Stanza & Applaud - Passing The Torch To New NZ Poet Laureate

National Poetry Day has been ushered in with the announcement of the country's Poet Laureate - the departing Chris Tse interviews his successor Robert Sullivan (and vice versa).

Phantom Billstickers National Poetry Day (22 August) has arrived, with activations all across the motu to celebrate all things prose.

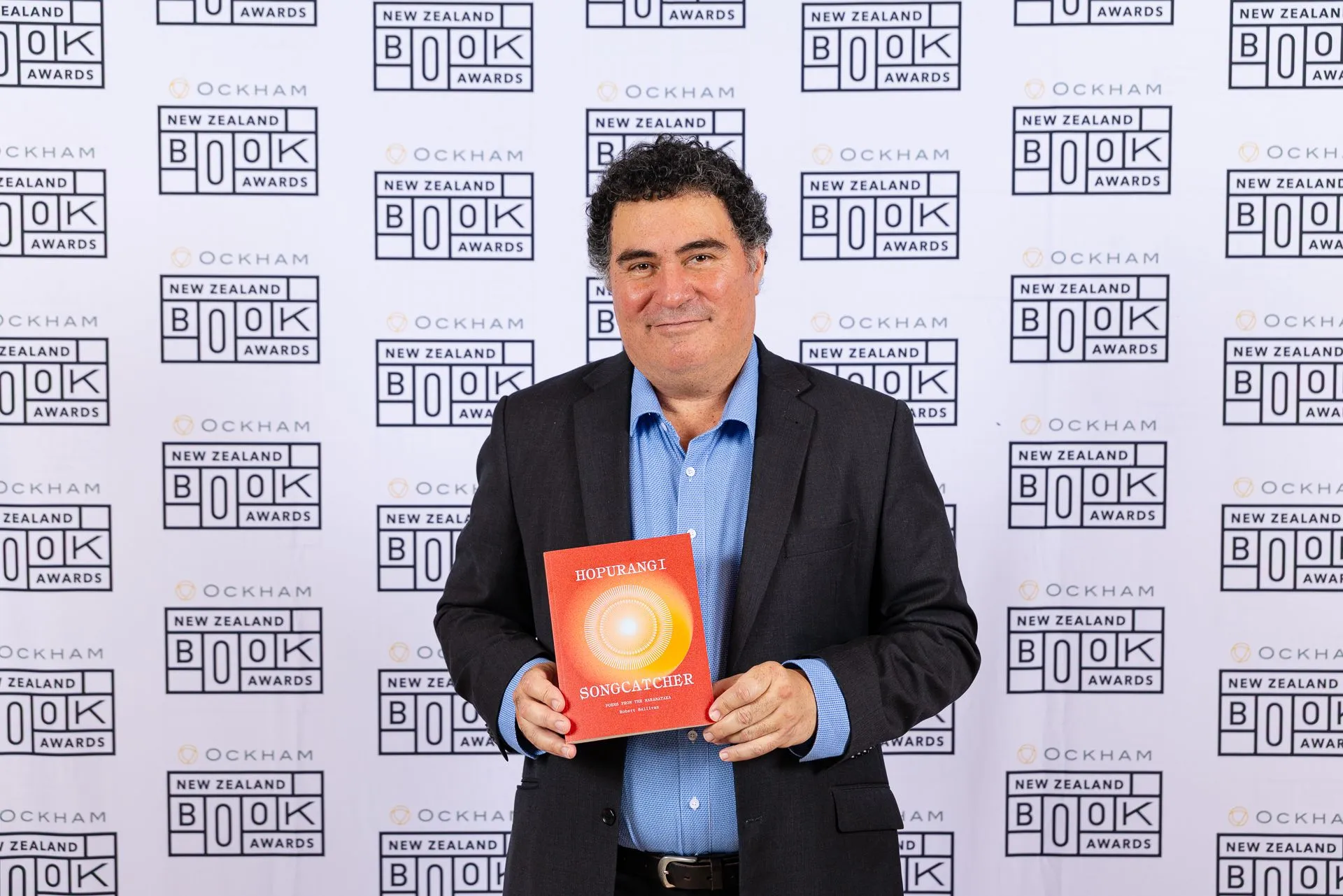

One of the biggest moments of this year's festivities - the announcement that Robert Sullivan has been appointed as the New Zealand Poet Laureate for 2025–2028.

The baton is passed from Chris Tse, who was given an extended five year run with the role after being bestowed with the honour in 2022.

In his last act as outgoing Poet Laureate, Tse welcomed Sullivan into his new position - and discussed their love of poetry.

Chris Tse: Kia ora Robert! Congratulations on being named New Zealand’s next Poet Laureate. Where were you when you got the news and how did you react?

Robert Sullivan: Kia ora Chris! I was at home cooking dinner. Kind of astonished but also felt like it was a time to be tau, just to remember our tupuna and whānau, and then to remember friends from poetry who’ve all sung their hearts out and kept singing their poems into the sky.

CT: Let’s go back to the start of your poetry journey. What’s your earliest poetry memory?

RS: I was in Year 6 in Primary School and our teacher at Onehunga Primary - Mrs Nair - got the class to lie down on the school field and write about clouds. The other kids wrote about fluffy bunnies, and candyfloss. I wrote about the floating alligator I saw. Mrs Nair got us to write our poems in cloud shapes which we filled with cotton wool and she hung them from the classroom ceiling. She was an amazing teacher who talked a lot about going to university too.

CT: I’ve heard from so many people over the past few years that it was their teachers who set them on a lifetime love of literature and poetry - particularly if they introduced their students to books or authors that weren’t the typical set texts.

RS: What’s your earliest memory of poetry, Chris?

CT: Probably sitting on the mat at primary school and reading poems along with my class and teacher. I started writing poetry as a teenager because my friends were doing it, but it quickly became something I couldn’t stop doing, particularly once I got to university and began immersing myself in poetry and literature. I’m forever grateful to have had some excellent and encouraging teachers and mentors during this period of my life, some of whom introduced me to your work! Your poetry is noted for how it explores and incorporates te ao Māori and te reo Māori. In ‘He Toa Takitini’ from Tūnui | Comet you write about the tension of writing in both English and te reo Māori for different audiences, which you call “an interesting problem”. Is this something you might explore further during your term?

RS: Yes - I’ll always go there! My te reo Māori journey is a familiar one for so many second language learners. I’m currently at about intermediate level fluency–the more I learn the more I realise I need to know more. So that shows in my poetry too. When I’m more fluent, it comes out in the imagery and directness of expression. Māori language poetics is directly emotional; there’s a lot to learn about writing poetry from the words of our tūpuna, and from our te reo Māori composers of waiata, haka and moteatea. One of our tupuna wrote this amazing moteatea, “Rongo kōrero au” which in part sounds exactly like birdsong, a melodic level of sound that isn’t available to English which is quite guttural in its sound. Do you speak another language Chris? Does that influence your poetry?

CT: I grew up speaking Cantonese at home with my parents and grandparents. There’s video footage of me as a toddler speaking fluently, which is quite a shock to watch as an adult. It’s like meeting a version of yourself from a parallel timeline. I lost a lot of my fluency once I went to school but have retained enough to have simple conversations. There’s probably a correlation between my upbringing with Cantonese and why I love poetry – being able to see the world or express yourself in another language that draws on different nuances, metaphors and traditions. Like you, I’d love to be able to write a poem in my other language, but I’m many years away from that happening!

RS: That’s interesting. Hone Tuwhare spoke Māori when he was growing up, similar to you. It definitely influenced his poetry through the rhythms and personification of natural elements in his work. Have you read Chinese poetry in translation? I’ve been dipping into the Tao a little bit which feels like philosophy but I might be digressing here.

CT: When I was writing How to be Dead in a Year of Snakes, I read some classical Chinese poetry thinking that I might incorporate some forms or elements, but in the end that didn’t make it into the final version of the book. It’s something that I’m looking to resurrect for a future project I’ve started thinking about. Some of the poets in my residency cohort in Iowa City last year have introduced me to contemporary Chinese poetry, both their own work and other poets they’ve translated into English. I’ve only scratched the surface and am hoping to read more when I have a bit more time post-laureateship.

RS: I’m also thinking of your poem “Bilingual” in Super Model Minority. As well as addressing language, your poem shows the political difficulties of Hong Kong. I went to a Tiananmen Square candle light vigil in Hong Kong once - there were photographers on towers and walking through the crowd dressed in black wearing balaclavas taking photographs of people. There were 100,000 people packed into a square. It felt dissonant as the local Hong Kong police were friendly. Your poem captures it well, “...the crack/ of a thousand umbrellas calling forth their own storm…”.

CT: I’m not sure how to explain it, but watching and following the 2014 protests created this new connection with Hong Kong for me, even though I’d been back a few times before and still have family there. Maybe it’s because I was thinking more deeply about the connection between heritage and politics as part of my writing practice at the time. Speaking of writing practice, your latest collection Hopurangi—Songcatcher collects poems that you wrote and posted on social media every day, inspired by the Maramataka. It’s a wonderful example of how you incorporated poetry into your daily routine. Have you maintained this discipline since publishing the book? If not, do you think you’ll return to this way of writing?

RS: If only! I have spent a lot of time developing my fluency in te reo Māori - I’m about intermediate level - attending wānaka reo at Puketeraki marae in Karitāne to learn our Kāi Tahu dialect, which has drawn me closer to our traditions of waiata. We have wonderful composers there, such as Waiariki Parata-Taiapa, Tawini White, and Rauhina Scott-Fyfe. So, I’m re-learning how to listen and read poems. Here’s a link to a favourite song poem by Hirini Melbourne which captures the sound of the Pipiwharauroa (shining cuckoo), a bird used for navigation and to mark the warmer seasons: Pipiwharauroa. But yes, I do have plans to write another sequence, and to complete the maramataka over a longer period of time as Hopurangi only covers a few months. I seem to favour that mode in my writing - the book length sequence.

CT: I love a book-length sequence! I revisited Star Waka after you spoke at the lyric diary conference organised by Anna Jackson and Helen Rickerby. It was one of those formative texts for me and broadened my understanding of what a poetry collection could ‘do’, given that as students we are often taught poems in isolation, removed from the context of their original collections. Star Waka was the first full poetry collection I studied as a whole body of work at university and was one of the books that I thought a lot about when shaping Snakes. Why do you think you’re drawn to the book-length sequence?

RS: That’s very kind of you to say. I had some great professors at university, such as Michele Leggott, who were really into the modernist and postmodernist American poets. I read Paterson by William Carlos Williams and suddenly understood what scale could do in a poem, and also the breadth and depth of subject matter, that a poem could be a giant, the embodiment of the city of Paterson, New Jersey. Williams was also a master of the very short poem. I’ve always loved William Blake’s writing. When I was in my early twenties, I worked as a Rare Books Room assistant at Auckland Public library. I was given the very happy task of writing a bibliography on the William Blake collection of facsimile editions held there, including two original prophetic Blake publications, Europe and America. As well as length, Blake’s poetry was cosmic. This greatly helped me to tap into the spiritual nature of te ao Māori in my writing. A portal was opened.

CT: I love how poems and collections come into our lives in unexpected ways. What I’ve found interesting in the past few years is how the new generation of poets are reading or responding to some of the poets I read and studied, which has shed some new light on the work for me. I don’t think we can ever escape the cyclical nature that’s built into the arts and literature.

RS: Speaking of a new generation of poets, you are seen as representing a new wave of poets, and your laureateship reflected that. If I may say, you did a wonderful job with the laureateship. Would you like to reflect on the fantastic success of your generation to bring poetry to new audiences? I love what Tayi Tibble, Alice Te Punga Somerville, and essa may ranapiri are doing from a Māori world view.

CT: It’s so wonderful to hear students say they actually enjoy poetry and seek it out because they can see themselves in the work of poets like Tayi or Hera Lindsay Bird or Joanna Cho. I know ‘representation matters’ feels like an overused phrase these days but it’s so true. I feel so fortunate to be writing and performing at this time when there’s been this shift in the poetry scene, both in terms of who’s writing and performing, and the types of poetry events that people can go to. In Rotterdam, I went to an event that combined poetry and ballroom culture and it was so thrilling to see young poets and performers claim that space so unapologetically. Also, the audience was also not your typical festival audience either.

RS: How lovely!

CT: You’re the current president of the New Zealand Poetry Society. What sort of insights about Aotearoa’s poets and poetry have you gleaned by being in that role?

RS: It’s like a waka. You can’t have a waka without a community to build, maintain and sail it. We have so many volunteers that help the work of the society, and so much gratitude for their work and dedication to poetry. We have hopes of hosting a national poetry reading from different communities linked together online, possibly from community libraries. We host local book launches of our annual anthology at different venues around the country so we have the beginnings of that national reading–perhaps we could partner with the laureate role through our National Library to make it happen. We’ve also handed over the editor role of our magazine A Fine Line from the brilliant Gail Ingram to the equally wonderful Cadence Chung. We’re always looking to support poets to share their heart/spirit work. What do you think of that idea of having a national reading linked through community venues? Do you have any tips?

CT: I tautoko your comment about it being like a waka. This has been apparent from day one of my term as Poet Laureate and I’ve seen it in every community group or literary organisation I’ve worked with. Your idea of a national reading would be a wonderful way to bring people together and highlight the importance of libraries as community spaces. Simon Armitage has a goal to visit as many libraries as he can during his ten-year term as UK Poet Laureate, so maybe this could be your Aotearoa twist on it! It’s early days, but is there anything else that comes to mind that you hope to do during your term?

RS: Apart from the national readings and the library visits, I’d really like to open a poet laureate shop in Oamaru, somewhere in the Victorian precinct. I’d run online workshops from there, and smaller local ones. I also teach creative writing online for Massey University so that would be a good community space to work from.

CT: Wonderful! It never ceases to amaze me how hungry people are for creative writing workshops and classes.

RS: Could you share some highlights for you from being our Poet Laureate? You must have shared them with a lot of amazing people.

CT: People have been the common thread of all the moments that come to mind as highlights, from audiences and students to fellow poets. What’s amazing about this role is that it allows you to see and demonstrate how poetry can connect us all through storytelling and shared experiences. Getting the chance to perform in other countries and represent Aotearoa has obviously been amazing – I never imagined poetry would take me around the world! The one highlight I keep returning to is the inauguration weekend at Matahiwi Marae, where I received my tokotoko. It was such an overwhelming day, but also so special to be able to celebrate this moment in my life with my friends and family.

CT: How will you celebrate this momentous next step in your poetry career?

RS: Well, I’m having lunch with my mother during the day in Wellington, after teaching poetry at Massey’s Pukeahu Campus there for our campus open day, and then there’s a poetry reading Friday night in Dunedin so I thought I’d hang out with the poets and my partner after that. It is a momentous step for which I’ll be forever grateful. And I hope you get to celebrate too, Chris. You have done a great job promoting and sharing poetry. When will your new book from the laureateship be published?

CT: Thank you, Robert! It’s been a life-changing opportunity being New Zealand’s Poet Laureate. I’m looking forward to having a bit more free time to finish the next book featuring poems from these past three years. Enjoy every moment of this National Poetry Day – I have no doubt you’ll be receiving lots of aroha and support during the day. I can’t wait to see all the great things you’ll do in the role and hope to share a stage with you somewhere along the way!

RS: Ngā mihi nui e hoa!