'Pop Life' at Tate Modern

Written by

James Hadley in London visits Pop Life - Art in a Material World at Tate Modern and describes how the art was so challenging it created a ‘self conscious spectatorship’ experience similar to immersive theatre.

Hadley says it highlights how art forms are merging in interdisciplinary ways “to intensify the viewer’s engagement in a creative experience.”

* * *

I've heard of art exhibitions of the past where ‘anyone who was anyone’ would go to be seen engaging with the shock of the new. But until now I've never felt like I was attending such a spectacle; where the crowds of beautiful young things and urbane culture vultures make it more like going to a nightclub than an art gallery, and the art was so challenging that your self-conscious spectatorship turns the whole event into one big theatre event in many ways.

The Tate Modern gallery on London's South Bank is one of the most highly visited galleries in the world - and London's most visited attraction. But my visits there have often left me underwhelmed. Its new exhibition, Pop Life - Art in a Material World, is the first time I've felt the gallery justified its crowds. The collection of art on display is curated around the concept of artists from the 1980s who have cultivated their own brands through their interaction with consumerism, from Andy Warhol's late dalliances with celebrity culture onwards. While this was a visual art exhibition, there was a blurring of art and life within several of the exhibits that led me to read much of the exhibition as an immersive theatre event.

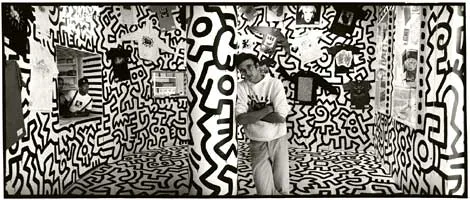

For example, one room of the exhibition had been turned into a recreation of Keith Haring's Pop Shop, where he challenged notions of art only being available to the rich by selling merchandise featuring his designs at high street prices. This room in the gallery was decorated in Haring's distinctive linear graffiti, with 1980s rap and house music playing, and merchandise on the walls which you could then wander over to the counter and purchase. In buying some badges I felt I was participating in a performance installation; a symbolic act of purchasing mass produced art within a gallery setting that would usually uphold the notion that the art I was viewing was effectively priceless to someone with my sort of income.

Then there was the pair of dot paintings by Damien Hirst that are always exhibited with a pair of real life identical twins. The twins are named on the wall placard as if they were exhibits themselves, and effectively they are, so I guess it's performance art, of a type. What's strange is that these are just members of the public who have answered the artist's advert and are being paid to sit beside each other, dressed identically and with identical hair cuts. I have never seen twins as identical as the two who were on display when I was there, and I have to say (being a keen people-watcher in life) there was something thrilling about being given permission to just stare at these two individuals.

I suppose it's no different to buying your theatre ticket in order to watch the actors onstage, but this was fundamentally different too. They weren't performing, even when they both started playing with a Rubik's Cube simultaneously, as presumably directed by the artist. There was a formal echo visually between the two of them and the two paintings behind them - while living human individuals, what was most important about them within the context was their role as symbolic signifiers of visual duality. Perhaps it was a bit like a freak-show spectatorship dynamic. Certainly this is the case with the artist's artworks of dead animals preserved in formaldehyde in glass cases - on the other side of the wall behind the twins was a preserved white calf with gold plated hooves, floating there in permanent limbo. I'm glad the human twins were instead displayed alive and co-existing in our own space. It was curious watching some viewers strike up conversation with the twins, partly out of feeling it was a bit rude to just stare at them without saying anything.

Some of the exhibits had gained a commercial brand through the artists' efforts to shock. In this day and age, we tend to think of ourselves as rather hard to shock, but when I wandered into a room to find a dead horse pierced in the side with a placard bearing the inscription 'INRI' (the same sign you find in images of Christ's crucifixion, meaning 'here is the king of the Jews'), I have to admit I was rather shocked. And when you're genuinely shocked by an image or object, you become aware of your viewing it in a public space alongside others - how do their responses differ from yours? So it becomes a great deal more like a theatre spectatorship dynamic. (The work is by the artist Maurizio Cattelan).

And as if in proof of the exhibition's edgy status, one of the room's was cordoned off - closed from public access since police visited and deemed it as making the gallery liable to obscenity charges if they continued to allow public access. What was previously displayed within this room was a copy of a photograph of a 10 year old naked Brooke Shields, wearing heavy makeup so that it made this then child actor appear like a sexualised adult. The reproduction of the photo by Richard Prince was entitled 'Spiritual America' - perhaps the fact that no-one can now access this work makes for more interesting commentary.

But this isn't to suggest that the gallery attendee is spared explicit content; several rooms in the exhibition have an R18 restriction. One of them is filled with works from Jeff Koons' Made in Heaven series. These works depicted the artist having sexual intercourse with his wife, a porn star - wherever you turned in this room you were confronted with explicit imagery including a close-up image of genital penetration such as would only ever be depicted in a pornographic context. Yet as viewers we're immediately asked to rethink our reading of these images. It feels odd to be viewing what most would term pornography in a public space. Viewing a larger than life-size sculpture of the artist penetrating his wife which left nothing to the imagination, I couldn't help trying to avoid making eye contact with the elderly lady viewing it from the other side... Yet one of the provocations set by these works is: what's improper about images of a married couple making love?

Yet again it felt very much like a performance installation. The gallery attendant letting viewers into the room, checking their age at the door, and spectators visibly taken aback by being confronted with such large-scale images of explicit sexual acts as they entered the room. More than the works themselves, it was the act of viewing the works, in full daylight, alongside other viewers, that felt like the most provocative aspect - did you feel comfortable viewing explicit images of sex between a married couple in public, and what were the social/moral/religious reasons at play behind any sense of impropriety to the dynamic.

Similar questions about public attitudes to sex were asked by the works of Cosey Fanni Tutti and Andrea Fraser, who sold their bodies to pornographic magazine photographers and to the first man willing to pay her asking price and be filmed in the act, respectively. The end products are on display here, again distinguished from actually being porn only by the frame that the artists have placed around their acts, which comment upon them, and ideally distance us to read them in new ways within the art gallery context. The act of looking at such works is heavily self-conscious for most - after all, you have a museum attendant scrutinising the spectators continually to ensure no inappropriate behaviour or underage viewers sneak into the equation. The exhibition is also so full to the brim with spectators that it's like being on the Tube in rush hour, so its constantly an act of collective viewing - just as in the theatre.

I couldn't help thinking back to my experience of Punchdrunk's last show, 'It Felt Like A Kiss', earlier this year at the Manchester International Festival. That was very similarly a succession of rooms through which we viewers wandered, immersing ourselves in installations, viewing footage and looking at static images, and occasionally being given guidance on what was appropriate viewing practice. There's very little distinction between that immersive theatre show and this art exhibition. It was one in a growing list of experiences that highlight the degree to which many artforms are merging in different interdisciplinary ways to intensify the viewer's engagement in a creative experience.

Image: Keith Haring, Pop Shop, © Keith Haring artwork, © Estate of Keith Haring. Photo: Charles Dolfi-Michels