Road to ruin

Written by

Curator and writer Andrew Clifford talks to artist Brydee Rood about life in transit, in this interview courtesy of arts publication White Fungus.

* * *

After growing up and studying in Auckland, New Zealand, Brydee Rood has spent much of the last few years working abroad, including residencies at Van Gogh Huis in Zundert, Netherlands, the Sowing Seeds International Artist in Residence Camp at Gelawas Village in Rajasthan, India, and Headlands Center for the Arts in San Francisco as the Fulbright-Wallace Arts Trust Award winner, as well as stints in Australia, Germany, Japan and Mexico. Preferring to work in community settings outside the white cube, her work has been shown in urban back-street alleys, city canals, and on the side of working rubbish trucks. This migrant approach is aided by a DIY approach to ad-hoc structures made from found materials as a way to think through issues of consumer culture, waste and sustainability.

In February this year, Rood presented the exhibition Passageways at the Pah Homestead Wallace Arts Centre, featuring five video works from her recent travels, including striking footage of a Don Quixote-like horseback pilgrimage, a surreal Rajasthani twilight parade, and the pendulum swing of an abandoned tape measure in a rubbish dump. Auckland writer Andrew Clifford caught up with her after the opening to ask about life in transit.

Andrew Clifford: Having spent a lot of time on residencies over the last few years, do you think there’s something about a residency situation that benefits your work, or lends itself to working differently to what you would do at home, aside from the obvious advantages of time-out from routine commitments, and new environments for inspiration?

Brydee Rood: Maybe it’s the chance to absorb and reflect upon direct experiences within different cultures. I am fascinated with human beings and how we move through the land we inhabit. Different places host a diverse range of subtleties and I’m curious about, and sensitive to, these variations in life. I want to experience diversity and changing environments because my experience of these things translates into my practice; it’s a learning experience about finding knowledge. I also feel a certain freedom when I am away from home – sometimes at home I feel weighed down, like I’m treading water in a murky eel pond, splashing about in daily sludge, trying to stay afloat. I'm sure these feelings are merely perception but, well, perception frames our thinking...

Artist Shigeyuki Kihara recently remarked on the local impact of residencies. In terms of the sense of exchange that comes out of working with a local community, how hard is it to shift from talking to them rather than with them, or working with a situation rather than using a situation? When you return home with all your new work, photos, ideas and inspirations, what does the residency leave behind? Is it possible to also be a benign presence with zero impact, in either a social or environmental sense?

No matter where I am working, I try to keep these thoughts in mind – and of course it’s a vast grey area because some traces are positive – the power of new thoughts, of being involved in new processes, the pleasure from experiencing or participating in the creative journey and sharing an artwork with a community. These are all traces of a project which I am happy and honoured to leave behind.

When I was working with Kasanova (a charming chestnut steed) and his owner/rider Tessa at the Presidio Riding Club at Headlands, I was apprehensive and worried about how Kasanova was feeling during the live installation. It was very experimental for me and I had no previous experience with horses except perhaps riding the occasional pony as young girl. I trusted my instinct and maintained continuous eye contact – speaking to and (I felt) connecting with Kasanova at every step of the installation. But it wasn't until the end of the day when we were finishing that I received a gift from Kasanova – a huge horsey kiss, affectionate head-butt and toothy grin, and in this moment I knew our exchange had been positive. I felt confident that Kasanova had enjoyed his collaboration with me and it was a very happy moment for me also.

If I take this example and shift it to Gelawas village in rural Rajasthan, India during the Sowing Seeds International Artist Residency Camp in 2011/12, I would say that I could also measure the social success of my project by the levels of excitement, laughter and bright, cheerful smiles of those who shared and participated in my projects. And in an environmental sense we made a real effort to reduce the levels of plastic waste in the village and to transmit these actions and sentiments of positive energy, care and connection to the land. I had the pleasure of meeting the Gelawas Village Chief one year later and he extended me a warm greeting, a happy meeting followed by a genuine invitation to return.

I’m interested in the increasingly performative nature of your practice and how the presentation of work is becoming more temporal. Although sculptural in the sense that it often explores materials, outcomes are usually delivered under the auspices of a performance. In particular, in most of the residency works shown at Pah Homestead, the work is delivered as a kind of parade that involves make-shift constructions, members of the community, and the artist is visibly present too. So I’m curious about what the parade as a specific form means to you, or if it would be more appropriate to think of it as a march or protest?

I think it slips around between parade, march, protest, pilgrimage and procession, and is often celebratory by nature – the rubbish bag being inherently balloon like, lifting and rising. And also ritual pilgrimage/procession-like as I seek new modes of knowledge and spiritual connections, exploring existing relationships between humans, waste and habitat by testing out interactions between these ideas in different environments and contexts. Especially in the work with Kasanova, it felt in some ways (for me as I trailed it unsteadily with a camera) that it was a navigation of material and site, with weird historical overtones in the act of tracing and retracing steps up a sacred hillside.

There is certainly an element of protest too. In some ways it’s a defiant action that I’m employing these typically discarded materials – elevating them in our visions, exposing their sculptural form and waving them about, invoking a communal action and direct engagement. I guess I’m seeking visual answers to a complexity in life that I can't easily explain. In each parade, whether it’s through a village street or remote landscape, I'm looking at how the various conceptual and formal aspects of the work are mobilized, and the parade becomes an unpredictable choreography, open to engagement and responding precariously to the environment.

Is a parade/march/protest helpful as a form because it is a kind of performance that doesn’t need to be understood as art?

I'm driven by intuition, sensitivity and a lively curiosity for the world we inhabit. I’m motivated to explore diverse and more sentient forms of expression in my practice - to experiment with an active palette and strive for creative vehicles, which resonate through time and space. A parade/march/protest as a sequence of fluid actions is a more transient and active visual dialogue so it feels apt to employ and further explore these methodologies in my art making. Often the more traditional art forms leave me feeling a bit stuck and dissatisfied. I love to challenge myself and, as a consequence, challenge perceptions. These are captivating times; failing (or not failing) capitalist economies, extreme weather patterns, dwindling "resources", vanishing species, sinking islands, and yet human beings seem mostly static, following existing habits, living in current structures. I really struggle to make any sense of, or find any peace with, the innumerable contradictions and conflicts of daily life, and the direction of my practice slides around within this wider social-political-environmental context.

Thinking of a parade/march/protest as a kind of community presentation for a community audience, the Headlands work with Kasanova is quite different because it’s more of a lone activity, which seems to be presented for the camera rather than a live audience?

In Exercises With Kasanova there was an immediate connection with the wilderness. For me this was part and parcel of my residency experience – Headlands Center for the Arts sits cradled within the Golden Gate Recreational Park. I would wake up in the morning to turkeys warbling outside my window, at night often sharing the somewhat jittery walk from studio to home with fellow artists – across the damp field, ever so slightly wary of the shining deer eyes catching in the moonlight or the swift paws of a Coyote passing in the shadows. It didn't take long for me to notice the horse stables, track down some riders, agree to attend a stable meeting, introduce myself to local horse people (get laughed at) and receive a heartwarming offer of participation from Tessa and Kasanova.

There may not have been an obvious human presence in this work, but everything that was there was present, from 'Bear' the little dog who follows us, to the wild grasses underfoot, sky above, warming sun, blustering wind, and the sheriff who'd seen us from afar and drove along to interrupt our footsteps and ask many general horse-related questions before waving us along to continue. It was all part of the live installation experience, clarifying for me that I work with what is there. It was a rare gift to work in this environment.

I view this piece as a series of exercises, which I followed from my position behind the lens. The lone wandering echoed my practice at Headlands, of taking many walks into the surrounding hills and connecting with the land. I hope to find more opportunities to explore different environmental connections in my practice, as well as working more communally because both offer valid insights that contribute to my wider visual research series: The Waste Whisperer.

Motion and kinetics are also recurring motifs of a performative nature – there is the video of the pendulum, and your more conventional installations often have materials that move in some way, usually aided by the lightness of the materials. How do light, translucence and movement fit into your world view?

Movement towards lightness and change is integral to my work. The video work Rubbish Pendulum is a quiet meditation on waste with a veil of translucent rubbish bag material hovering shroud-like over the screen, but also cut open; open to new ideas and knowledge. It comes back to the spiritual narrative behind many of my projects, which is perhaps a gentle optimism and an uncompromising shift towards sentient feeling and hope - perpetually seeking new perspectives, reflecting light, responsive to wind, water and intervention. In my process there is a material navigation going on, of plastic and waste in a rapidly changing environment, connected to the body, to touch, movement, breath and ways of being and finding balance.

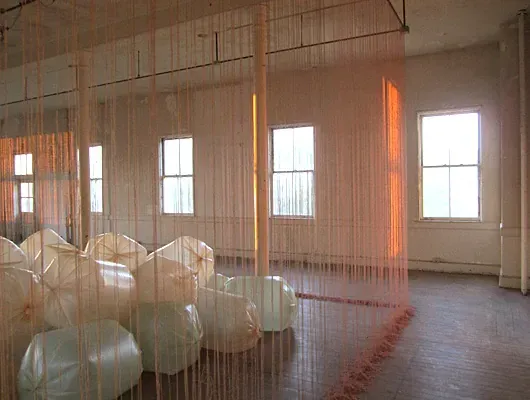

To be with you, to be free, my installation for the Spring Open House Exhibition on April 22, 2012, began with 8 spools of discarded yarn, scavenged from the studio building. This yarn was then drizzled in 6,400 lengths and attached with 800 pieces of tape over 3 weeks and 1 day, drawing an ephemeral outline of a space – a translucent space to embrace an idea, spun and caught in the air. Everyday light channeled along the walls of string, setting ablaze the dusty old yarn and making it flare gold for the duration of each sunset. To end this installation, I opened all the windows, inviting the wild Headlands wind to blow through and redistribute the fragile installation. It has something to do with the precarious nature of ideas balanced within a delicate structure. It's like saying; here I behold a thought, just for a short time, to articulate something precarious and unknown. It was air that filled the inflated rubbish bag balloons and air that buffeted and billowed the installation to its end. Perhaps it also speaks to the nature of human relationships, our materiality and our habitat?

- Article courtesy of White Fungus