Soapbox - Doing arts ain’t for sissies!

Written by

Here’s Playmarket director Murray Lynch on the history, decimation, and what should happen next.

It’s a tough life trying to make a career in the theatre. This will not be news to any practitioners but we need to improve the situation. Too many professionals are surviving on too little income.

In my fifties I took some time out from being a theatre manager and director to study. I had been in the profession since 1973 and most recently had run a theatre company for six years and felt it was time to be free of responsibility for others and to feed my mind. After that study was complete and I graduated from an institution for the first time in my life, I set out to work as a contract director only to be confronted with the industry in worse shape than when I had begun.

I had entered the profession into a company of permanent actors and backstage staff, like the model most of the subsidised theatres sustained in New Zealand for at least twenty years. This was an excellent way to develop skills and direct, design, act, build, clean toilets and the other necessary roles that keep a theatre open for business. I learned so much through the process of staging a new production every four weeks.

I was paid $150 per week, the equivalent of $1,100 today.

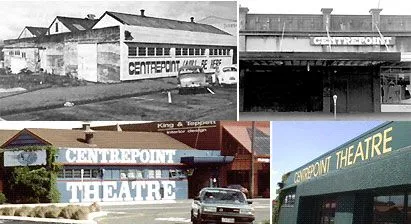

As a young man I had the opportunity to work every month with experienced and skilled performers. I even had extraordinary opportunities to direct – including Waiting for Godot (I was also responsible for designing set and lighting and playing Lucky). Before very long I was head of Centrepoint Theatre in Palmerston North, with fully staffed workshops and permanent acting company and enough staff essential to keep a theatre running. I was paid $150 per week, the equivalent of $1,100 today.

In a responsive rather than designed career, I found myself in management roles sitting on the employer’s side of the table at union negotiations, whilst also being a huge supporter of Actors’ Equity and Backstage Workers’ unions. The strikes in the 80s at the theatre I was in charge of were a challenge. In those days presentation of union membership cards was necessary before commencing rehearsals. Everyone knew what minimum to expect in their manila envelope pay packets and overtime and other allowances applied. I have often been responsible for setting fees of course, but squeezing more money from the limited annual budget is easier to justify to a board when minimum rates are set.

I am saddened that today some actors and backstage workers are paid less than the living wage.

After the Employment Contracts Act in 1991 - which made union membership voluntary - the erosion set in. No longer would it be compulsory for the hard-won conditions to be adhered to, and fees would fall behind a level that allows for a sustainable career. Not long after that company structures were abandoned and ongoing work situations became a thing of the past. Of course, many sectors of the national work force are suffering too, but with the low level of payment for most arts practitioners and the instability of work opportunities, arts employment has reached untenable levels.

Of course, many sectors of the national work force are suffering too, but with the low level of payment for most arts practitioners and the instability of work opportunities, arts employment has reached untenable levels.

It is a no brainer that the ability for management to pay is aided by compulsory minimum standards.

In 2008, the year which followed my master’s degree, I was not expecting to earn huge sums but I was hoping the six productions I directed over 35 weeks of the year, each of which required weeks of preparation, would fetch more than the $28,000 I received for my efforts. About $500 a week for a full years’ work after four decades of practice.

I am saddened that today some actors and backstage workers are paid less than the living wage, and that’s when they are fortunate enough to be working, which is sporadic. This profession involves hard work and long hours. It is time all theatre practitioners, who are now more qualified than was possible when I began, earned at least a living wage. And fees at the upper end require re-assessment too.

Profit-share is a wonderful empowerment for practitioners but - too often - yields zero income results.

Not only have fees fallen behind, so have the opportunities to earn in the theatre. There are fewer subsidised theatres. Profit-share is a wonderful empowerment for practitioners but - too often - yields zero income results. I acknowledge that many profit-share productions exist for the betterment of careers, development and simply a chance to work, but somehow that development and exposure needs to be supported.

There are ways we can grow the support but the truth is that theatre is no place for sissies*. We must lobby theatres to adopt a living wage policy. Follow the example of Barbarian Productions, the first theatre company to be accredited with Living Wage NZ. The current coalition government is working on reintroducing a renewed PACE (Pathways to Arts and Cultural Employment) scheme which gives practitioners some confidence that their choice of profession is valued. It is also time for other sectors such as television and film - which benefit from the training, skill and experience the theatre develops - to contribute more financially.

*Sissy as well as the derogatory effeminate also means feeble or cowardly.

Written by Murray Lynch

Murray is currently Director of Playmarket, representing playwrights. Submissions for Playmarket’s Adam NZ Play Award are welcome until 1 December