"Upsetting", "Deeply Concerning", "Laughable": NCEA Shake Up's Impact on the Arts

Arts teachers are used to asking questions of their class. But it's not the students - rather those who govern their profession - that they want answers from.

A petition has been organised, formally requesting the House of Representatives to "urge the Government" to stop a proposal to reduce the specialised art subjects that it claims "will damage the opportunities" of school students across the country.

So what's happening?

Among the Ministry of Education’s proposed changes to the NCEA curriculum, the elimination of Classics, Art History, and Latin at level 1 has received a certain amount of public attention and media coverage.

But as revealed by a Ministry of Education consultation survey, there are other changes proposed to the “arts learning area” at level 2 and 3 that deserve scrutiny, not least because of the lack of clarity around what they entail:

-

Develop two subjects for Music (Music Creation and Music Representation)

-

Combine Painting, Printmaking, and Sculpture into a single Visual Arts subject that provides flexibility for ākonga [students] to explore multiple visual artistic media

-

Expand Photography to include both static and moving image

-

Introduce three new subjects: Mau Rākau [traditional Māori and other indigenous martial arts], Raranga [finger weaving], and Whakairo [carving]

These proposals have sparked distress among many of the country’s art teachers.

Reading through the information provided by the Ministry, a pattern emerges of either de-emphasising the importance of technique and theory in favour of creative expression and/or future employment.

Visual Arts are defined as:

“…ākonga explore, refine, and communicate their own artistic ideas by selecting one or more Visual Arts disciplines and responding to how art expresses identity, culture, ethnicity, ideas, feelings, moods, beliefs, political viewpoints, and personal perspectives. Through engaging in Visual Arts, ākonga learn how to discern, participate in, and celebrate their own and others’ visual worlds.”

Noticeably there is little mention of visual communication, the intellectual discipline of composing an image or object, drawing, creative problem solving, or an acknowledgement of the technical theory involved.

Design has been “unbundled” from the “Visual arts assessment matrix”, though this is understandable given how much design has grown in the past decade and overlaps with technology studies.

In the case of Music, the theory and practical become two separate subjects entirely.

The Ministry justifies the merging of Printmaking and Sculpture with Painting by pointing to the relatively low enrolment numbers for the former two subjects, and:

“The single broad Visual Arts matrix provides limited opportunity for different visual arts disciplines to specialise, but also ensures a strong common understanding of the cross-cutting strands of the Arts.”

Art of the matter

This argument broadly parallels the interdisciplinary model adopted by some tertiary institutions – such as Elam School of Fine Arts at the University of Auckland – but not all. The University of Canterbury’s School of Fine Arts retains separate departments for now.

In the case of tertiary art education, these amalgamations have often been cost-cutting measures in response to shrinking budgets and an obsessive focus of the Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) subjects.

That issue is an international one, and in the US has led to the widespread elimination of full-time specialist art teachers in favour of part-time generalists in public schools.

Roger Boyce, a former Painting lecturer at University of Canterbury School of Fine Arts knows full well, having previously taught at Princeton, Carnegie Mellon, Western Washington University, and Smith College in the US. He observes “full-time art teaching jobs in the US have gone the way of the dodo. Every academic contagion grown in the USA eventually infects these shores.

“Teaching of the arts is seen - in administrative suites - as less preparing nascent artists for a vocation and more as a sort of Victorian Era enrichment exercise for the STEM-excelling children of aspiring-farm-service-town burghers.”

Picture not perfect

Photo: Jon Tyson/Unsplash.

Naturally, there are practical issues with requiring teachers to teach a variety of technically specialised artistic disciplines. Still photography and moving image, for example, are hugely different forms aesthetically and technically.

“Painting requires a vast understanding of composition, technique material knowledge, what grounds and paints to use and how to use these,” says Amy*, an art teacher at a regional North Island high school who wishes to protect her identity.

“Sculpture requires material knowledge,” Amy elaborates, “thinking in the round and how light and shadow effect the work. Printmaking requires material knowledge, techniques and tradition knowledge, specific resources, inks, plates, presses and in some cases acid baths.

“They are all vastly different and very much specialised subjects; they really need to be left as individual subjects in the senior years at school.”

Making a video work encompasses many different skills in terms of scripting and editing that composing a photograph does not, despite both using cameras.

A spokesperson for the Ministry of Education responds that in the current proposal it is not compulsory to both photography and filmmaking and that individual schools will account for teacher capability and student interest.

“This could mean that even if the proposal to expand Photography to include both static and moving image is confirmed, some schools could continue to offer ākonga the opportunity to specialise and deepen their knowledge and skills in photography, but not in film.”

Lost in translation

Lizzy Payne, an art teacher in Christchurch, describes the proposals as “upsetting”.

“If you were a teacher of Painting,” she asks, “and you have 30 kids in front of you and 27 of them wanting to focus on Painting, are you going to start teaching them about ceramics or colour theory?”

Payne compares it to making French, German, and Japanese all one subject, and is concerned the move will discourage students to take Art if they can no longer pursue Painting and Printmaking as separate subjects.

Esther Hansen, Assistant HOD art and Co-ordinator of the Gifted and Talented programme (GATE) at Pukekohe High School expresses concerns over the accuracy of Ministry figures and the lack of consultation with teachers:

“What I am deeply concerned about is the MoE proposed curriculum changes to level 2 and 3 visual art. They want to unbundle the Visual arts from 5 discrete disciplines - Sculpture, Photography, Design Printmaking and Painting down to Photography, Design and "Visual Art". There has been no consultation of teachers up till this point.”

Hansen, who has initiated the petition, points out the Ministry’s figures on students taking Sculpture and Printmaking are only based on one year’s worth of data gathering, whereas many students will take both over two years.

A student, for example, might choose to do level 3 printmaking in year 12 and then go on to do level 3 Painting in year 13. Under the proposed system a student can only do one set of visual art standards and only gain credits in one area.

Hansen also observes a bias towards technology-based subjects. “It is clear,” she says “[the Ministry] think that Design and Photography are more useful than Painting or Print or Sculpture,” noting that this would disadvantage many students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds who share devices with the rest of their family - if they have home access at all.

Hansen also suggests that Māori and Pasifika students find the practical side and aesthetics of Printmaking a resonant cultural fit and tool for exploring social issues. Printmaking as an elective is on the rise in South Auckland schools, and bundling it with other subjects may disadvantage these students.

Hitting the wrong notes

The splitting of Music into Music Creation (theory and composition) and Music Representation (performance, stagecraft, and tikanga) seems a strange decision given that each requires some knowledge of the other.

Music teachers are no less unhappy, reporting that assessment will be reduced to only four criteria, with no group performance, aural, or score reading.

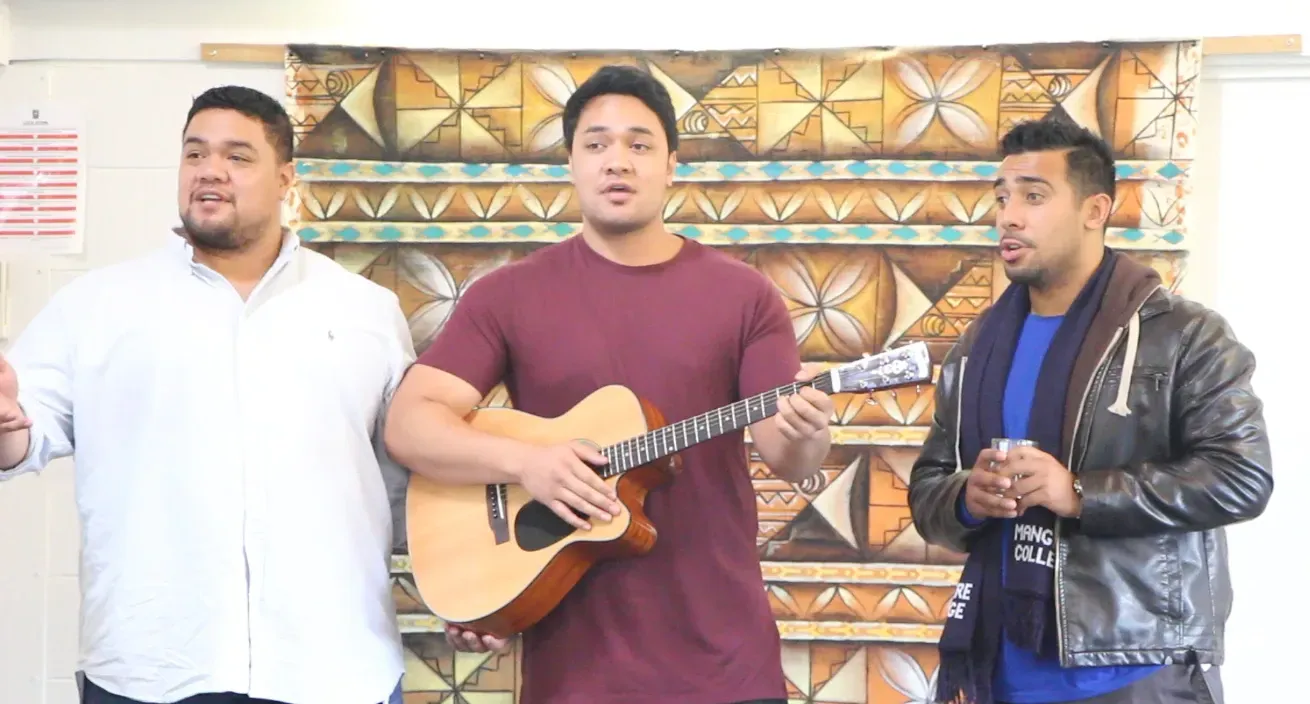

“Take Sol3 Mio,” said Carla*, a South Island music teacher who also wishes to protect her identity. “No way would they be on a world stage without all the classical training they gained during high school.

“If they can’t read a score, develop listening skills through aural training, and learn to perform as groups, then it’s laughable. Those are the hardest things to learn as a musician.”

Internationally acclaimed trio Sol3 Mio perform at Mangere College.

The Ministry responds: “The proposed two subjects for Music at NCEA Levels 2 and 3 are intended to support further opportunities for ākonga to specialise and deepen their music knowledge and skills and provide clear pathways into further study and employment,” and notes that many schools offer Music Studies and Making Music/Performance are offered as separate courses.

“We have taken advice from the Ministry’s Subject Expert Group who believe that expanding offerings in Performance and Composition would be well received.”

Toi Māori

All the teachers spoken to are cautiously enthusiastic about the proposed Māori subjects, but expressed concerns about the practical considerations.

These concerns include whether these subjects would be general electives or for Māori students only, whether there were enough Māori teachers available for a national roll out, the elaborate harvesting tikanga for harakeke, the expense of setting up dedicated carving studios, and whether non-Māori teachers would have a role.

According to the Ministry, these proposed new subjects Mau Rākau, Raranga, and Whakairo, once confirmed and developed, will be available to all schools and kura to offer to their ākonga.

“The proposal to offer these new subjects,” said the Ministry representative, “is part of the Ministry’s commitment to strengthen NCEA through Mana Ōrite mō te mātauranga Māori – recognising a wider range of learning, particularly mātauranga Māori.”

An “appropriate development timeline” to develop resources and workforce, and make final decisions on which subjects to make available to schools and kura has been promised.

“More generally, we continue to support the cultural competency of our teaching workforce; this was a focus of the recent teacher only day through Mana Ōrite mō te mātauranga Māori. We also recognise that attracting skilled professionals into teaching can be enhanced by recognition of their specialist knowledge and skills in the subjects available.”

With the petition to address the collapsing of the visual art subjects closing 9 August and the Ministry of Education call for consulation closing on 13 August - there is time for those who oppose the changes to have their say and to see what their reaction to this backlash will be.

*Names have been changed at the subjects' request.