Turning Unhappy Customers Into Allies

Unhappy customers can be a cause of genuine grief for individual practitioners and companies in the arts industry.

For as long as Perth arts devotees can remember, PICA (Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts) has had the most uncomfortable theatre seats west-side of Sydney.

“Our performance space seats outlived their welcome a long time ago!” PICA’s General Manager Georgia Malone tells ArtsHub.

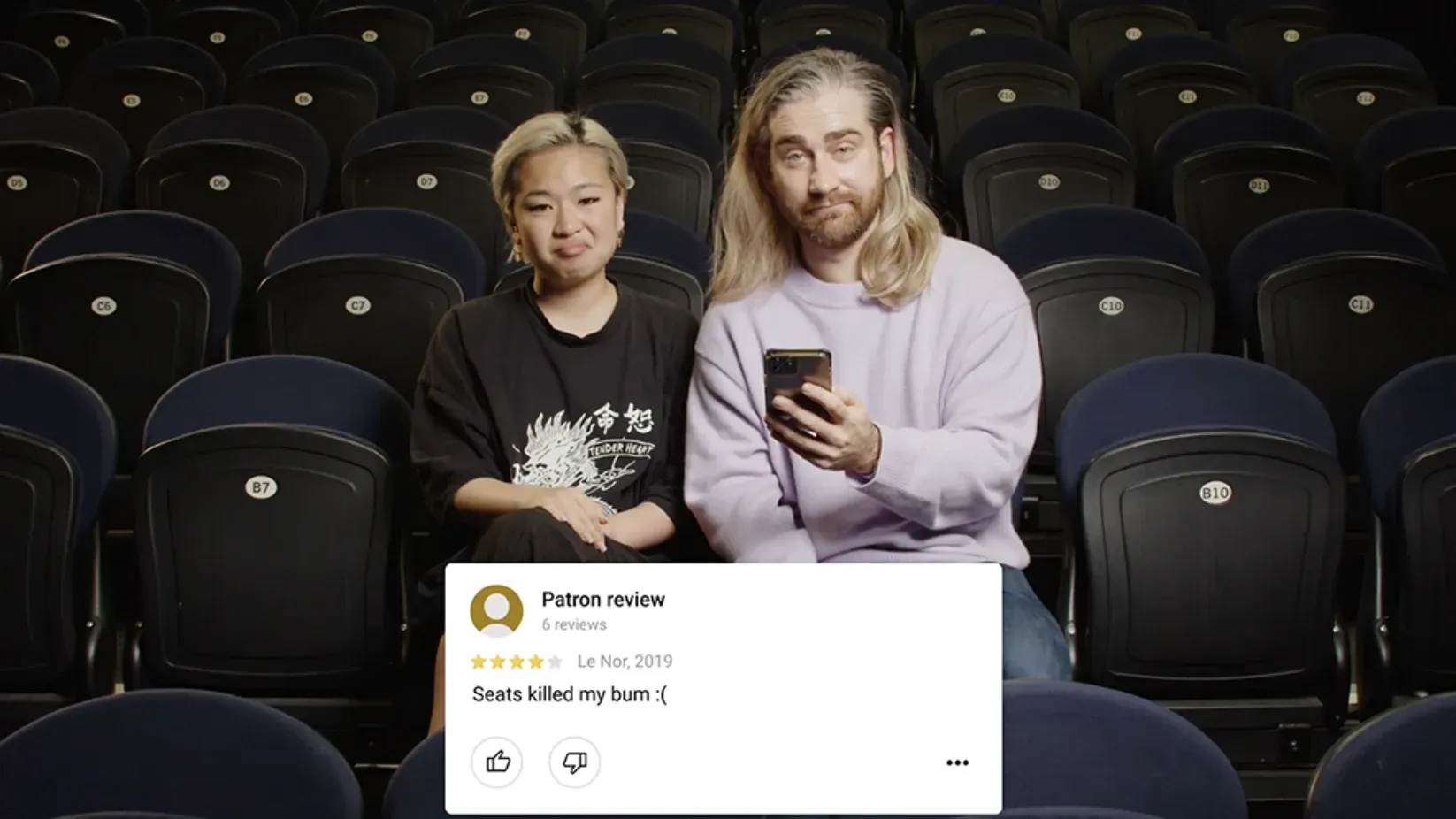

After numerous complaints from frustrated patrons forced to watch exciting new art on back-breaking seating, PICA is now turning its worst-ever reviews into fundraising gold.

PICA’s ‘No Numb Bums’ campaign is using ‘cheekiness’ and humour to drive support for new seating and fix one of its most complained-about problems.

Malone says the campaign’s success so far is built on its playful twist on a well-worn formula (the ‘buy-your-own-seat’ strategy), but it’s also about PICA’s honest and transparent approach to the problem.

“It’s clear that we are owning it rather than ignoring it,” says Malone.

“We’re basically saying to our audiences, ‘We know, we hear you, we’re trying to do something about it’, but we’re bringing them along for that ride with us,” she continues.

“Essentially, we’re solving the problem with our audiences’ involvement and we are doing that in a fun and open way.”

Is the customer always right?

While spotlighting bad reviews is working well for PICA, it’s a nuanced strategy that does not suit all customer complaints.

For a broader view, General Manager of Ticketing and Customer Feedback at the Sydney Opera House, Steven Baillie has some valuable advice.

Baillie says that effectively handling complaints is often done case-by-case, as no two situations are the same. However, there are some good general strategies to follow to ensure unhappy customers return as loyal fans.

“One of the most challenging complaints we get is around audience behaviour during live shows – especially around use of technology,” Baillie explains.

“Those cases are challenging for a number of reasons. First, people can have different expectations around theatre etiquette, then depending on where the person is sitting in the theatre (end of row or mid-row), it can be hard to achieve a good outcome without causing further disruption.

“So in those situations, it’s essential to exercise good judgement and be sensitive to specific conditions.”

But if the Opera House receives a post-show or post-visit complaint, a personalised approach is essential to a good outcome.

“We make sure we investigate the customer’s issue and get evidence from all sides so we can take an empathetic view,” says Baillie.

“Then it’s about picking up the phone,” he adds, signalling that this supposedly old-school tool will continue to play a powerful role when it comes to quality customer service.

“Those calls can be interesting, because sometimes people say, ‘I can’t believe you actually called! I expected an email’.

“Then they might say that at the time they made the complaint, they were feeling a bit upset or angry, but that they really appreciate us looking into the issue.”

Turning complaints into value-adds

Tuning in to customers’ needs is key to many complaint resolutions, but Baillie believes this attention to detail can also add value to the company itself, and can be used to pre-empt future customer experiences.

“We’ve started what’s called a ‘Voice of Customer’ program,” he says.

“We have a group of Sydney Opera House’s executive staff who dig through our public feedback, analyse it and use it to guide decision-making.

“This allows us to continually monitor public sentiment and use it strategically to guide our improvements.”

In a similar way – though not quite on the same scale – Perth-based theatre company Spare Parts Puppet Theatre has also used audience criticism to add value to what it does.

Artistic Director of Spare Part Puppet Theatre Philip Mitchell says “one year we got comments on our post-show surveys saying things like, ‘Not enough puppets’ and ‘Where are the puppets?’.

“But that was really important feedback because it made us realise that for some of our more contemporary work, we needed to better prepare our audiences for what they were going to see.”

Subsequently, Spare Parts produced a series of fun YouTube explainer videos on topics such as Object Theatre and Body Puppets to better prime its audiences for the diverse range of puppet theatre it offers.

“The videos worked really well,” Mitchell divulges. “And we wouldn’t have thought to do them if we hadn’t received the direct feedback.”

Coping with criticism in the workplace

Dealing with criticism from customers is one thing, but what about negative feedback on your performance on the job?

Human Resources Manager at the Australian Chamber Orchestra, Claire Diment, says there are a number of good ways to handle difficult professional feedback in the workplace.

1. Don’t get defensive: “Although it’s understandable that our first reaction is often to get defensive or angry – try not to.”

2. Listen first, respond later: “It’s essential to listen carefully to the feedback, as difficult as that may be.”

Diment adds, “And remember that you don’t have to respond immediately. You can ask for time to reflect on the feedback, which may be useful if you are upset in the first instance.”

3. Ask for specifics: Asking for suggestions for improvement is also important, “so that you can be clear on what you need to do to follow up with the necessary changes,” Diment suggests.

4. Lean on your support network: You’ll no doubt feel vulnerable after receiving professional criticism, so make sure you have some touchstones of support around you, so you can debrief.

“Internal resources in HR or EAP [Employee Assistance Program] could help,” Diment says. “Or external people, like friends and loved ones can be good to vent to.”

Ultimately, one of the keys to handling negative feedback about your work is to realise it is not casting doubt on your entire character or judging who you are as a person.

As Malone at PICA advises: “It’s not personal. It’s about your performance in your job; it’s not saying you’re a bad person.”

This article was originally published by our friends at Artshub Australia.

Written by Jo Pickup.