The Truth Will Guide the Way

Written by

To celebrate International Women's Day 2021, The Big Idea is revisiting some of the stories that recognise Aotearoa's leading wahine toa of the arts. Please note, this story has been edited to make the dates accurate to the present.

Nikau Hindin is a resourceful, natural force to be reckoned with.

Of Ngāpuhi and Te Rarawa decent, she spends her days reviving the ancient art form of aute, Māori tapa cloth.

It is believed to have been over a century since aute was practiced by Māori, but after a journey to Hawaii, Hindin learned how to beat Kapa (Hawaiian tapa cloth), and learned from faculty head of the University of Hawaii, Maile Andrade, the little known history of Māori aute.

“It is the type of practice that takes up a lot of time and resources and it isn’t just about having one skill. There is the making of the tools, there is sourcing pigments, there is gardening and harvesting, there is the physicality of beating, then the quietness of painting and the study I do on the stars for my star maps. It is all-encompassing and that suits me as an artist. I think that every decision you make in life also contributes to the art you make, from the food you eat to your morning routine. Nothing is separate in art.”

Hindin crafted her first tools from pohutukawa and kauri wood, using an adze (bladed tool), hoanga (sandstone) pipi shells and sharks teeth.

After harvesting the aute plant and beating the fleshy inner bark, it transforms into a paper-like material, which Hindin then paints star maps on. The process is intensive and intricate, but the results are exquisite.

Cook the ‘Antagonist’

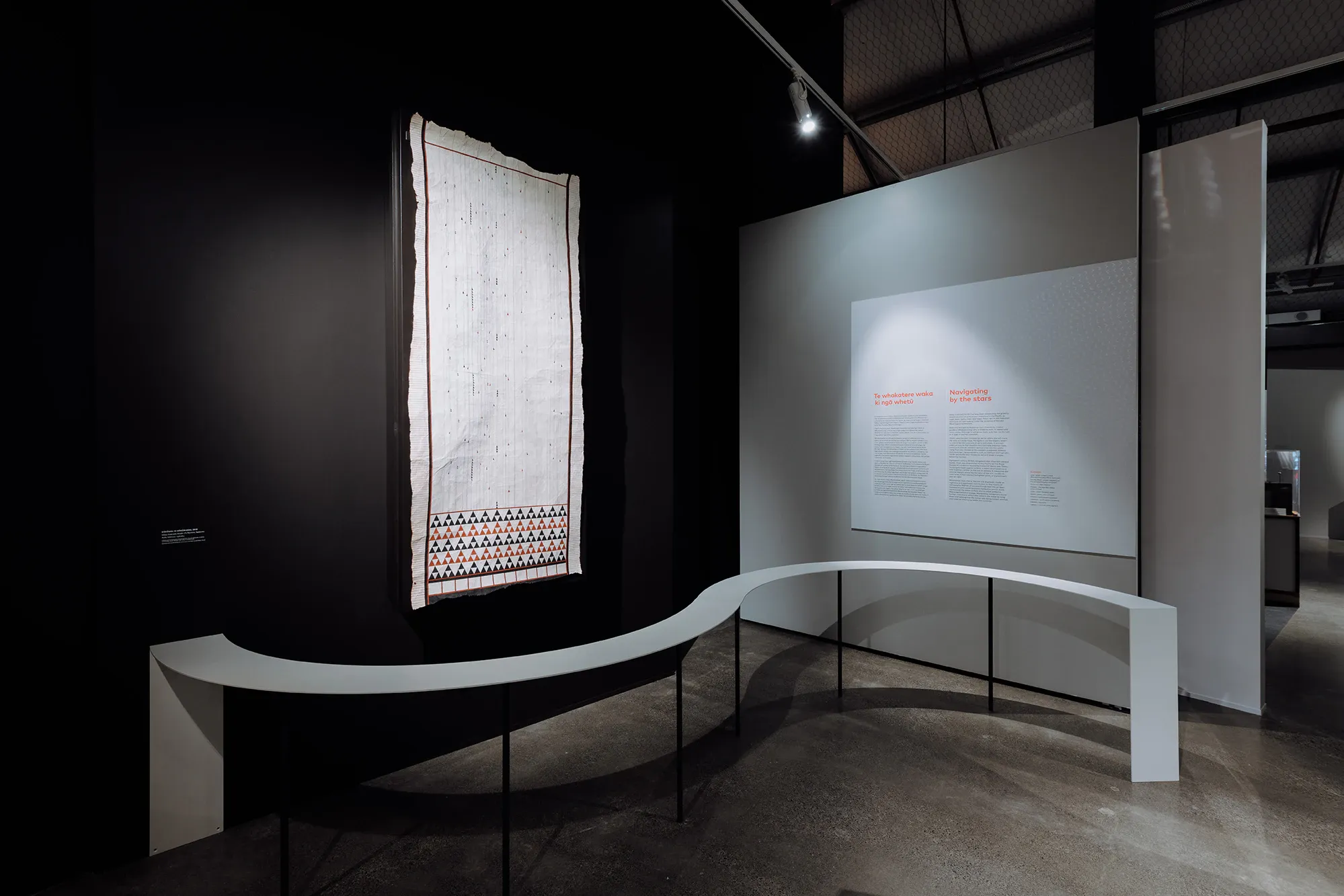

Hindin’s largest piece to date was on display at the New Zealand Maritime Museum Hui Te Ananui A Tangaroa. Alongside 6 other artists, it was part of the exhibition Tākiri: An Unfurling, in which the artists explore early Māori and European encounters some 250 years later, continuing on from the nationwide Tuia 250 commemoration.

Nikau Hindin’s work, an eye-catching part of the New Zealand Maritime Museum’s Tākiri: An Unfurling exhibition. Image: David St George

Nikau applied to be a part of the exhibition because “it was about including Māori stories into this narrative about Captain Cook. I felt it was important that our navigational stories and frameworks were included, that we actually sailed here long before Cook did.”

Hindin’s work focuses on observing the skills of our ancestors, and this means renown Polynesian navigator Tupaia is essential to the whakapapa of her work. Cook, on the other hand, is more of an “antagonist”.

“He got all the glory as the man who ‘discovered New Zealand.’ He didn’t discover anything; he was just a man who turned up. The feat of this voyage to Aotearoa and settling all of Te Moana Nui a Kiwa (the Pacific Ocean) is the equivalent of ‘Man landing on the Moon’ in terms of technology of the time. Our ancestors are the real unsung heroes and adventurers.”

An audience listens to Nikau Hindin talking about her mahi at a late night event at New Zealand Maritime Museum. Image: David St George

Redefining our identity

Providing an artistic interpretation of our history of European contact is complex and is invasive for many Māori. I asked Hindin how we, as Māori and Pacifica artists, commemorate and honour the past whilst dealing with the emotional trauma that comes with projects like Tuia 250?

“It is very painful. I’m lucky to have learned about my taha Māori (Māori identity) from a young age, to have learned about colonisation at primary (school). My ability to cope has developed over time but some people go through the process of decolonisation in their twenties and naturally feel very angry. I can have conversations with racist Pākehā now and not cry or get mad but it has taken many years.

“On the beach at the Pōhiri for the Endeavour, exactly 250 years after he killed Te Maro, I am assaulted by a seemingly friendly Pākehā lady. She tells me she loves my artwork but why are all the Māori protesting against the Endeavour ‘they just don’t understand.’

“She tells me she loves the Native Voices Exhibition at the Gisborne Museum which includes over 50 works by Māori artists… but why do Māori get a free ride into Med School and Law School? Again, she loves my artwork but Māori killed off all the Moriori.

“We have been fed convenient mistruths to justify colonisation, land theft and the impoverished state of our people today. I try to explain this all carefully and even convincingly now but at high school I was having heated arguments with my classmates about Shakespeare’s The Tempest, then storming out of class.”

The hope for this exhibition and Tuia 250 in general is that a dialogue will be sparked and Aotearoa will confront its deep-seated racism.

A close up look at the symbolic blue beads from the start of the Tākiri: An Unfurling exhibition. Image: David St George

Significance of the Blue Bead

When entering Tākiri: An Unfurling, one can expect to at first feel a dimly lit space. Hindin’s star compass might be the first thing one sees, as it is near the entrance, and if you bring a small taonga, it is a rolling trade - you could potentially exchange it with one of the 32 objects featured on her piece.

Hindin uses the star compass with each star house represented by a blue glass bead. “The star compass, first of all, is the conceptual framework for the way our ancestors navigated to Aotearoa using the currents, winds, waves and stars. It is a multi-dimensional tool, placing the waka at the centre, the horizon is the circumference and everything that goes through or over the compass is absorbed and calculated.

“The second dimension to the compass is the blue glass trading bead. In remembrance of the first-ever encounter between Māori and Pākehā, Cook’s crew killed Te Maro, a chief from Ngāti Oneone, a hapū of Ngāti Porou. After they shot Te Maro dead, Cook left some blue glass beads and nails on his body and I recreated these beads because it’s important to remember this murder.

“The fact that many don’t know about this just exemplifies the racism entrenched in our country.”

Nikau Hindin soaking in the finished product in the Edmiston Gallery. Image: David St George

All the beads are gone now, exchanged by friends and whānau visiting the exhibition. “The trades are unpoliced, the value of the trades are not judged, it is up to the individual, it is about power. I wanted to make one art piece that could not be owned.”

Hindin has two works in the show. The second one hovers over the star compass. It records the time of Matariki, and the times stars rise and set, speaking to the Star Compass on a two dimensional scale. Along with the six other commissioned artists, Hindin’s work has been acquired into the Museum’s permanent collection, lending complexity and perspective to the stories of Aotearoa’s history.

“I’m really proud of this piece. Hopefully it will be shown in other galleries too one day.”

Art is Life

Hindin believes that art is everything and anything.

“Art is the way you live your life. It is your tools, your garden! Your commitment to the Maramataka (Māori lunar calendar). It is raising money for a good cause. It is activism. It is joining the cultural revolution. It is learning your mother tongue. It is choosing to only eat the protein you’ve hunted.

We need to move past this idea that art is just paintings on a wall. Art is so much more

“Art is a series of decisions made with intention. From then on, it is the mana you give it, the words you use to describe it, how to tell the story - that’s what makes it art and helps other people experience it with you.

“I think we need to move past this idea that art is just paintings on a wall. Art is so much more and we have so many talented artists among us! It’s just about having the confidence to call it art and then pushing the boundaries of the Eurocentric art world.”

Nikau Hindin proudly displaying her mahi toi at the exhibition ‘names held in our mouths’ at Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery, 2019. Image: David St George

For now, Hindin is focussed on the present, meeting deadlines, working with her traditional practice. When she looks into the future, she sees teaching, harvesting, manu aute flying around everywhere. She sees kākahu (clothing) and whare (buildings) filled with aute.

“The dreaming is endless, but right now, it is just one step in front of the other.”

This story is written in partnership with the New Zealand Maritime Museum Hui Te Ananui A Tangaroa to celebrate Tākiri: An Unfurling.

Story by Jessica Thompson Carr