"Powerful, Playful, Joyous"

The “biggest and baddest” contemporary art puts New Zealand on the international art map - so how do you make it feel more accessible?

Written by

How do you make contemporary art feel contemporary?

In the eyes of Auckland Art Gallery (AAG), it appears you double down - and the initial result is a major success.

The launch of AAG's cornerstone showpiece - the triennial (formerly biennial) Walters Prize 2024 - alongside a new triennial, Aotearoa Contemporary was intriguing to watch in action.

The two exhibitions are discreet; The Walters is a 25-year-strong prize awarded to “an outstanding work of contemporary New Zealand art”, while Aotearoa Contemporary is being unveiled for the first time, setting out to “provide a showcase for what is new and current in Aotearoa diverse cultural environment”.

However, there was palpable synergy between the two events - opening on the same night - and profiling a culturally diverse display of the hottest and slickest of New Zealand’s contemporary artists. The vibe of both was overwhelmingly fresh, edgy and new, perhaps more so this year than The Walters Prize has historically felt.

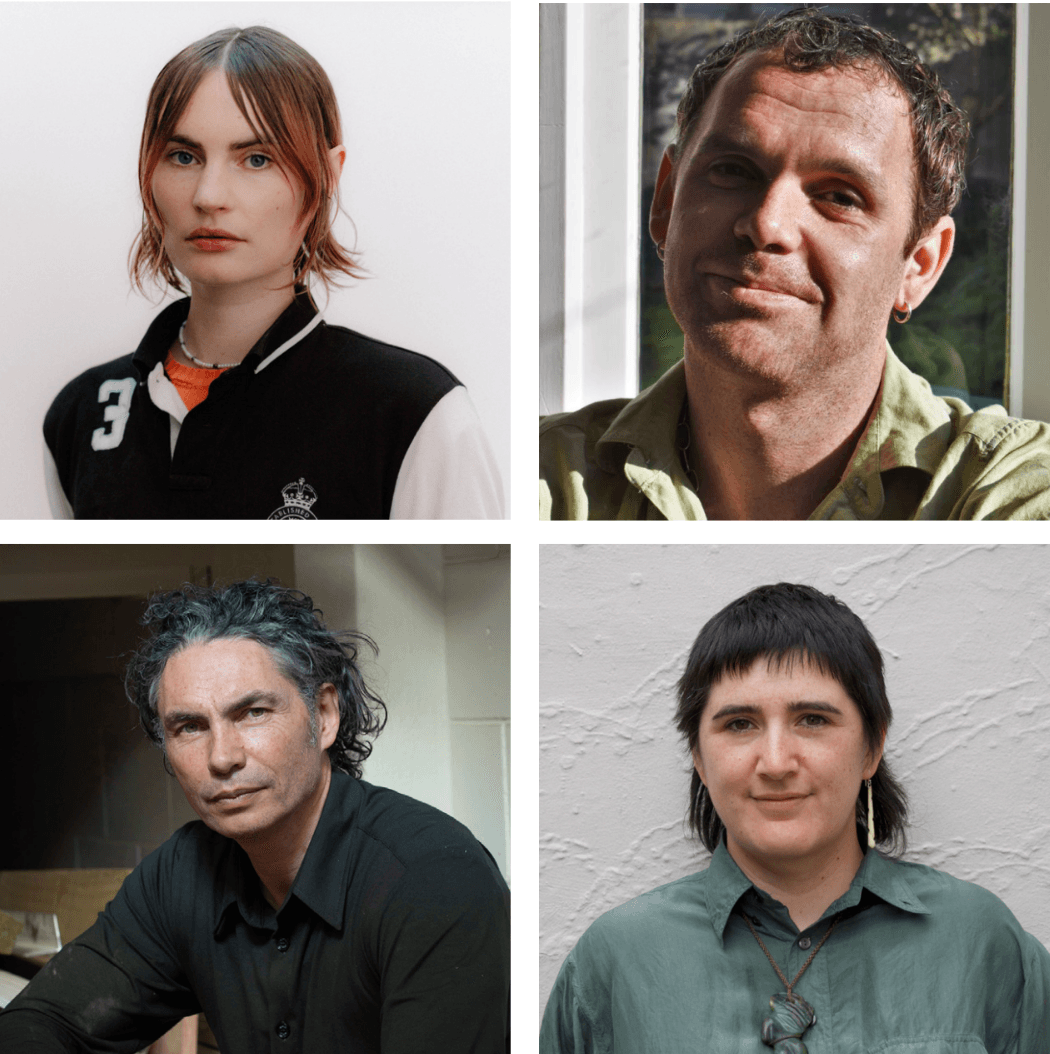

The Walters Prize finalists this year, Juliet Carpenter, Owen Connors, Brett Graham (Ngāti Korokī Kahukura) and Ana Iti (Te Rarawa) revealed their their solo presentations at the opening night (5 July), together with the new triennial, featuring 22 artists and collectives from New Zealand.

“This year, you’ll note that three of the four nominations for The Walters Prize are emerging or ‘young’ artists," curator for The Walters Prize and acting curator of Pacific Art, Cameron Ah Loo-Matamua, tells The Big Idea.

This is significant for a prize promoted as “New Zealand art’s most prestigious”, demonstrating that New Zealand contemporary art is having a moment - it’s “hot right now”, especially among the next generation.

Inclusion and diversity are perhaps nothing new for The Walters Prize - it has a long history of platforming diversity in practice and exceptional New Zealand art for national and international audiences.

A stand-out example is the last Walters Prize winners, Mataaho Collective (who won it with the remarkable Maureen Lander). The impressive collaboration between four Māori women artists went on to win the prestigious Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale 2024 for Best Participant in the International Exhibition. The prize has an international reputation for recognising innovative, diverse contemporary art.

This year however, there is an overwhelming feeling of freshness to works, perhaps more even than in years prior, the vibrantly busy launch at Toi o Tāmaki, with live musicians including LEAO and DJ BBYFACEKILLA and dance performances set the stage for a big interdisciplinary moment in New Zealand art history.

So what of the artworks nominated this year? What is the diversity of media and practice?

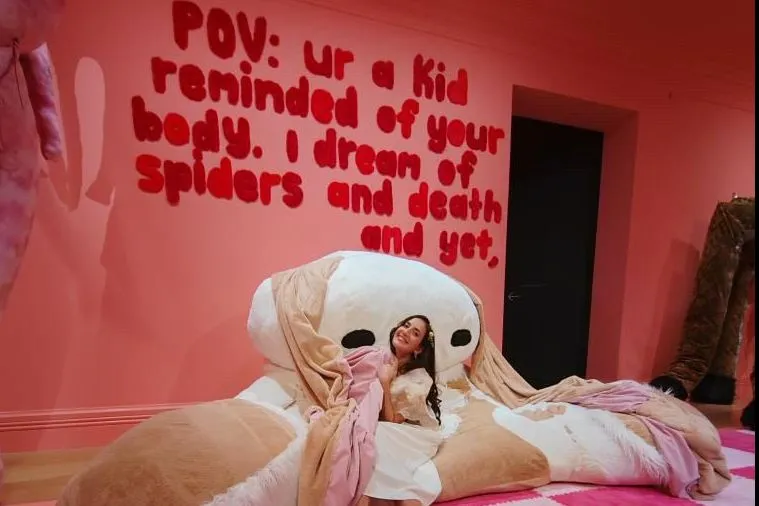

They include immersive video art in a car (EGOLANE by Juliet Carpenter); narrative architecture telling of historical Iwi-coloniser relationships (Tai Moana Tai Tangata by Arts Laureate Brett Graham); disturbed egg tempura paintings (Incubation by Owen Connors) and video and sculptural installations (The woman whose back was a whetstone by Ana Iti).

Against all odds (many of these exhibitions were originally affected by the pressures of the global pandemic), they are striking, impressively executed, and unique.

Curator Natasha Conland delivered a beautifully composed acknowledgement at the start of the launch night in Te Reo, before smiling widely and announcing “There will be no more speeches tonight - only art and a party.”

It was the biggest and baddest art event I've attended in Aotearoa since the pandemic - and one to be widely appreciated over the coming months while the works are on display in the gallery.

This year's Walters Prize, boosted by the novelty and intrigue of the Aotearoa Contemporary Triennial, seems to be the perfect platform for contemporary visual art, sometimes seen as rarefied and less accessible to a wide public. Ah Loo-Matamua supports this idea by saying The Walters Prize has been reframed this year by virtue of the coupling with Aotearoa Contemporary.

“Through the curatorium, we want to expand the reach of the gallery into different spaces, to challenge the criticism that we sometimes get… to enhance new work for the gallery, prioritising the new and emerging.”

This includes a larger contingent than before of Indigenous artists, Ah Loo-Matamua outlines, “working out of non-traditional and community arts spaces, such as the marae to create work…added to that, artists of diverse gender,age and cultural backgrounds, such as The Killing, who work with voguing and ballroom, youthful performance cultures, are highly represented in Aotearoa Contemporary, just adjacent to The Walters.”

This bolsters New Zealand Aotearoa’s reputation as a progressive and inclusive space for the arts, on a world stage.

There is a “powerful, playful and joyous feel”, to this year’s The Walters Prize, Conland adds, due to many contributory factors - the sea change that the pandemic precipitated on the collective psyche, the urge for new, engaging and relevant art as a respite to critically tense geopolitical situations and the desire to bring art in Aotearoa to the fore.

Having Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei as a Principal Partner also means that they are a “host and platform for these young artists”, and so the exhibitions “support their vision of Auckland Tāmaki Makaurau as a multicultural centre for the arts in new and exciting ways,” Conland details.

Conland, who has been a curator for The Walters since 2008, describes this year’s entries as "innovative" but highlights the objective of the award, to “point audiences towards artworks, rather than a career”.

She adds “The Walters Prize looks for memorable moments in the New Zealand arts landscape, it really marks our influence and puts us on the map,” she adds. “Unlike, say, The Turner Prize in the UK, we’re not necessarily looking at the award as success in the lifetime of an artist, but a work or exhibition that has changed and shaped the course of art history in New Zealand, irrevocably, and therefore the international art scene.”

The Walters Prize finalists are nominated by an independent jury for artworks exhibited in the preceding two years that have made an outstanding contribution to contemporary art in New Zealand.

To determine The Walters Prize winner from the four finalists, an international judge (this year it is Professor Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung) is invited to New Zealand to view the artworks presented and assess their merits.

The winner of The Walters Prize 2024 will be announced at a hotly anticipated ceremony on 4 October in Tāmaki Makaurau.