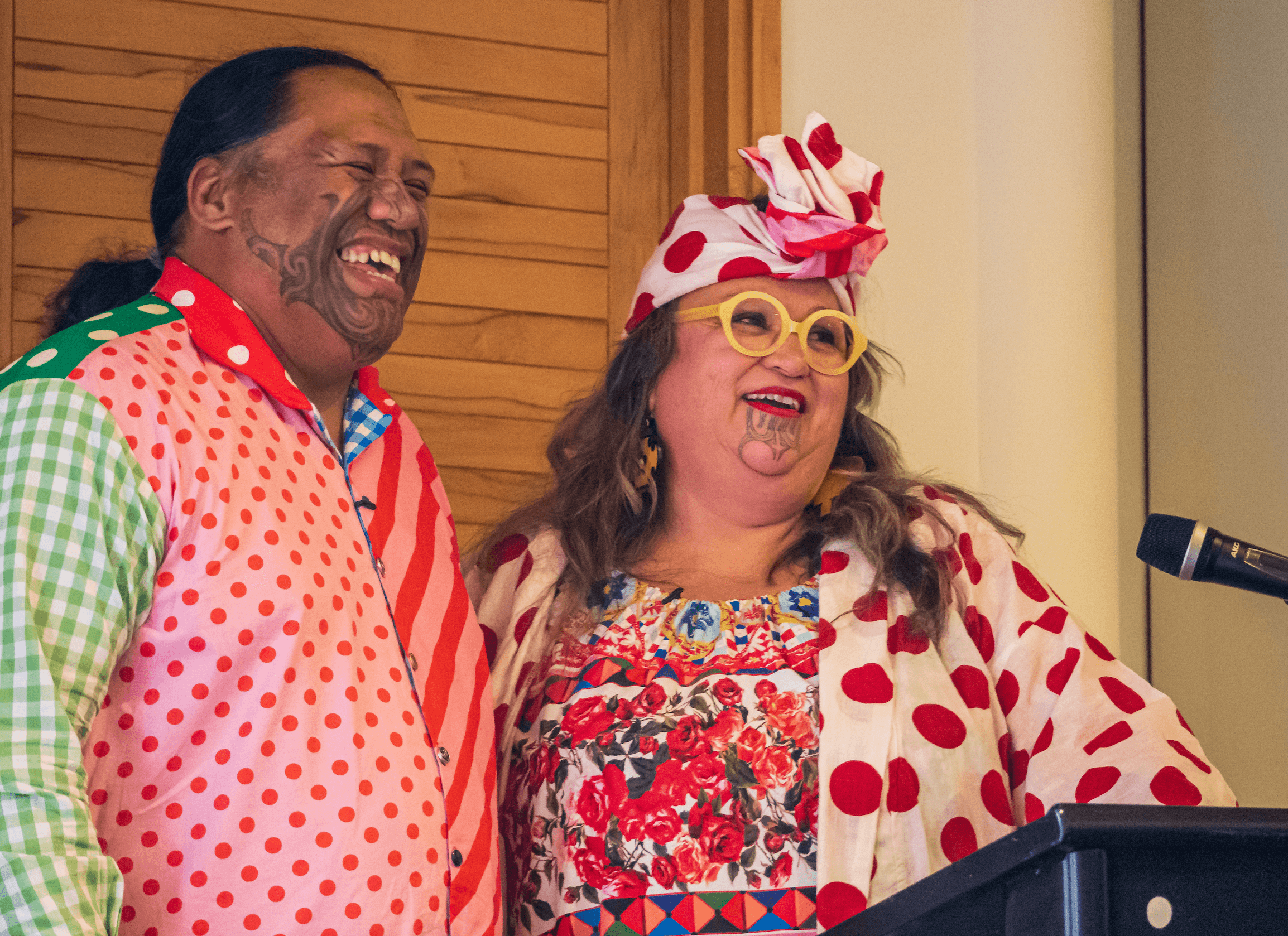

Tuupuna-Inspired Light – Lissy & Rudi Robinson-Cole's Unrelenting Vision

One of the success stories of Aotearoa's creative community in 2023 has been the completion of the touring Wharenui Harikoa - Jack Gray looks at the journey, impact and challenges the artists faced along the way.

The artistic expression of Lissy and Rudi Robinson-Cole is drawn from a highly emotive connection to their core values as Māori creatives in this time period. The context of Toi Māori art is both infinite and limited, as evidenced by their funding assessor’s feedback at the start of their journey towards envisioning the massive full-scale crochet Wharenui Harikoa.

Upon reading their unrealised artwork, the assessor commented that they were unsure where it sat on the`Māori scale’, suggesting the uncomfortable terrain of locating Te Ao Māori as a thing of the past, as opposed to a thing of the unknown future.

Māori culture is an anomaly in that sense. On one hand, it prides itself on known whakapapa, tracing histories, connections, land and ocean scapes, songs, stars and ephemeral beingness. On the other, it can easily be tokenised, a useable, discardable, entity that participates in our history of cultural confusion (as seen recently in the Government’s absurd – but cunning – focus on displacing the mana of our official language, moving agency names in Te Reo behind the English counterpart).

This ‘Māori scale’ then becomes the sliding barometer of righteousness on all sides, from the heroic (the recent vandalism at Te Papa culturally calling out the hypocrisy of the Treaty of Waitangi English version as ‘equal’ to the Te Tiriti o Waitangi) to the cringe (The Prime Minister benefitting from taxpayer Te Reo lessons whilst setting out to cancel these subsidies for others).

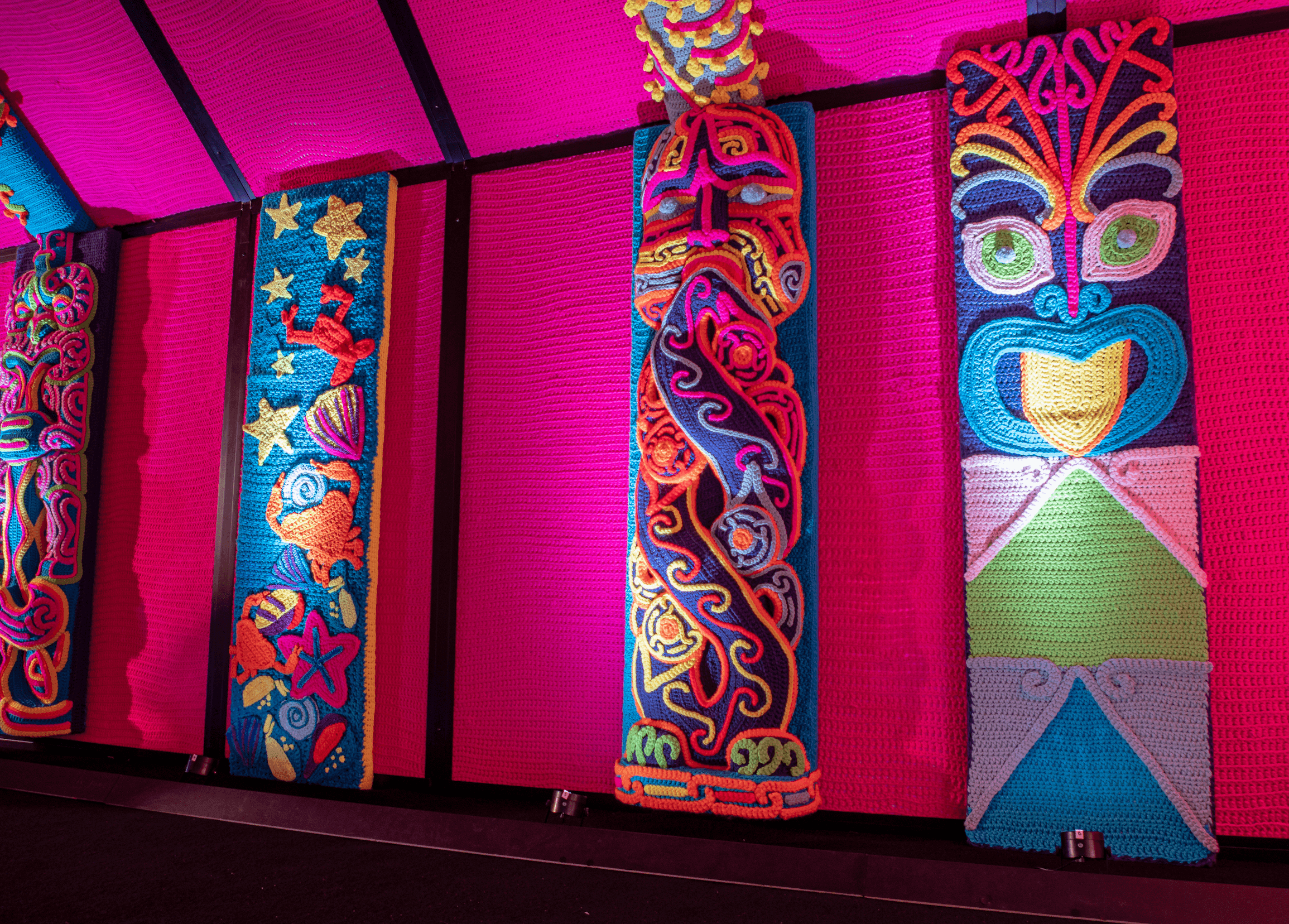

The key phrase for Wharenui Harikoa has been “Ko Wharenui Harikoa he poro whaka hakoko ko Uenuku tawhana ki te Rangi – Wharenui Harikoa is a refracting prism of tuupuna-inspired light that shines across the sky like a rainbow.”

Part of manifesting this vision for the Robinson-Coles included wānanga with a trusted cohort of supportive Māori collaborators - the Harikoa Hoa - made up of dance artists, crochet artists, carvers, art curators, art producers, taonga puoro artists and cultural consultants, all who manoeuvre around this kaupapa in ways that bridge the pathway to enlightenment, cultural tikanga and notions around how a new expression unfolds collectively.

As the primary artists, Lissy and Rudi have taken on other realms of cross-pollinating, where they have had to imbue their set of responsibilities with protocols as kaitiaki of the Wharenui. This has included endless email trails with presenting partners, museum institutions and art galleries, who work with these talented creatives (and their Harikoa Hoa) on defining the parameters of interactive engagement.

Are audiences allowed to sing in the whare? Are they allowed to lie down? Are kids allowed to run around freely? Do visitors have to remove their shoes? These questions are largely answered generically, as the Wharenui is both an activated House of the community, where life and death platforms hover liminally in the vortex of the Whare, whilst it retains the provenance of a taonga held within the esteem of museum curation.

Lissy and Rudi have the unique distinction of creating a Wharenui, the first in their materiality – which answers the original question of where it sat on the Māori scale. Quite frankly, it didn’t and its now existence has lengthened that scale somewhat considerably.

This development of material culture in a modern Aotearoa is where truths become undeniable. All wharenui previous to this one were made to signal the turangawaewae, the tangible signposting of ancestral standing place. They were made to be instilled into the earth, whether traditionally or in a modern context. The fabrication of how Whare belong in the world today, where we can enact our beingness as Māori, leads to questions around whether Marae can be built in the lands of the Gadigal, in Sydney, where generations of ex-pat Māori have migrated to and where they plan to stay – albeit on other unacknowledged First Nations lands.

These types of discussion typically fall into three categories. The first category being Māori people who want something so much that they validate it customarily and make their claim unwavering and resolute. The second category are those who see multiple sides and perspectives and therefore are less likely to align with a binary approach. The third category are non-Māori weighing in with their ideas and their lack of cultural understanding. Across these varying fields, we see the contestation of ideals vs. privilege, the process vs. progress, and the differing perspectives backing the worldview under question.

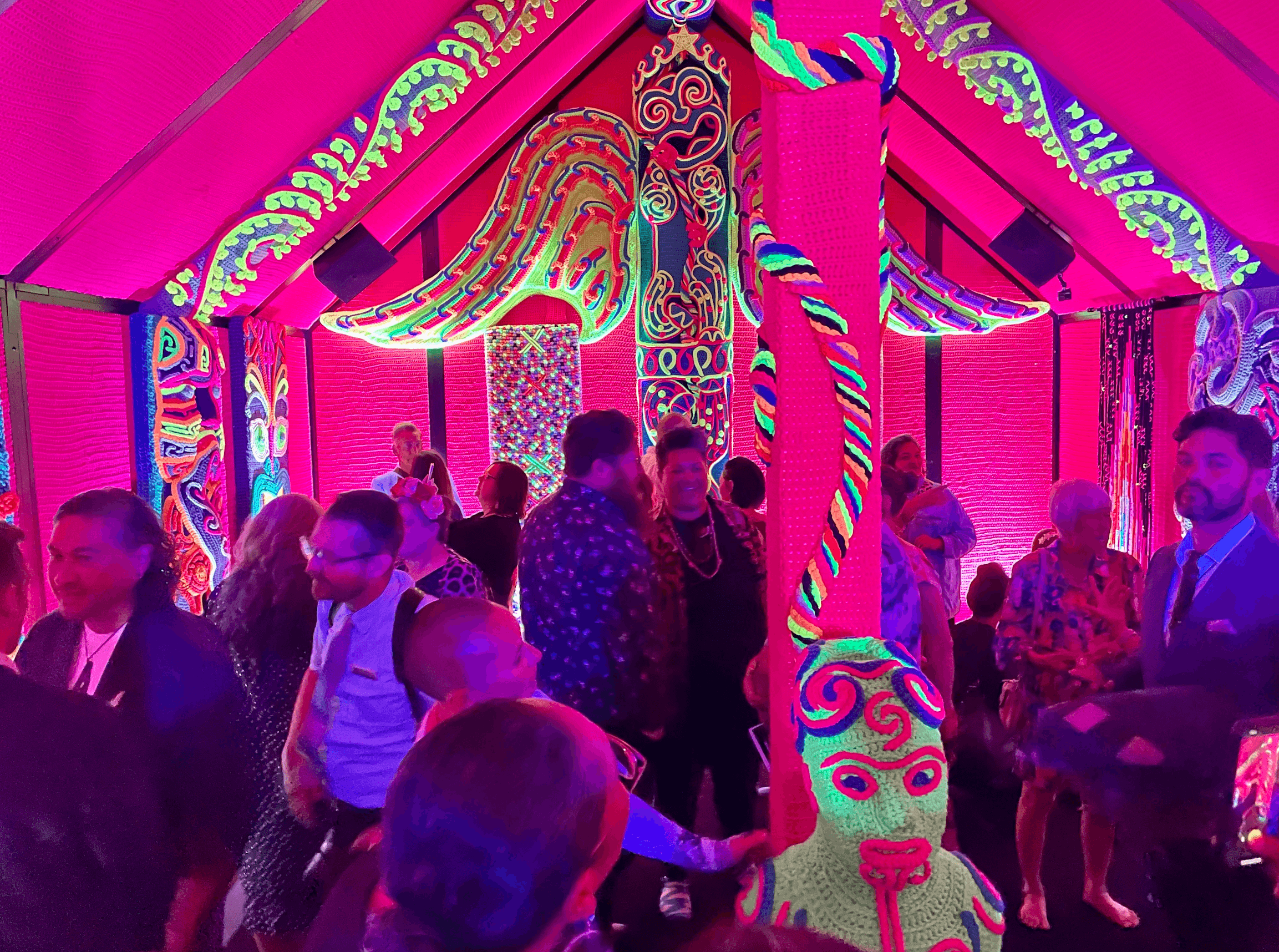

Lissy and Rudi’s Robinson-Cole's journey towards the November 30 opening of Wharenui Harikoa at the Waikato Museum included dialogue with Museum programmers, curators and kaitiaki, to figure out the procession into the gallery space holding the Wharenui. The issue of audience numbers played a part in both the private opening as well as determining how the multiple realms of tikanga and performance aligned.

Any of the entities wanting or demanding absolute autonomy were left on pause, as the logistics of assembling the house for the first time, creating a synchronised light and sound show, editing and completing a dance film, and interweaving all of the performative elements of dance, oratory, music, song and ensuring this all played out in real time fitting 150 (over capacity regarding sightlines into the house from front on) were all factored.

It was the sum of the whole, and a huge amount of trust by Lissy and Rudi that this Wharenui was being guided by higher powers, who had been the orchestrators of the entire vision. Suffice to say, it was saved from calamitous hi jinks by a cultural grounding. Māori see, feel and follow. It is the tikanga of trust that is interwoven in all protocols, and this opening was no different.

The wairua was palpable, the sounding of the pūtātara, the karanga, the taking off of shoes, the entry into the doorway to see Wharenui Harikoa in UV light, bright neon forms piercing the eye, bodies crammed sitting, on the floor, on demarcated chairs for elders and VIP, and spilling out to standing space at the back and sides.

As the rules blur, the vibrations bend, the timed schedule dissipates and the unfolding – which is the genius of cultural artists like Lissy and Rudi – unpacks all of the trauma, the tears, the whānau raruraru as equally as it sharpens the intent, the heartfelt, the waiata tautoko, the embraces and the celebrations. It is here, in the midst of the rainbow and the reality, where joy excavates from aroha, the held breath to self-sustaining life force.

On opening night one of the Harikoa Hoa said “this Wharenui makes me think we are going to be OK”, as the plans of the Government give rise to fears regarding amendments to Waitangi Tribunal legislation amongst other Māori abolishments. These feelings reverberate with uneasiness, making people wonder what the amorphous ‘Māori scale’ looks like.

Will there be depth to increase the ways in which Te Ao Māori retains its mana and the advancements of cultural innovation that are as yet unknown?

In any case, Wharenui Harikoa continues with its aim to manifest intergenerational healing and deeply felt joy, one loop at a time, connecting all people and igniting joy globally.