The biggest takeaways and the loudest silence at Nui te Kōrero 2025

Gabi Lardies attended the biannual arts leadership conference to take the temperature, glean insights and bring you sound bites.

From 8 to 10 September, 300 or so arts professionals descended upon the Mercury Baypark Event Centre in Tauranga. They came from all across the motu, as they do every two years, to gather for Nui te Kōrero, a conference held by Creative New Zealand. It is the largest national gathering for the arts sector in Aotearoa, and has been going for over a decade.

People, or their organisations, paid $90-$200 to attend the three-day conference, and yes, everyone got a branded lanyard and tote bag. We gathered in a big cavernous room which is sometimes a basketball court, and broke-out into smaller meeting rooms throughout the days. People were pleased to be there, suspended momentarily from their day-to-day responsibilities and amongst like-minded peers with plenty of morning tea biscuits and mini croissants.

This year’s theme was Kia kotahi te tū: Standing together for the arts. Messaging around the event promised things like “supporting the arts sector to respond to some of our biggest challenges”. The programme was curated by Ria Hall (Ngāi Te Rangi, Ngāti Ranginui, Te Whānau ā Apanui, Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, and Waikato), singer-songwriter, producer and political candidate from Tauranga, and Henrietta Bollinger, writer, playwright, activist and disability rights advocate and recipient of the Whakahoa Kaitoi Whanaketanga Creative NZ Artist Fellowship in 2023.

The programme had four areas of focus: equity and inclusion, accessibility, emerging technologies and creative economies. There were two full days of plenaries, panels and keynotes, which oscillated between boring, inspiring, overstimulating and tiring – all to be expected at a conference. I’ve scraped my notebook and recordings to bring you 10 of the biggest takeaways and one glaring omission.

The biggest takeaways

Jessica Hansell just might be the most inspiring arts leader in the country

Speaking publicly for the first time about the indigenous, independent, artist-led community space Wheke Fortress in Onehunga, Jessica Hansell (Ngāpuhi/Samoa) had us not only enthralled but also close to tears. She laid her heart open more than is to be expected at a conference, and her zingy poetic lines betrayed her roots as a songwriter (Coco Solid). A few stand outs: “overgiving is the hidden clause of being an artist,” “we are a building full of gay, indigenous, brown weirdos,” “what if we had a way to feel that level of intimacy and connection all the time, and we don't have to girl boss close to the sun in some weird bid to earn this wee treat called genuine connection?” and “aren't artists supposed to be fashioning a new reality, pulling from the heavens, so we have an interlude of it on Earth?”

To get your way, be prepared to pivot and persist

Self-professed ruthless realist Puawai Cairns (Ngāti Pūkenga, Ngāi Te Rangi, Ngāti Ranginui), who has been at Te Papa Tongarewa for 14 years and is currently the director of insights and audience, led us through some of her trials, tribulations and triumphs. Her kaupapa has always been to amplify the voices and stories of Māori communities, and this has rarely come easily. “I know that everything good is worth fighting for,” she said.

Of particular note was the battle Cairns fought for Māori stories to have prominence in Gallipoli: The Scale of Our War which opened in 2015 and still graces the museum. She kept being met with resistance and criticism – others thought that the coverage of Māori should align with the numbers who served, which would make them near invisible. “I did not want Māori audiences to miss out and not be represented,” she said. But the more she argued the less she seemed to gain.

Cairns almost threw in the towel but instead changed tack. “I hunted for and found other channels outside of the exhibition, adopting an approach that some might call multimedia dissemination”. She researched, wrote essays, did a TEDx talk, contributed to documentaries, wrote a book – “anything to get the Māori content heard or seen”. Then within the exhibition she took “different, less confrontational approaches” – re-coding the texts, and incorporating waiata, wairua, and carvings. “In the end, by stepping back from confrontation and finding a new argument, I managed to get more Māori stories in that show, as well as across many, many different channels”.

Karen Walker loves the NZ Opera

She may have missed the memo that she was speaking to arts leaders and governance rather than artists themselves, but Karen Walker was funny and charming and a pep talk, even if slightly off, is always welcome. One fun fact: she loves the NZ Opera and she especially loves The Unruly Tourists, a comedy written by Livi Reihana and Amanda Kennedy about badly behaved tourists leaving a trail of destruction.

The AI horse has fled the stable. So how should we ride it?

In a panel discussion, Anna Rawhiti-Connell, head of audience and off-platform strategy at The Spinoff; Lynell Tuffery Huria, commercial lawyer specialising in trade mark protection; and Michael Bell of Little Andromeda Theatre unanimously agreed that the AI horse has fled the stable. But what do we do with it? Rawhiti-Connell said we all need policies within our organisations on its use, Tuffery Huria said there needs to be better legislation, and Bell has wholeheartedly embraced it to cut down the bulk of admin work (and wages) at the theatre.

All institutions should have an access and equity policy, but most don’t

When Kaiwhakahaere Matua of the Tauranga Art Gallery Sonya Korohina (Ngāti Porou, Pākēha) asked her audience “Who's got an equity and inclusive policy in the organisation?” most hands stayed down, including her own. While her gallery has been shut for a two year redevelopment, the organisation has been reworking high-level operational aspects like their visitor experience framework. Korohina said that as they considered how to best serve and engage their audiences, equity and inclusiveness was embedded in frameworks. One example is a free art bus that picks up groups of students and brings them to the gallery. Their school programme was quickly booked out. Still, “policy is great, and that is the next step for us.”

Crip time and the Vā have much to offer

Interdisciplinary artist (and TBI contributor) Pelenakeke Brown (Gataivai, Siutu-Salailua) took the audience on a walk through art practices, including her own, that operate on and centre the experience of physical disability. Central in the works was the idea of “crip time”. Rather than bend disabled bodies and minds to meet the clock, crip time bends the clock to meet disabled bodies and minds. It is flexible, anti-capitalist and non-linear. She connected this view of time to the Samoan concept of Vā, and lent on Albert Wendt for a definition: “Vā is the space between, the between-ness, not empty space, not space the separates but space that relates, that holds separate entities and things together”. Many of the examples were fun – for instance in an exhibition called don't mind if they do, curated by Finnegan Shannon, the audience was invited to sit while a sushi-train-like conveyor belt brought tactile artworks their way.

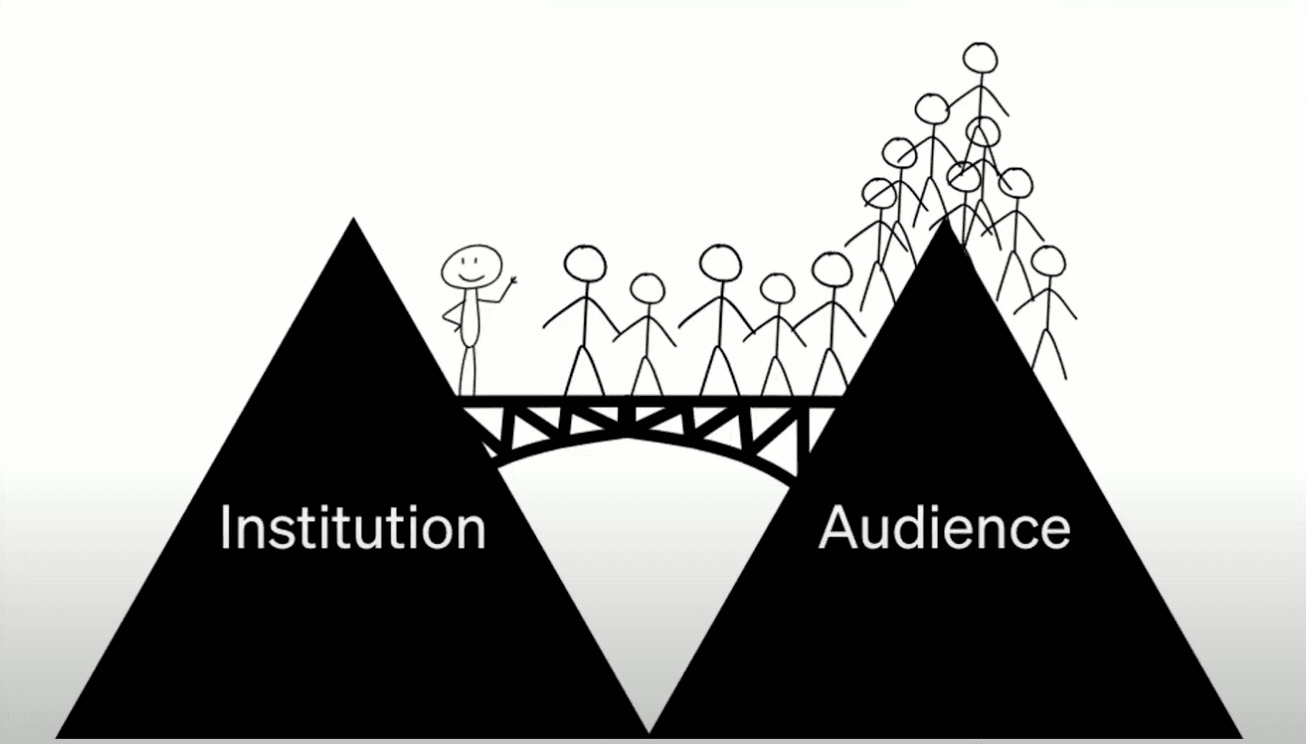

Get off your mountain top, listening to the institutional voice is now optional

Master of audiences and representative from an industry on fire (the media) Anna Rawhiti-Connell came to tell us to get off the mountain tops that we yell at audiences from. She attempted to confront the “harsh realities of a difficult situation while maintaining unwavering faith that you will ultimately succeed”. The harsh reality is that audiences have more power than ever before, are more fragmented than ever before, and are “wondering why we're still shouting at them.” She thinks that reaching people online requires a mindset change, talking to and with them, not at them, and making things “not about us, about them”. It seems we should play into the fact that “people are desperate for connection, experience, transparency, meaning and most of all, to be seen” in order to get their attention.

We need dedicated placements for disabled ākonga in tertiary performing arts courses

Duncan Armstrong, a dancer, actor and advocate with Down’s syndrome spoke about his busy career and what it can be like to navigate the world with his disability. He has won multiple awards including Best Performance at the 2018 Auckland Fringe Festival for his solo show, Forcefield. Armstrong is a “mainstreamer” meaning that he believes disabled students should have equal access to public education. After high school, Armstrong did a foundation music course at Whitireia but they wouldn’t accept him into the certificate course. He then applied to Toi Whakaari: NZ Drama School, but wasn’t accepted there either. Instead Armstrong had to travel to London and Australia to learn at inclusive arts companies. He says that there should be dedicated spaces in our tertiary performing arts courses for disabled students.

Audio description is a beautiful art in itself

When Nicola Owen, one of Aotearoa’s first professional audio describers, shared her audio description of Fred Graham’s Manu Torino sculpture I was struck. Her words heaped more beauty and context on the piece than the photos of it projected up on the screens. Audio description, while always standing alongside other artworks, is an art in itself, argues Owen. It turns visual context into words for people who would not otherwise be able to access it, and creates images and meaning in people’s minds. Not only is it an art, but it's one rooted in human rights. “Blind people have a right to engage the world through the arts,” Owen succinctly said.

Art for art’s sake is no longer resonating with philanthropists, sponsors or donors

Philanthropy has always been strong in the arts, but it is in decline, and it is changing, says Sharon van Gulik, who has spent many years finding funds for arts organisations and kaupapa. She says that arts must offer more than a transactional exchange and consider purpose-led partnerships as people are seeking impact-led giving. This means more entangled relationships with donors, ones that involve shared visions, mutual trust, open communication and a long-term focus on delivering a positive impact. Van Gulik framed it as all great and positive, but at least one person in the audience worried about how much power this could give the people holding the money.

The loudest silence

Four months into her role as Creative New Zealand’s chief executive, Gretchen La Roche stood in front of representatives from the sector for the first time. The crowd was deathly quiet – not a titter nor a whisper. The one-sided silence felt expectant. She pointed out the “difficult” operating environment, the “tough time” we find ourselves in that “could be seen as a hostile environment for the arts”. There were no specific named enemies of course, just economic pressure, global uncertainty and conflict and the rise of hate and race based crime. The usual suspects that she thinks are likely “be with us for some time”.

There was perhaps no more telling moment during the whole conference than 16 minutes into her speech. “The demand on funding, as we all know, is incredibly high,” she said, acknowledging that just a few days prior, it was announced only 34 of 183 eligible applications were funded from the CNZ Arts Organisations and Groups Fund. The total amount of money given was $1,435,660 – about 13% of the $11,222,144 that was asked for. Despite the fact they couldn’t fund everyone, she wanted organisations to know that, “we stand with you”. And that’s when someone laughed. The audience’s veneer of politeness cracked at the absurdity of the statement. La Roche continued on, saying that difficult times often produce great art, like Picasso's Guernica.

That is how the biggest absence at the conference flickered in, and out, of view. I heard that people were frustrated that the biggest crisis in the sector wasn’t addressed. There is simply not enough money in the pot, any pot. Some attended the conference with hopes to get more information on the expanded Arts Organisations and Groups Fund which is set to replace the Tōtara and Kahikatea funding, but this did not come. It's thought that the change to a new funding structure will spell a mass extinction event for arts organisations and groups. It is looking not like a difficult time, but a very real existential threat. Kōrero about this was absent. Support to manage or survive this threat was missing. Instead it seemed we were talking details and tinkering around the edges of operations.

“It's important to note that your importance and the importance of your work is not marked by success of funding,” said La Roche. But for many in the room, funding means more than importance, it means existence.

When looking back at photos from Nui te Kōrero, there is one that sticks with me. It isn’t of a speaker – it isn’t even at the conference venue. It’s from the field trip hosted by ngā Iwi o Tauranga Moana, who took participants on a walk through notable sites near the shore. A big group of people are gathered on the grass. Behind them Mauao (Mt Maunganui) is visible over a stretch of sea. The people, standing closely together and wearing their lanyards, are squinting into the sun and smiling at the camera. Their hands are up as if the photographer has asked them to be silly. They are many, and they look happy to be there.