Could On Set Shooting Tragedy Happen in NZ?

Screen workers are experiencing collective grief and asking questions about industry safety in the wake of a tragedy that has gripped the international film community.

In a small, makeshift church on the set of Rust in Santa Fe, New Mexico, prominent actor Alec Baldwin was practising pointing his firearm towards the camera, when it discharged - killing director of photography, Halyna Hutchins, and injuring director, Joel Souza. The New York Times reported that the First Assistant Director handed Baldwin the weapon, and said, “Cold gun”.

New Zealand might be half a world away, but in an industry whose life force depends on its global connectedness, the tragedy felt close to home.

Stats NZ shows the screen industry employs over 16,000 people, and has a gross annual revenue of around $3.3 billion, and is mostly funded offshore (although COVID will have made a dent). The new Film Commission Chief Executive, David Strong, says in an excellent interview on RNZ that international film productions coming into New Zealand bring in about $600 to $900 million annually.

How it works here

The Big Idea has spoken with an experienced armourer (under the proviso of anonymity) who feels a sense of shock and disbelief at the tragic events in Santa Fe, and at the stark absence of safety protocols.

The accident couldn’t happen in New Zealand, he says. “It is illegal to have live, complete ammunition on set”.

On our shores, (modified) firearms on set can only be fired under the “direct, close supervision” of an armourer, with blank ammunition as the conditions of the police endorsement for broadcaster/ theatrical purposes. Armourers provide plans for the health and safety of cast and crew, and safe transport and on-site storage of weapons.

New Zealand armourers have strong on-set protocols for the use of firearms.

The armourer we spoke to says there are still important lessons to be learnt. “Alarm bells” went off for him around having a young, inexperienced armourer in a high-risk situation.

Risks happen around film productions when people are trying to take “short-cuts” to keep production length and cost down. He says, “you have big egos” working on film sets, so “to a certain extent, it becomes a cultural problem.”

You need to be able to say no to people.

His viewpoint is echoed by Brendon Durey, who works as a special effects supervisor on-screen, and is the Managing Director of Filmfx, a company that provides special effects to film and tv productions, which includes an armoury. Durey was the special effects supervisor on a recent episode of Netflix Sweet Tooth (2021) and movie Guns Akimbo (2019).

He points out that the safety process for an armourer to hand a firearm to an actor on set is a four-person checking process. The armourer checks that the firearm is unloaded; the safety officer checks it; the Assistant Director checks it again; then it is handed to the performer who also checks that it is clear.

Brendon Durey. Photo: Supplied.

Screensafe have developed guidelines for the firing of blanks based on identifying “exclusion zones” where crew cannot be placed because of the potential for injury. Durey says these protocols for armourers on film sets are “fairly universal around the world”.

He points out that film sets have many comparable risks, such as pyrotechnics, where the risk is managed by a principle of keeping crew out of dangerous areas.

Why use real firearms?

While there are calls for the complete banning of firearms on set, Durey says the cost of solely using fake firearms is prohibitive for film productions. A bespoke fake firearm will cost you around $6500 to $7000 dollars, “when the actual real gun that you are moulding is worth $400.”

He says it’s a case of supply and demand where the production costs of making a bespoke prop can’t compete with the low cost of firearms.

Durey says, “You look at say, the AK-47 - there’s 50 million of them in the world, there are not that many fake ones. A real AK-47, you can buy for $200 in Europe. Even a cheap fake one, you are paying four times that.

“It quickly becomes, ‘let’s just get a license and have the real ones because it is cheaper and easier, and they look better’.”

Real guns are often used for close-ups on set because of the level of visual detail required, particularly to show the character cocking or reloading the firearm. When possible, the firearm is modified by screwing into the barrel and putting a thread through so that it can be “choked” to stop it firing.

But news reports about the Rust set that revealed guns were used for target practice confounded him. “That there was live ammo on set baffled me and a lot of people. We don’t even have live ammo at our workshop,” he states, “there’s just no place for it.”

I asked Durey what the challenges were for keeping film sets safe.

Durey replies “you have to have someone experienced, that can say no to people”. To the bored people that don’t think they should repeat safety protocols or sometimes directors will want the gun pointed at people, and the armourer will have to refuse. Durey says “you’ll get directors that will throw a tantrum if he doesn’t get what he wants”.

One of their challenges is getting the cast and crew to understand that you can never point a prop gun at anyone - whether it is real or fake. That’s right - you can’t even point fake guns.

Once, an art director pointed a rubber shotgun at a camera operator as a joke. Durey emailed his supervisor saying, “This is your final warning, this cannot happen again.” The reason is that high-quality fake guns look the same as real ones, and people can’t tell the difference. “We don’t want anyone to get into the habit of joking around and thinking it’s okay to point one of these at someone else.”

Sometimes FilmFx armourers will simply refuse to hand a gun to someone. “You have to take it really seriously.”

More important than money

I ask how their armourers deal with conflict on set or non-compliance. Durey explains that he lets his armourers know that if they are on set and “the director or someone is acting a bit reckless, and they start pushing back hard...you’ve got every authority from me to put the firearms in the truck and lock them up.”

Durey says safety needs to be the priority on set, “and if we lose the contract, or the producer is running after me angry, just know I am behind that (armourer) 110%. I would rather not do a contract with someone who is going to put us in that position and I’m happy to walk away from it. Some things are more important than egos and money.”

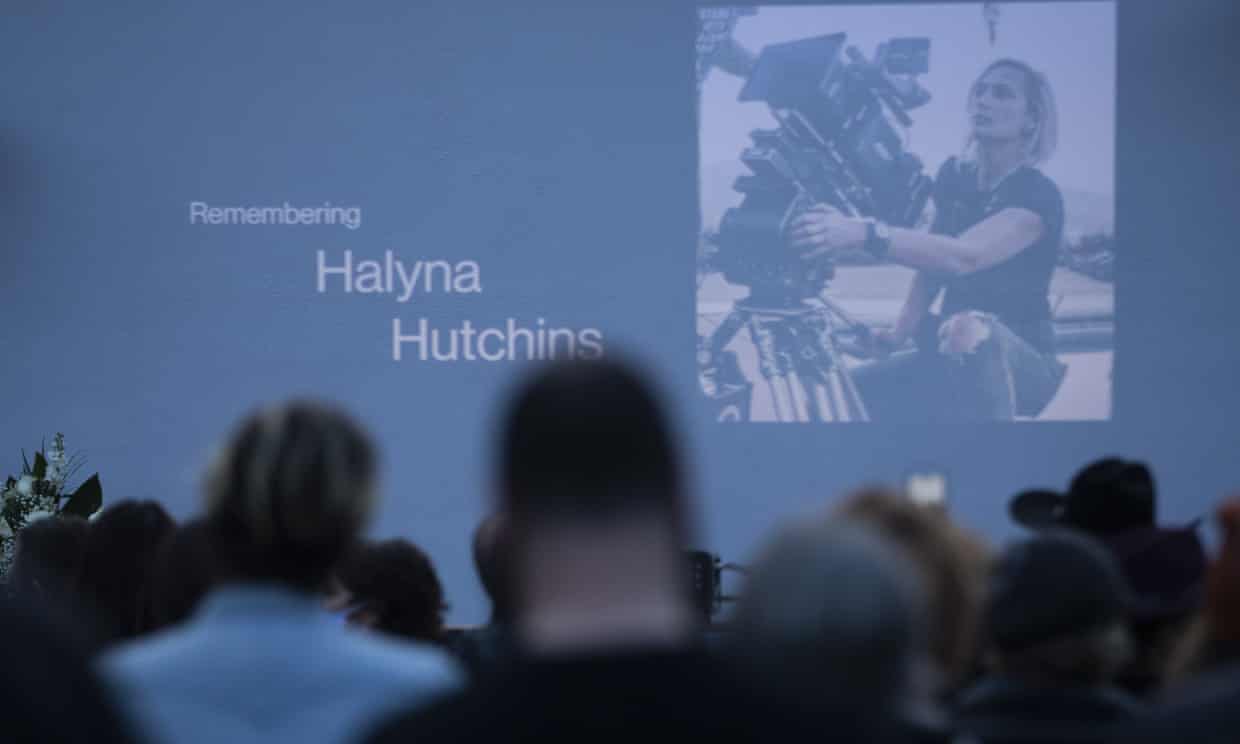

A candlelight vigil is held for Halyna Hutchins in Burbank, California. Photo: Myung J Chun/Los Angeles Times/Rex/Shutterstock.

The Guardian reports "several hundred colleagues" attended a vigil for Hutchins outside the local union office of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE), where U.S. based crew have described long hours and poor work conditions. It’s also reported U.S. cinematographer Antonio Cisneros believed Hutchins’ death reflected deteriorating work conditions as a result of digital streaming platforms forcing leaner productions on tight timelines.

Could our collective hunger for Netflix and Amazon binge-watching create less safety here?

Production under pressure

Matthew Metcalfe (left) with director Toa Fraser. Photo: Supplied.

I was curious, too, about whether New Zealand-based producers and directors push back against safety protocols. Producers are responsible for getting the film made, on time and within budget. Directors are responsible for the overall creative vision. How much do the pressures of getting a film made conflict with safety?

Film producer, Matthew Metcalfe, talked about his experience of producing 6 Days - an action thriller directed by Toa Fraser - based on a real-life siege at the Iranian Embassy in London in 1980 when six armed gunmen held 26 people hostage.

6 Days is an unusual action film in that it feels journalistic - characters are closely observed, but not judged. There’s a vivid realism to 1980s London where SAS officers load and carry Heckler and Koch MP5 submachine guns.

Jamie Bell and cast with MP5’s in 6 Days. Photo: General Film Corporation Limited.

Given the number of firearms, I asked Metcalfe what he was thinking about while it was in production.

“It begins and ends with safety. I was thinking of the welfare of the cast and crew, and that is done by doing it by the book, and constantly managing the need to check, cross-check, double-check and check again.”

Metcalfe’s disciplined approach to safety might be influenced by years spent in the army in Australia and New Zealand. His recent productions include We need to talk about A.I., Mothers of the Revolution, and Dawn Raid.

Metcalfe explains that as a producer, ensuring that firearm use on sets is safe starts with the hiring decision to employ a professional and qualified armourer: “It's zero tolerance for anything other than the highest level of professionalism, with the strictest protocols, and to empower them to do their best work.”

Producers need to establish an on-set environment of checking that safety protocols have been followed, “you run safe protocols and check it and recheck it”.

Metcalfe reaffirms that there is no place for live (complete) ammunition on set. “It is beyond unimaginable in a New Zealand context,” he says, “and it is unacceptable.”

Be an "arsehole"

Renowned actor and director Ian Mune OBE, has responded to the Rust tragedy by writing a compelling public post on Facebook, demanding that the film industry take firearm safety seriously.

Ian Mune. Photo: Supplied.

Mune is currently on screens in TVNZ’s The Pact, and is well regarded for his extensive acting, writing and directing career, including directing The End of the Golden Weather and Came a Hot Friday.

In his Facebook post, he says as an actor, he knows actors are distracted by characterisation and line-learning - and are therefore unfit for being solely responsible for firearm safety. Instead, he says professional armourers are essential and that they need to be an “arsehole” not intimidated by “star power or producer shit.”

When The Big Idea spoke to him on the phone, Mune’s resonant voice was thoughtful. He was adamant that a director’s vision should not override the safety of the set.

“As a director, you listen to what needs to be done [from an armourer] and you listen and adjust. There are 101 ways to shoot everything.”

Mune had first-hand experience of firearm risk, when he was directing a play and he was burnt by the wadding of a discharged blank, fired from 10 feet away from him.

I asked Mune whether the tragedy in Santa Fe would make him reluctant to act in scenes with firearms. “No, not for a moment,” he said, “providing there was an experienced armourer and protocols were being followed.”

He paused.

“But if protocols weren’t being followed, I would walk off the set.”