Street Art (+vlog)

By Renee Liang

I’m not a morning person. Like many, I find getting up early and going to work a real pain. So seeing a little cartoon bluebird spray painted onto a power pole one day helped entice me out of work grump. For months the little bluebird stayed in position on the pole, winking at me while I was stopped at the lights. I started dreaming about flocks of cartoon bluebirds landing on power poles all around the city, maybe even a painted jungle growing up around them. Then one day my birdy friend was obscured by a sprawling, ugly tag. And a few days after that, obliterated when the tag was painted out by people who no doubt found it as offensive as I did.

So, why is it that some things we call “street art” and some we call “crime”? And what made the council tolerate the little birdy, illegally spray painted, for months while the tag was painted over in days? Is there much of a dividing line between them, and if so, how does one tell the difference? And is having lots of street art a good thing?

Visting Valparaiso in Chile a few years back opened my eyes to the pleasures of street art. Here, street art has not only flourished, but actually made the city. Think of generations on generations of hippies building a city drunk on art and politics, and you start to get the idea – the buildings themselves are artworks. Here, street art defines the city and brings in tourists and pesos.

Closer to home, there are of course towns like Katikati and Tirau which promote their abundance of “street art” as a good incentive to visit. I’m aware we may be talking about a slightly different thing. Here works, which possibly started as one-off wacky outputs of local artists, are publicly condoned, commissioned and the subject matter pruned to affect local pride and the all-important visitors’ wallets. In contrast, the street art in Valparaiso started off as a spontaneous and somewhat joyous expression of anarchy and still retains that feel. To my mind this feels like the better “art” (with sincere apologies to the artists of Tirau and Katikati).

On flip side of street art, graffiti and tagging in certain areas have people muttering about dropping property values and getting in more police. So what makes street art good and what makes it bad? I’m not going to answer that question. I’m just going to talk some more.

Walking around Auckland, I’ve started noticing more stickers and stencil art appearing, and I’m enjoying the way it makes me more aware of my urban surrounds and more inclined to be curious about the spaces. There’s some real gems around the area, especially in Kingsland and Karangahape Rd, some by well known artists and others by artists yet to be recognised. To me, these works – not all of them lovely or easy to understand - are an expression of the soul of the city. I guess street art is more or less an extension of the deep seated human urge to respond or comment on our surrounds. In the old days that might have been in the form of romantic landscape oils or (older yet) cave paintings, but these days in the cliched ‘urban jungle’, we use appropriately ‘urban’ materials.

So, what is the difference between street art, graffiti art and tagging? As a nerd like me sees it, graffiti art’s position as one of the four pillars of hip hop now puts it in a rather confusing position. On one hand hip hop has morphed from being an urban response to what is now an established, lucrative and, dare I breathe it, mainstream industry. Designers and artists have picked up on design elements and are commercialising it, and this results in some jostling for space between the ‘real’ street artists and those attracted to the ideas and ethos, who are often also good artists. Unfortunately, this sometimes leads to some pretty ugly scenes over who is ‘legit’.

Although ‘tagging’ is still illegal and is, in fact being clamped down on by the authorities, ‘graffiti art’ is now highly sought after, commissioned and used for community projects by the aforementioned authorities. All of which can be rather confusing, as one Australian politician, the appropriately named Mr Pratt, found out recently.

In fact, it seems that the authorities are generally confused about street art: how to define it, how to regulate it and licence it. This is probably a good thing, testament to the protean and constantly evolving nature of street art, though it doesn’t help those of us who want to express our ideas but ensure that we don’t get arrested or fined.

“Street art”, ie art that is on the street, can be different to, but includes, graffiti art. Like the little birdy that lit up my mornings, it can take many forms and have many different intentions, from merely being whimsical to carrying a serious political message. It can take the form of stickers, paste-ups, posters, installations, stencils or tags and thus overlaps into the hip-hop territory I’ve already discussed. It can easily cross boundaries and become a world art project.

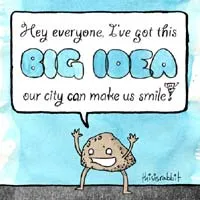

Since I’m merely an observer in this, not a practitioner (I hasten to add in the interests of maintaining my clean police record), I asked street artist thisisrabbit to meet me at a park bench for a suitably anonymised interview. He explained why he did his midnight missions:

“Things are just so grey these days. Is it not enough to make someone smile? Especially in the city, when you’re travelling around, it’s so easy to get into a pattern…. if you can find a tiny dancing rock somewhere or if you can see a cloud that’s got something to say, you might not like it but at least it’ll disrupt that pattern and hopefully get someone to question and… maybe that’s enough.”

His simplicity seems to make sense. Of course, others are drawn to other things street art can do, such as put across a political stance (hmm… maybe our politicians could take note? might be more effective than those gormless grinning billboards. Oh but oops, they made it illegal – I forgot). Street art can also point out a perceived injustice, celebrate beauty, make an artistic statement (how avant-garde) or merely mark territory. It’s all in the eye of the beholder. It can also make some people famous, as shown by the case of international artists like Banksy and our own local talent like Component who started their careers as fly-by-night street artists but now practise their art openly, drawing accolades from art galleries and commissions from admirers.

About now the question of profit and copyright turns up to sully everything. I’ve been following a local debate about an incident where a photographer exhibited photos of street art and then offered her prints for sale. Problem was, the photos she was selling as her own work (which technically it was) were close-cropped images of someone else’s work, a well known Auckland street artist. The street artist and his friends protested, and managed to get part of the exhibition taken down. But the photographer and her supporters replied that by putting his artwork (illegally) up in the public domain, he was renouncing his intellectual property rights and she was entitled to record it and disseminate it and in fact it was her form of tribute.

Fair? The reasoning seems a bit dodgy to me.

Even if the photographer was technically on the side of the law, morally this violates the idea of ‘collective sharing’ and ‘open access’ inherent in street art. I find this image a complete irony.

There are lots of perceptive comments, on both sides of the argument, on the sites I’ve linked to. Anyway, over to you, collective reading public. What are your views? I’d welcome your comments.

Anyway. It’s all getting a little fraught, and I’m sure my little blue birdy friend never meant to hurt any one in this way. Street art, after all, is just art. Better to let thisisrabbit have the last sweet word.

“I think the beautiful thing in NZ at the moment is that our street artists are making awesome works that have all of the soul of street art and the finish of fine art.”

Awww. Everyone, let’s go out and paint the town red. And green. And cloud-coloured. Legally, of course.

Image: by thisisrabbit