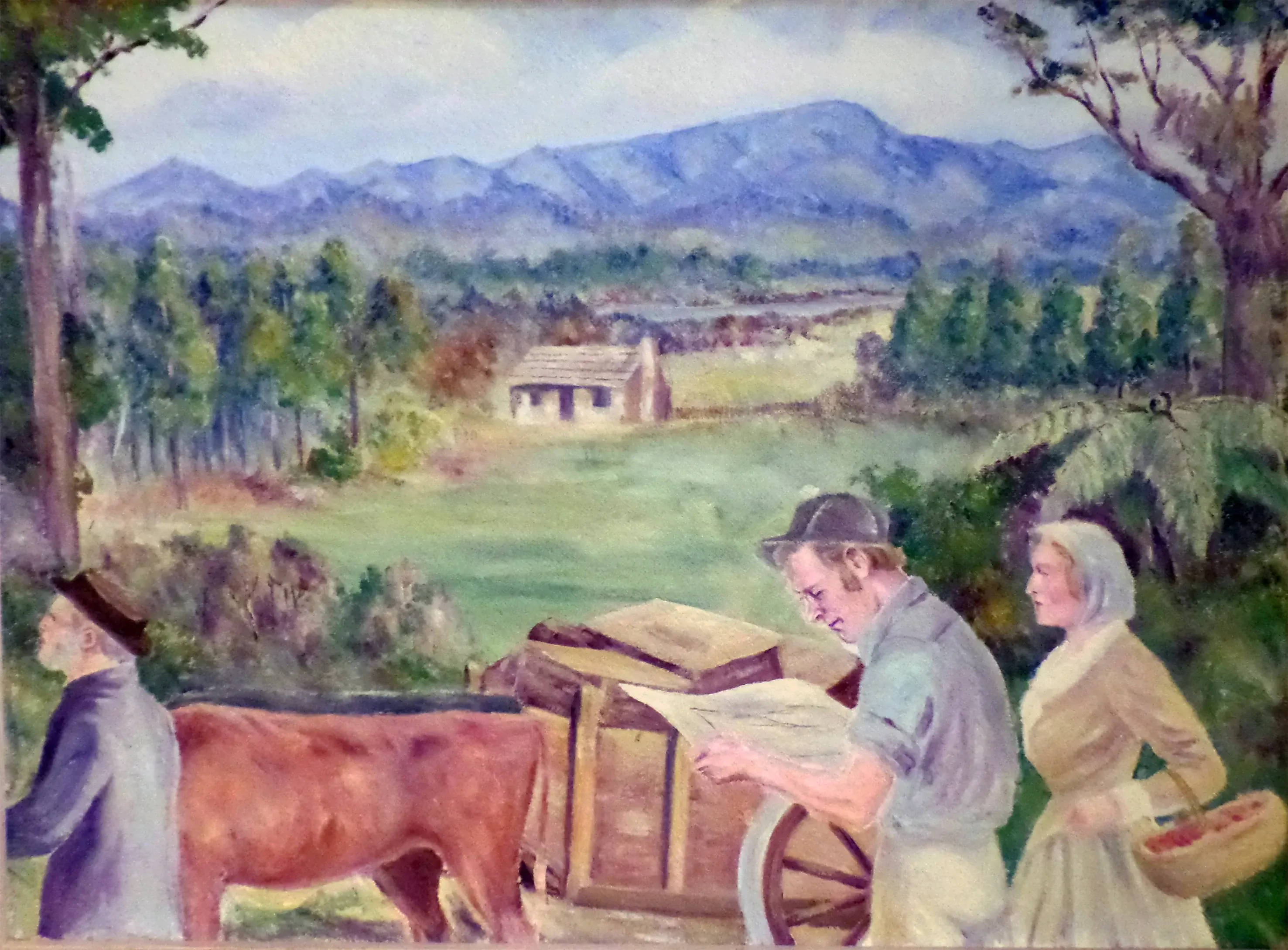

Ōriwa Haddon, Settler, Marlborough Museum, MHS Collection. Image: Supplied.

But look a bit further, and you’ll find Ōriwa Haddon’s paintings in a number of other unlikely places. This standing gallery of his oeuvre is kinda like a passport to out-of-the-way New Zealand. The wallpaper of the wop wops.

In the new national sport of New Zealand – that of Kiwis re-discovering our own country in the post-COVID world - a road trip seeking out Ōriwa’s paintings may be just the ticket. A real-world art-themed discovery of out-of-the-way delights.

Austin reckons that Ōriwa should be better-known, for he holds this pivotal place in our art and cultural history.

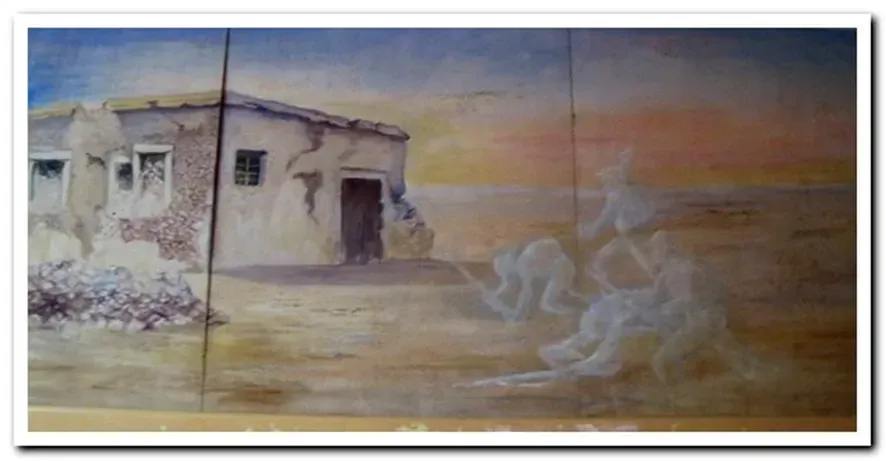

Ōwira Haddon, Bush mural at Canvastown Hall. Photo: Supplied.

“He lived through the time of urban drift for Māori; walked in two worlds; and interpreted aspects of Māori culture to new audiences through different media at a time when the question of what it meant to be Māori and a New Zealander, in the modern world, was challenging.

“His style and palette are very much of 1950s America.” But his vision is authentic as New Zealand-real.

Austin is interested in how Ōriwa sourced his art materials and imagery. It is thought that a brewery company paid for his artist’s oil paints – that would be an interesting angle on our history of art patronage.

For people embarking on a journey of discovery such as this, getting in touch with other like-minded folk is an important place to start. There’s now a Facebook page dedicated to Ōriwa Haddon. Connections can be made from there.

Aotea Utanganui the Museum of South Taranaki has devoted a comprehensive page on their website to him.

Especially interesting is the writing of art conservator Caroline Izzo, on the challenges of holding on to this visual taonga:

“These 10 panels, [salvaged from the Commercial Hotel Hawera demolition] located at Aotea Utanganui, are generally in poor condition. The Pinex supports present visible damages caused by natural degradation of the materials, inadequate past transportation, inadequate hanging system, graffiti and wrong use of the panels (used as a dartboard).” The emphasis is mine.

In a newsletter to supporters of the Havelock Museum, Linden Armstrong wrote, “Judith Taylor, who works for Te Papa National Services keeps an eye on small Museums in the South Island. She came to take photos of all the Ōriwa Haddon paintings for conservation advice. Judith took photos of each blemish separately, there are many holes, scratches, water marks, alcohol spray and years of smoke damage.”

It's clear that Haddon’s work has survived (had to survive) outside the hermetically-sealed world of museums. In this way, his work has always been for the people, community and place, and in many ways this contributes to his appeal today.

Austin echoes these conservation concerns: “The Pinex, a kind of cheap early particle board, disintegrates with moisture, but is also brittle, and highly flammable. And is extremely acidic as a substrate for the paintings.

“We have enough in the way of challenges just locating all of Ōriwa’s existing paintings – let alone finding funding to conserve them (clean and stabilise them) as well as physically protect them.”

We started with an extra-ordinary art exhibition in the most unexpected place. Make that many places, plural. Which, perhaps, makes it even more special.

Austin is right: It’s time we all knew more about Ōriwa Haddon.

Gone missing

The Missing Waitangi House painting. Photo: Supplied.

A story as rich as Ōriwa’s must, by rights, also include a whodunnit sidebar. Here it is: a painting of his, gifted to the Waitangi House, has simply disappeared. But not the ornate carved frame it came in.

Caitlin Timmer-Arends, the Curatorial manager at Waitangi House writes, “We did once hold a painting by Ōriwa Haddon, it was painted and gifted to the Waitangi National Trust in 1934 and formed part of the ‘establishment gifts’ subset of our heritage collection.

“It was gifted in a frame carved by Thomas Heberley and displayed in the Treaty House for many decades. The official recording of the gift is ‘given by the Māori Tribes of the Taranaki via the Taranaki Māori Trust Board’.

“For a fair amount of time, Waitangi did not employ a curator and brought in contractors approximately every 10-15 years to audit the collection. At some point between the 1974 and 1989 audits the painting was removed from the frame, and recorded as missing in the 1989 audit.

“I don’t know the circumstances behind the painting being missing, i.e. whether it was stolen, or whether it was given to someone by a member of staff or member of the Waitangi National Trust Board.”

The plot thickens! The art heist unsolved. The thief, or the borrower, got away with it.

A photocopy of the painting is in the original frame, now on display in Te Kōngahu Museum of Waitangi’s permanent exhibition Ko Waitangi Tēnei: This is Waitangi.