Reflections on Toi Te Kupu - Day Two

Leading Māori choreographer and performing artist Jack Gray attended the two day Toi Māori Wānaga Toi Te Kupu: Whakaahuatanga in Auckland - he covered day one (read here) and now wraps up day two.

I showed up for my second helping of Toi Te Kupu: Whakaahuatanga at Te Pokapū, Aotea Centre, for morning tea; the social vibe was more relaxed, and hongi and jokes showed that people had passed through the first day's formalities.

It seemed like fewer people were there, but that is always the case with opening days where people show up to represent versus the following ones (attendance was approximately 250 people).

I found it interesting how subtle everyone was; there were no major bold networking moves, just more pooled connections. Even people interrupted in a non-aggressive way. I had a friend whom I tried to connect with on several occasions though our time together was not meant to be, save for me quickly agreeing to be part of their next kaupapa, as is typical with the Māori arts community.

Te Ranga Tuarua - Day two

He kōrero-ā-paewhiri: Ngā Rautaki Mahitoi-ā-Iwi | Panel Discussion: Iwi Arts Strategies

This powerhouse group carried the heavy hitters - affectionately known throughout the conference as "The paepae," amongst other Māori influencers on the front lines.

Joe Pihema (Ngāti Whātua o Ōrākei) is striking in his ahuatanga, a commanding rangitiratanga with experience in lectureship and journalism presenting.

His potent reo speaks to 400 years of migration, wars, and conquest in Tāmaki Makaurau, which saw hapu and iwi such as Ngaoho, Ngati Huarere, Ngati Awa, Ngaiwi, and Ngariki come and be displaced.

Eventually, he says, a tribal group known as Waiohua settled around the early 1600s. Cut to 1840, and there is change overnight after the Treaty is signed. Ngati Whatua of Orakei agreed to hand over approximately 3000 acres to establish a township. Hobson's decision to move the capital from Kororareka to Auckland in 1841 was a severe blow to Ngāpuhi. The looting and subsequent burning of Kororāreka by Māori shook the settler population.

Joe Pihema. Photo: Jack Gray.

Pihema then acknowledged the recent passing of Joe Hawke, one of the leaders of the 1977 Bastion Point protest. He had assisted Dame Whina Cooper as secretary of the Matakite organisation during the 1975 land march and played a leading role in the occupation of Bastion Point from 1977 to 1978.

"This was about iwi trying to gather strength at the right time, to answer the challenges at the door."

Moving forward, Pihema discusses a recent "art strategy born out of a cup of tea" with Rangimarie Hunia (Chief Executive of Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei Maia) and Te Kurataiaho Kapea. Who thought, "wouldn't it be lovely if we were able to adorn marae in Ngāti Whātua?" Kākahuria te Whare is a "collective driver for our people," showing that "if you live in Auckland, it's a very dynamic world."

He shared how an ancient pa site became a pony club that was gifted back to the people to form a nursery development at Pourewa, completed in June 2020.

Reimagining Ngati Whātua presence through Pou: "Ka rewa te kōrero, Ka rewa te pou" - he urges Māori to elevate the narrative and to tether it to the connections above and below the ground in our hearts.

At this point, it is clear that the issues between western time and whaikōrero are beginning to jar, and looking at the thin time frame, each speaker cannot be as prolific if we want to get to the other side in time for lunch.

However, context is everything, and these kaikōrero are rich and abundant, generous and openhearted. Mihingarangi Forbes, the dazzling MC, is running back and forth, no doubt relaying time checks and tightening and loosening the grip as needed.

The disruption continued with issues with the photo clicker, showing the technical challenges for some of the speakers. I elbow my friend as we clock all the interactions and tikanga at play.

Kura Te Waru Rewiri (Ngāti Kahu, Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kauwhata, Ngāti Rangi) was born in Kaeo, Whangaroa, encouraged to study art by a teacher and early mentor, Buck Nin.

She left the Far North and attended Ilam School of Fine Arts in Ōtautahi/Christchurch from 1971 to 72. She talks about her journey going back to the people. In 1985, after a 9-year teaching career, she returned to painting full-time and reflected her ideas in an exhibition called Ahau: this is me.

Kura Te Waru Rewiri. Photo: David St George. Courtesy Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

The impact of Christianity led to the Māori prophetic movement; the Ratana faith came from Tahupotiki Wiremu Ratana, who led the masses on his divine vision aiming for compromise between both spiritual world views.

She also discussed the Treaty - particularly the 'X' symbol - questioning the Pakeha perception that by signing, Māori were giving away their sovereignty.

She then shows us modern images of koro and koroua up North wearing special blankets, signifying they did not cede their sovereignty. Kura became a senior tutor in Maunga Kura Toi a Bachelor of Māori Art at Northtec Tai Tokerau Wānanga. It led to her focus on questions of how our buildings are inclusive of our people: "How we occupy space and coexist together."

At this point, we had only "ten minutes" for the final speaker - which again created a rupture in the space, highlighting the very curated Western structure of the wānanga.

Moana Tipa (Kāti Mamoe, Kāi Tahu, Ngāti Kahungunu, Celt) walked to the podium, her sharp bob and presence taking us all in. She cuts to the chase and immediately draws us in.

Saying it was her mother's love of the Māori language, music, drama, and the arts that influenced her, "the tiny remnants of Te Reo were everything we had. To keep something alive because of the scarcity where I was living".

In 1997, she started working for Ngāi Tahu Development Corporation, co-ordinating contemporary visual arts culture amongst Ngāi Tahu artists from the time of Settlement with the Crown in 1997.

"There was already a taumata of experienced practitioners, generations of artists already developed, and voices in lockdown for 135 years".

She affirms they knew their aesthetics instinctively and did a lot themselves creating a series of exhibitions. "We didn't explore Ngāi Tahutanga" she says, "Ruia taitea kia tu ko taikaka anake: Strip away the sapwood and leave only the heart."

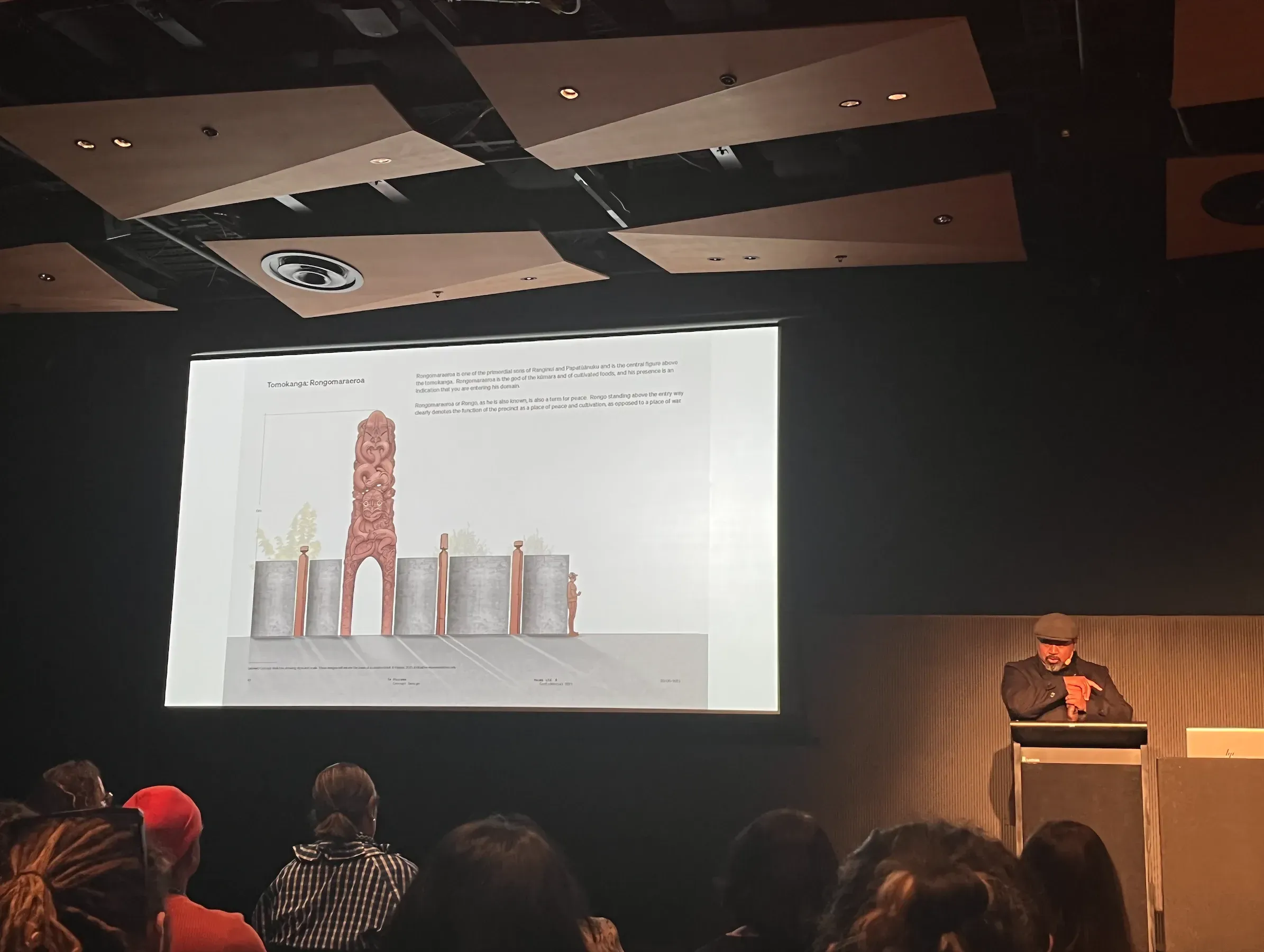

He kōrero: Kia kitea Te Mana Motuhake i te taone | Talk: Visual Sovereignty in the City

Bernard Makoare. Photo: David St George. Courtesy Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

Bernard Makoare (Te Uri o Hau; Ngāti Whatua Te Waiariki, Te Kai Tutae; Te Rarawa Ngāpuhi-nui-tonu) also clocks the time frame - and gets stuck in.

He says that histories explained through whaikorero address ancestral obligations to all the affiliated marae across the country. A renowned carver, he acknowledges whakairo as a place for imagining mareikura and whatukura, then speaks to other influential artists, including Dr. Sandy Adsett's six decades of painting Māori symbology.

Finally, he mentions Jim Viviaere, artist and curator, and Teresia Teiawa, scholar, poet, activist, and mentor who "woke me up" to the "bigger story of Oceania."

Photo: David St George. Courtesy Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

It is lunchtime, and I have a great chat with an artist/activist who says the talks are so institutionalised, and they are down for some more critical self-reflection.

Well, it's the commentary after rather than the talks themselves making sense. I thought about some of the playful encounters and panels, and we agreed to connect up some time to discuss this further.

He kōrero-ā-paewhiri: Te tuhi i ngā tāhuhu kōrero mahi toi Māori | Panel Discussion: Writing Māori Art Histories

Chair Karl Chitham (Ngā Puhi) focuses the spotlight firmly on the speakers who now know the drill.

First up is Deidre Brown (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kahu), a New Zealand art historian and architectural lecturer. I feel like I have seen or spoken to her before, and I rack my brains.

She is the first Māori professor of architecture in the world. We hear about advanced abstract sculptural formalism and a body of work in the forms of drawings, photos, prints, and paintings.

Next, we discuss constructivism, minimalism, and responsiveness to the times. War profoundly impacted whānau; peoples Dads and Uncles were killed in World War II, leaving six decades of intercultural and intergenerational conflict.

We reflect on critical considerations, conservation, the latitude of interpretation, and access to work in archives. Finally, there are comments about support structures, ongoing visibility, access, and being "cared for by an institution."

Also speaking is Reuben Friend (Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Pākehā), whom I haven't yet actually met but enjoy his space-disrupting swag.

Art histories in the conversation come up, e.g. why wasn't this artist in Toi Tū Toi Ora? And that discourse asks hard questions like, "How many Māori artists have had an exhibition at the Auckland Art Gallery?"

The example of Fred Graham, Sandy Adsett, and Robyn Kahukiwa are artists crucial to our histories, and it is essential to write them now "because they won't get recorded otherwise."

Finally, Taarati Taiaroa (Te Āti Awa, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Apa, Ngāti Kotimana), whom I had met before (and played a ball game with), is subtle, intelligent, and quietly spoken.

North Island-centric art elitism shows gaps for the next generation. "can Māori histories affect change and make a difference?". As a collective, these roles and influences leave us to ask: "Who is making art for whom?"

He kōrero-ā-paewhiri: Ngā Kaupapa Ringatoi | Panel Discussion: Artist Initiatives

Deputy Director of Objectspace, Zoe Black (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Hine, Ngāti Pākehā) is a beautiful speaker and calmly chairs the space for this final group of panellists.

At this point, this intentional listening and absorbing are near the marathon's last bend, my kite is complete, but I do my best to give my courteous attention.

Chris Bryant-Toi (Ngāti Ruawaipū, Ngāti Porou) introduces himself as an aging rangatahi, eliciting the audience's laugh.

He describes Te Ātinga, a Contemporary Māori Visual Arts committee that focuses on supporting Māori artists to explore, experiment, develop and share their creative interests, whom he has been with since 1993.

Chris Bryant-Toi. Photo: Jack Gray.

The discussion is about space to rethink and reposition. To question 'how do we start again?' and 'what can we do to mark a time?' From inviting a network of Indigenous artists to climb Tarawera, asking 'how do we lead and conduct ourselves?'. A story about a tohu, of Dame Te Atairangikaahu being acknowledged by Wetini Mitai-Ngatai at the summit when right on cue, a kahu flew by and activated the mauri.

Simon Kaan (Kāi Tahu, Kāti Irakehu, Kāti Mako ki Wairewa) expresses aspirations to take tupuna work worldwide. Paemanu: Ngāi Tahu Contemporary Visual Arts was formed by a group of established Ngāi Tahu contemporary visual art professionals, dedicated to advancing Ngāi Tahu visual culture through creative and innovative artistic expression.

Discussed are the role of government agencies such as Te Waka Toi, Creative New Zealand, and entities outside such as Toi Māori Aotearoa. What is the part of reinterpreting the mana of our people, how our tipuna made their marks, and how we connect back?

Lastly, Matariki Williams (Ngāi Tūhoe, Ngāti Hauiti, Taranaki, Ngāti Whakaue) shares ideas around ATE Journal of Māori Art, an annual, peer-reviewed journal with an explicit focus on Māori art, artists, and art movements. Curators as burgeoning editors and exploring the assumption you need to write from a certain point of view.

He kōrero-ā-paewhiri: He kōrero whakakapi | Panel Discussion: Round-up

Nova Paul (Te Uriroroi, Te Parawhau, Te Māhurehure ki Whatitiri, Ngāpuhi) and Shannon Te Ao (Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Wairangi, Te Pāpaka o Maui) speedily take us to the final countdown, with their absorbing, witty and reflective in and out-of-body experiences of being at the wānanga.

I understand the rabbit-hole-ness of the event and all the swirling energies that came with each speaker. Eventually, Mihingarangi signs out and hands it over to Te Arepa. I think we all sing a waiata - was it Whakaaria mai? I must have been on robot Māori mode at that point.

I run around and make sure I say goodbye to a couple of people, who ask me for my thoughts, and without really having processed and speaking instinctively, I say it was great.

And yet, while this was a showcase of high-profile and recognised Toi Māori artists (and supported within institutions), I feel many grassroots artists whose work in the community is under the radar, funded in different ways, were left off the panel list (or the guest list even).

The standard ticket price reflects that it is a fully catered event, across two full days and includes a networking event on one of the evenings, as well as the range of speakers hosted from across the country.

Whether there are ways to make it equitable or that some sessions are free for Māori artists is something worth considering.

I also thought about how strange it was that after a pandemic, there was no focus on digital arts to connect communities in different ways socially. So as I walk and talk with a stranger, I give her a rundown on the mana of contemporary dance and how performance brings energy to the space. Across the road at the Queen Street bus stop, bright, vivid posters of Atamira Dance Company's upcoming show Kaha pop out like futuristic whatukura and mareikura. I showed her our Instagram, and she followed us. I think about the cyber following and how much more complex our tribes are becoming.

I bump into a gaggle of friends heading to a bar for post-wānanga debriefs. I try to wiggle away but then get swept up in a tide of obligation. It would be rude not to whakanoa, so I briefly joined the mass for a drink. The rest, as they say, is history. Cheers!

Jack Gray, Elisapeta Heta, Ngahuia Harrison, Zoe Black. Photo: Jack Gray.