‘We Cannot Afford to Neglect Them’: STEM the Tide, Save the Humanities

The Big Idea’s recent story on the Ministry of Education’s proposed shakeup to the NCEA Arts curriculum has caused a stir.

Not only is it (at the time of publication) the top-read story on the website, it has prompted a follow-up piece on RNZ on whether the arts are getting downplayed in Aotearoa’s schools in favour of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Maths) subjects.

The prevailing wisdom – from the arts and humanities at any rate – is that economic pressures, the desire for employment stability, neoliberal government policies, rising study costs, and our increasingly technology-dependent civilisation all contribute to a deprioritising of the arts and humanities.

This, in turn, leads to a feedback loop where more and more young people are encouraged to study STEM subjects and away from the humanities, tertiary providers divert resources from the arts to STEM, and this filters down to education policy for schools.

Global trends

To understand this debate, statistics can provide an alarming insight for the arts.

A recent article (paywalled) in The Times’ Higher Education (THE) supplement took a deep dive into the broader issue of whether STEM education is causing a haemorrhaging of the humanities and found the picture to be very complex.

THE reports UNESCO figures showing a dip in STEM among overall degrees in 2012-2014 in the UK and Sweden, but a steady increase since. The US remained stable, and Germany showed a significant rise. South Korea was the only country studied that showed a move away from STEM degrees in that time.

The global trend can only be gauged broadly because different countries categorise subjects in different ways in their data gathering.

The US excludes social sciences from the humanities, for example, whereas Australia includes them with “society and culture” but puts fine arts in their own category.

OECD figures from the THE report, which are more consistent, show Germany and South Korea to have leanings toward heavy engineering and the UK a similar preference for maths and natural science subjects.

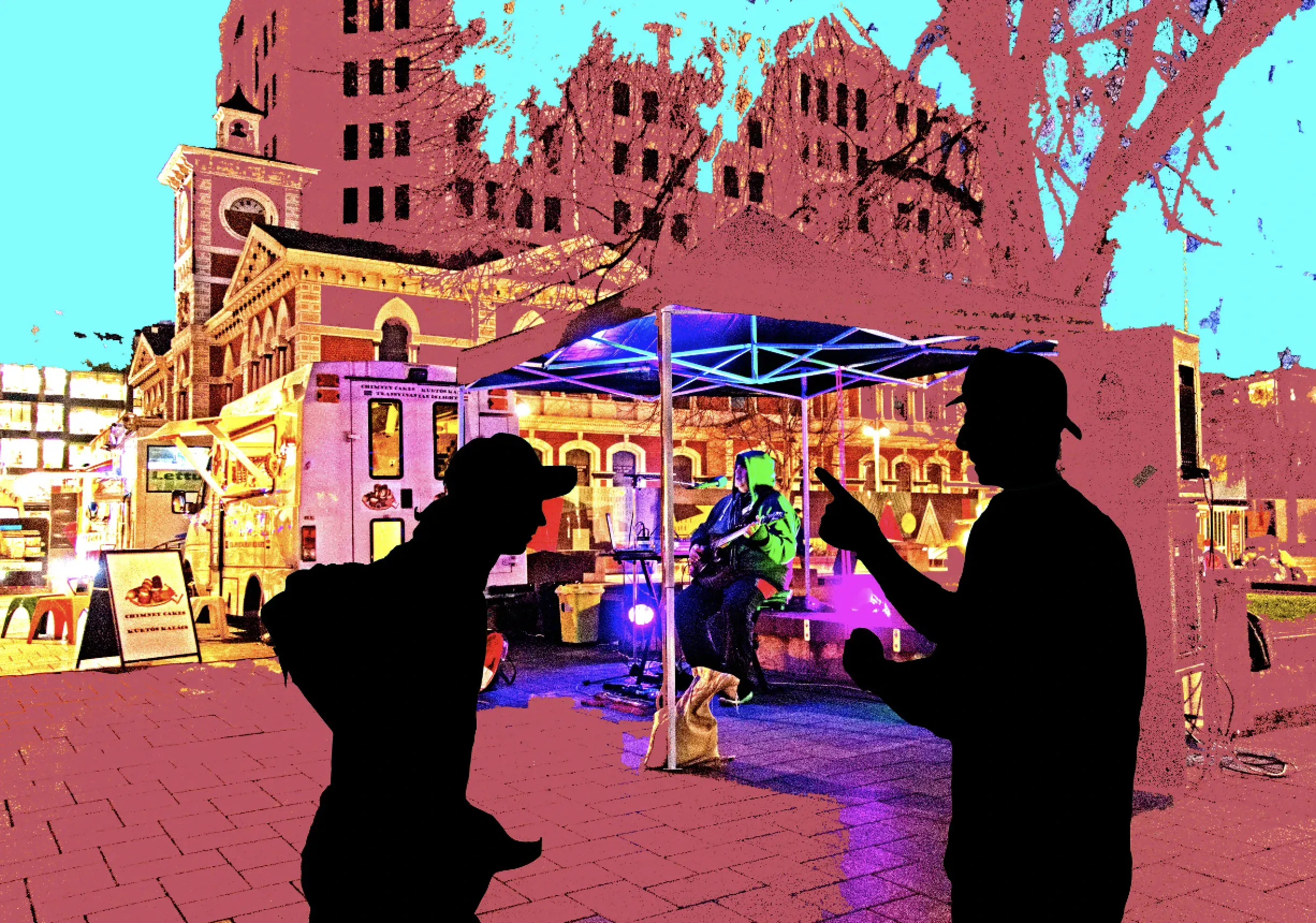

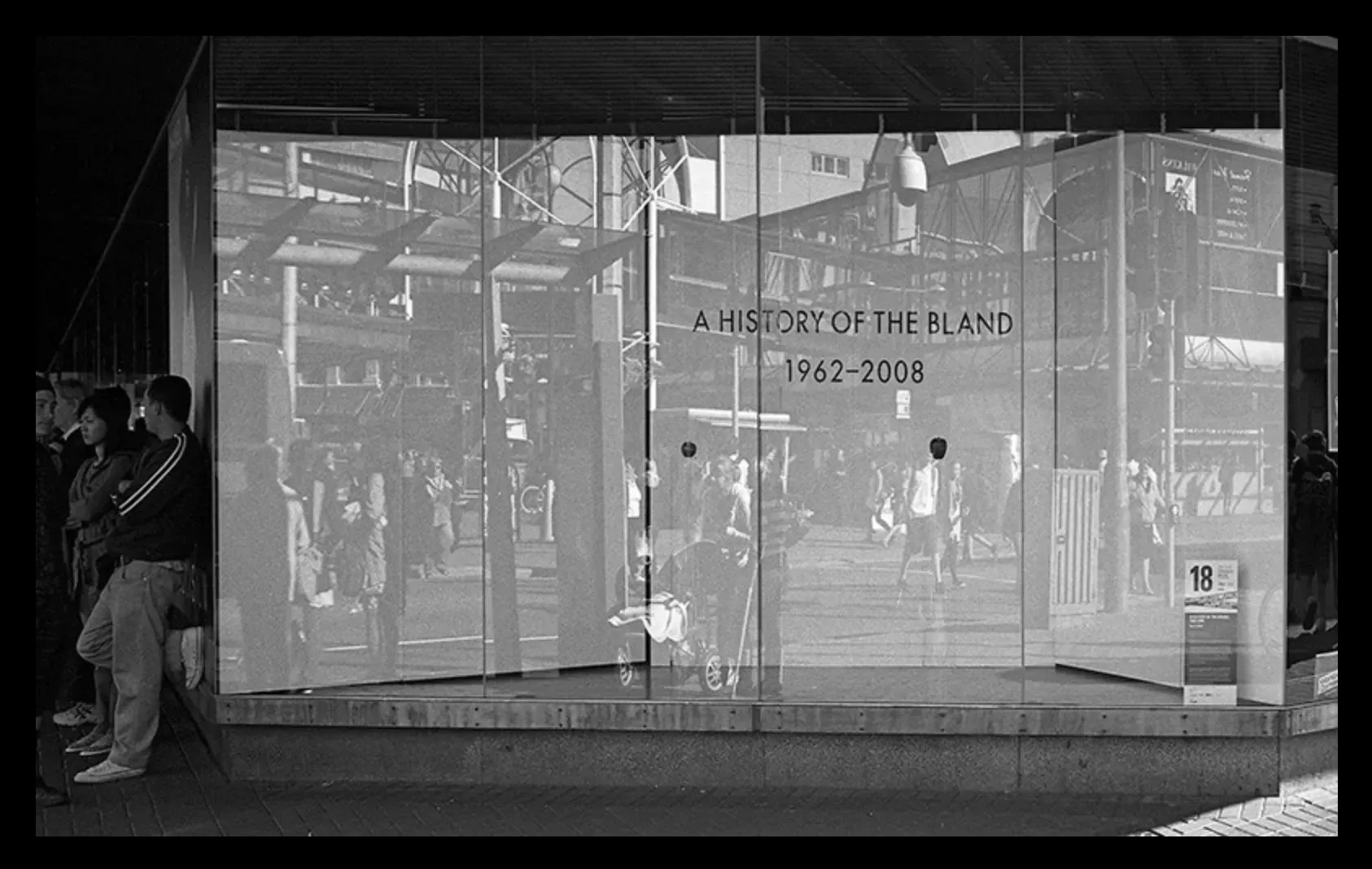

Photo: Doc Ross.

THE also reports that the American Academy of the Arts and Sciences (AAAS) found that in 2009 the humanities counted for 14.6% of all Bachelors’ degrees in the US, down to 10.2% in 2018. This contrasted with engineering growing from 6.6% to 10.3%, and health and medicine from 7.5% to 12.4% in the same period.

From the same article, Germany’s Centre for Higher Education recorded a similar trend, with 36% of tertiary students enrolled in STEM in 2006 rising to 38% in 2019, but humanities dropping dramatically from 20% to 11% in the same period.

It is easy to see why.

A young adult is far more likely to get a secure, high-paying job in a related field with a STEM qualification, whereas it is much more difficult to find an entry position in the humanities, taking much longer to get an equivalent salary.

In many countries, increasing the number of STEM graduates is an explicit policy goal as part of national economic growth.

Homegrown stats

In Aotearoa over a similar period, in Engineering, bachelor’s or higher graduates reached over 2000 in one year for the first time in 2014, an increase of 21% from 2011.

In IT, the number of graduates increased 29% from 2011 to 1550 in 2014. This represented 3.7 per cent of graduates at the bachelors level or higher in 2014.

Natural and physical sciences also increased as a proportion of graduates, reaching 9.4% in 2014, up from 8.9% in 2011. The number of graduates completing a qualification at the bachelor’s level or higher in this field reached 3930 in 2014, an increase of 7.5% from 2011.

Humanities under attack

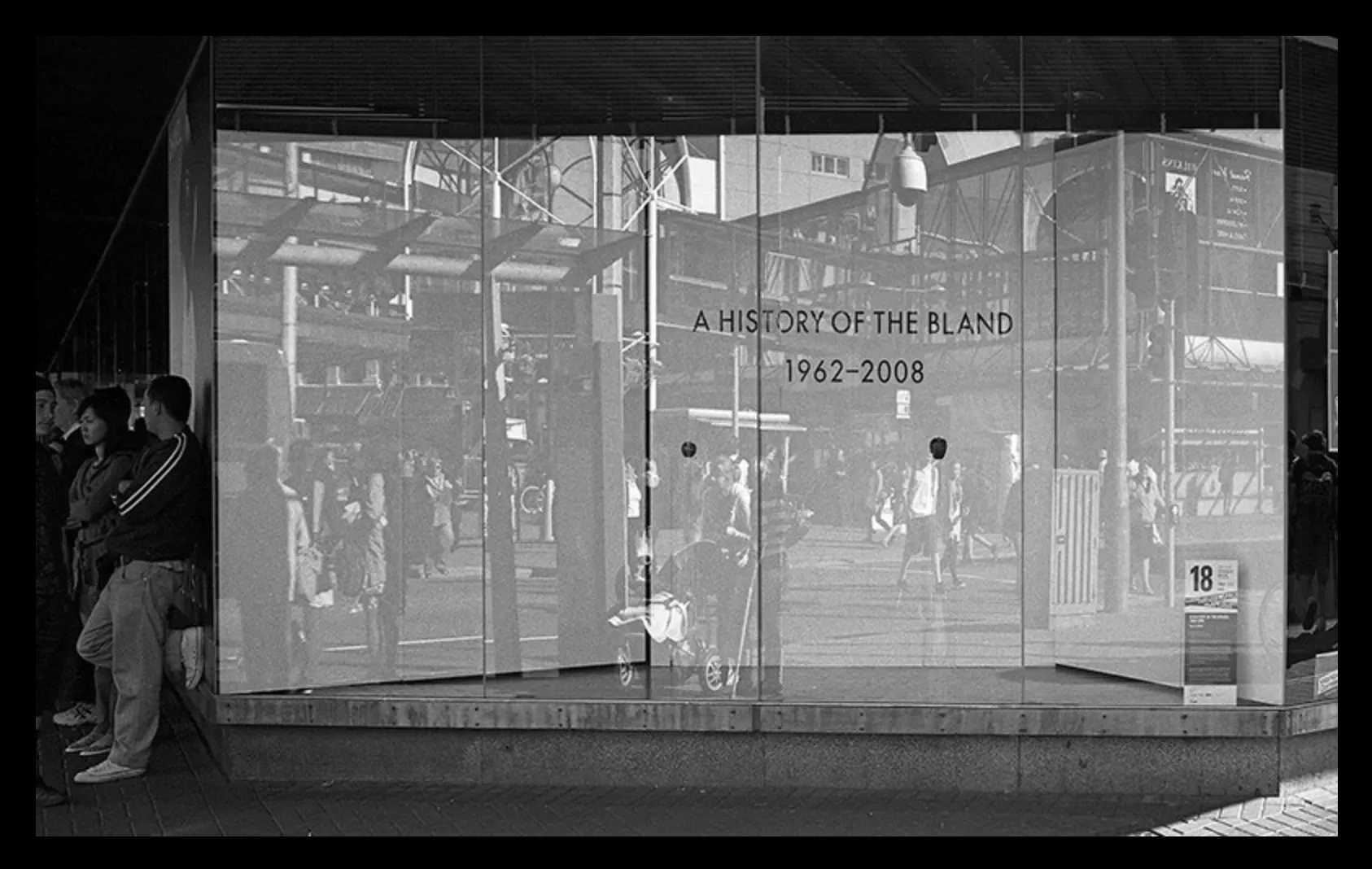

Image: Doc Ross.

In the UK, THE reports, the Longitudinal Education Outcomes (LEO) initiative has allowed British politicians to cross-reference the tax records of graduates with degree types in pushing more school leavers towards STEM studies and attacking humanities subjects as “low quality”.

In Germany, with its tech and manufacturing-based economy, this would make sense. In the UK the impetus is less clear as it’s a predominantly service economy, though maybe that is just politicians latching on to the term “knowledge economy” with only a very narrow interpretation of “knowledge”.

That said, the UK deeply values its cultural heritage and there is no evidence that funding for the humanities is declining there.

Closer to home, the Australian Government is putting out a similar line about STEM subjects, employability, and “job-ready graduates”. The Australian Academy of the Humanities noted a peak in overall tertiary enrolments just before the COVID-19 outbreak, but of those, humanities enrolments had dropped from 29% to 26%.

According to Kylie Brass, Director of Policy and Research at the AAH, this push by Canberra assumes that STEM means employability, which isn’t backed by the evidence and “sends the wrong signals to universities about employability, industry needs, and the future of work”, reports THE.

Fee increases at Australian universities also have a flow-on effect in Aotearoa, discouraging New Zealanders from studying there and furthering a negative view of humanities education on both sides of the Tasman.

STEM on our shores

It’s less clear how these trends translate to New Zealand where the economy is driven by the export of primary resources, GDP is far smaller, and cultural values skew differently. The New Zealand Government has identified STEM as critical for the country’s future.

In May, the Government announced a $3m boost to STEM education, and the Ministry of Education is heavily promoting STEM education to Māori with reference to Mātauranga Māori, and creating scholarships for women in STEM fields.

The New Zealand media can also be inclined to provoke parental panic by highlighting the decline of maths and science skills among school-age New Zealanders in relation to other countries, stoking the fires of cultural cringe.

New Zealand has its own prejudices about culture. Never has a career in the humanities looked less appealing. Creative New Zealand (CNZ) and New Zealand on Air (NZOA)’s 2019 study of creative professionals revealed that their median annual income was $35,800 compared to the $51,800 national average.

That number drops to $15,000 when other income sources are subtracted. One might wonder how that compares to the salaries of CNZ and NZOA management. Stuff crunched the numbers of CNZ’s response, a revised remuneration policy, and found even that sadly lacking.

Then there is the tertiary sector.

The dependence of Aotearoa’s universities on international students is potentially a major factor as they predominantly enroll in STEM subjects irrespective of domestic demand, although COVID has put a significant dent in this.

Even assuming a full post-COVID recovery in the midterm future, STEM research is also far more likely to attract funding and kudos to New Zealand universities and thus receive preferential attention.

The battle ahead

Art imitating life? Photo: Doc Ross.

More generally the concerns are that the humanities are increasingly seen as elitist or out of touch, for the privileged who can afford “hobby” subjects, useless, impractical, Eurocentric, or overly politicised.

In a 2021 opinion piece in Stuff Nick Agar, a Professor of Ethics at Victoria University of Wellington, brazenly erupted in STEM boosterism, condemning the current state of humanities education as being “buried in the past”.

Recently we also saw seven University of Auckland academics writing a letter to the NZ Listener outraged at the proposal that Mātauranga Māori be taught on par with western science. This sort of thing doesn’t help allay public prejudices.

COVID has had a massive impact on the precariat of the arts and culture sector. As Graeme Turner, Emeritus Professor of the University of Queensland’s Institute for the Advanced Study of the Humanities told THE, the latest figures don’t reflect the actual impact of the pandemic on an increasingly casualised humanities workforce.

“…the prospect of employment for early-career humanities graduates is currently very poor,” says Turner, warning that in the present climate, it is very easy to characterise the humanities as, “the most privileged and least useful of the things that universities do.”

If a general foundation of humanities education can be maintained in our universities, they can always spring back if demand increases, but not if governments send out mixed messages to tertiary institutions and school leavers.

Humanities departments continue to be shuffled around, amalgamated or shuttered, and the slashing of academic humanities positions at a time when we need critical thinkers more than ever.

Of course, in saying that we clearly need to move beyond the usual defence of the humanities as a common good in of itself. There are a plethora of benefits from a humanities education, including an increased likelihood of employment and higher wages in general and associated soft skills.

The liberal arts bring important problem-solving skills to business education, and have long-term implications for health and wellbeing. We might struggle to afford them, especially in a COVID economy, but we cannot afford to neglect them either.