Using Humour To Tackle Confronting Subjects

Written by

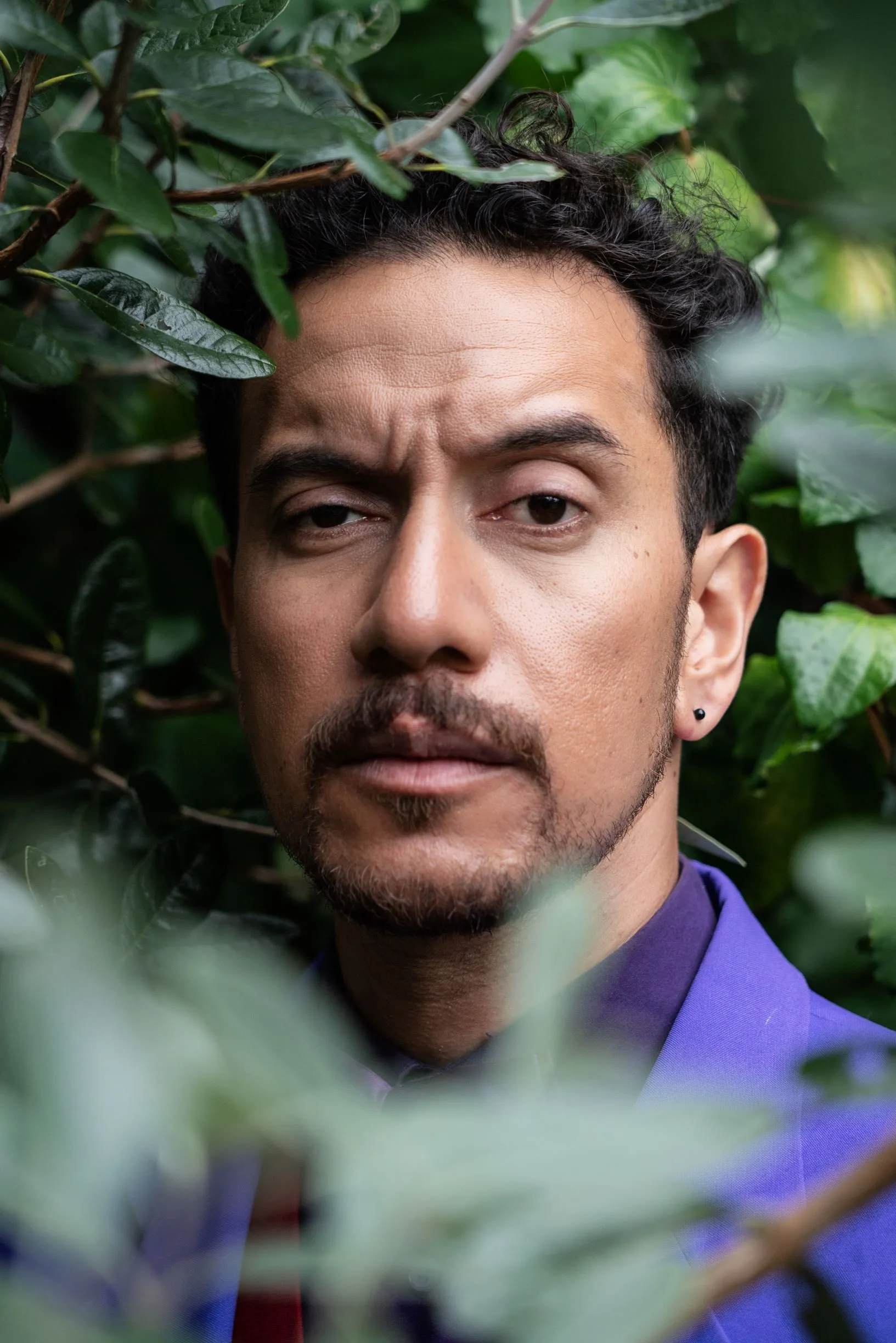

James Nokise knows his way around a joke. The award-winning comedian, podcaster and playwright has brought audiences to life around the globe based in Wellington, Perth and sometimes Edinburgh.

Aside from his Billy T Award nominated live comedy shows, Nokise has garnered a reputation as one of the country’s top podcasters, using honesty and humour to dissect mental health in his popular podcast, Eating Fried Chicken in the Shower.

His latest podcast, Fair Game, has just started on RNZ, using his talents to tackle the challenging topics of equity, race and representation when it comes to Pacific Rugby and how the Pacific nations are treated by World Rugby.

Nokise explains for The Big Idea how comedy can be used to confront the thorniest of issues.

The whole idea that there are subjects that you can’t talk about in comedy is a myth.

Jokes can be made, and are made, about any person or subject. What people don’t always grasp is that laughter is just a joyful consequence. It is not the only consequence there can be to a joke, it is simply the one a comedian is aiming for. Sometimes the consequence is silence, or anger - or worst of all - indifference.

Just because a joke has been told, it does not mean it is funny. It may, in fact, barely be a joke. Because, especially in live work, jokes are never ever finished until they’re performed on stage.

A comic talking about how “edgy” they are and how many taboos they break is usually just trying to establish a brand. No “edgy” comedian worth their salt, that is actually both edgy and funny, has ever referred to themselves as “edgy”. No comic has been “Cancelled” because of their antics on stage.

Everyone is still working. Even the monsters.

Very few jokes don’t offend somebody, somewhere - and just because you and your friends find something hilarious, it doesn't mean someone else doesn’t regard it as modern blasphemy.

A skilled comedian understands who their audience is, and how they will react to their jokes. They know what punchlines will offend certain people, and how, in the same way, other punchlines will get big laughs and which jokes string those sections together.

Knowing that the most professional of comedians have that ability and control, that there is a heightened understanding of the people they perform to, that they are not just chancing their way in and out of scandals on stage… Well that is perhaps what has made the positions of certain international comics difficult for some of their fans over the years.

Humour opens people up, physically and psychologically. It doesn’t just ease anxiety, it also builds trust between a comedian and their audience. But that trust is such an intimate one that a betrayal of it can feel like a betrayal of friendship.

Words are incredibly powerful. When combined with good performance they can both uplift and/or eviscerate the person watching in an instant. It’s what the YouTube story algorithm counts on.

When you’re performing or writing comedy, everything you're doing is to keep the audience's attention.

The currency is time.

Even laughter takes up time, but it also takes energy and an audience's energy is finite. That’s why one of the unwritten rules of stand-up comedy is “don’t run over time”, especially on a line up show, because a crowd can only give so much.

When we say “Comedy is subjective” - what we mean is there is no “best style”, there’s just the style and topics that appeal to you. Same principle as music; classical is not a higher form of playing than electronic, or hip hop, or death metal. Maybe ukulele orchestras, but not in Wellington.

Gallows humour is older than professional comedy. “Bad Taste” jokes are actually important for our sanity. Using humour to cope with trauma is a natural human instinct.

The “N Word” - spoken by the wrong person - can suck the air out of an audience. But the right comic in the right setting can wield it as a tool of empowerment and, funnily enough, community.

Sexual Assault - spoken about by the wrong person - in the wrong setting can silence a crowd. Yet that harrowing subject in the hands of the right comic, in the right setting, can produce a cathartic release for an audience.

Saying “Well who is the right person?” or a variation of “Anyone should be able to say anything?” is not some genius, open-minded, free-speech hot take.

Anyone can say anything. There will be consequences.

James Nokise with SWIDT recording Eating Fried Chicken in the Shower. Photo: Supplied.

When you take an audience into a headspace where they will have to imagine traumatic scenes, the responsibility of their safety is still yours. Sure, they paid for a ticket but that payment is a social contract of trust.

They may expect to be challenged, made uncomfortable, and even angry in some parts - but they also ask two things; make them laugh, and don’t destroy them. That’s why they chose you over the serious show. They want to hear what you have to say but not feel like the world is fucked, they’re to blame, and there’s no way out.

For any comedian feeling like that’s the show they want to do, may I recommend stepping away from comedy, sidestepping theatre, and heading straight over to religion.

There’s been a few comedians, mostly American, who have realised they’re actually meant to be evangelicals. Better pay, better accommodation, and less critique in the green room.

Even the angriest comedians - at their angriest about a subject - aren’t actually preaching. They’re guiding, navigating, using anger to cut through the mental scrub as they lead the audience through a subject.

Anger isn’t always bad - in fact, it can be hilarious. Anger can highlight the absurdity of a situation, the ridiculousness of a story, and bring a crowd together in observing something previously unspoken that’s driving everyone insane.

Photo: Supplied.

The danger is righteously yelling at people can completely shut them down; metaphorically, emotionally, and physically. You get dopemine and the feeling that you’ve won a conflict, but they haven’t really heard you. You’re just the last person talking. You go your seperate ways and nothing changes.

It’s about as useful as a wank, and even those are good for fighting prostate cancer - so actually, less useful than a wank.

Like any other art form, in comedy, you have to be able to answer the question - Why?

Why do you think something is funny? Why is it worth telling a crowd of strangers? Why are you the one telling the joke?

Knowing the answers to those questions won’t just make you a better comic, but probably ease the tension off-stage when someone inevitably hits you up after a show.

An example is when you have an original, brilliant take on a subject, but it’s not going to land as well coming from you. Sure, in a perfect world anyone can say anything, but understanding the world is neither perfect, fair, or that not everyone starts from the same place isn’t even chapter one, it’s the author’s note.

You might be the best comedy writer on the planet, but sometimes you’re not the person who should be taking the joke on stage. Veteran comics know this and so will often write together, or offer jokes to their peers in a green room. The key word is offer - not tell.

If you’re gonna speak on social matters, you cannot be offended when someone challenges why you’re speaking about it. You can be annoyed, and if they’re rude about it, you can be upset. But if you speak on a community, and you have no experience of that community, don’t be surprised when your authority is questioned.

James Nokise’s new podcast Fair Game is available now on RNZ - click here for details.