What Has Changed After Aotearoa Music's #MeToo Moment?

Ten years ago, Singer-Songwriter Lydia Cole burst into our musical consciousness with her sweet, introspective lyrics and melancholic songs in the album Me & Moon. She is a two-time Silver Scrolls finalist for the songs Hibernate (2012) and Dream (2015). Her last solo album, Lay of the Land (2017) was critically acclaimed.

She has also stood tall in another way.

In January last year, Cole spoke bravely about the abuse of power by manager Paul McKessar from CRS, who inappropriately initiated sexual relations with her while she was a young musician. Cole was joined by Lead Singer Possum Plows, with whom McKessar had an inappropriate and exploitative relationship. Manager Scott McLachlan of Warner Music admitted sexually harassing multiple women as Stuff blew the lid off the long-simmering story.

At the time, singer Tami Neilson spoke on Instagram about the ‘deafening silence’ of the music industry.

One year on, Cole says there still needs to be transparency and genuine change from those accountable.

“I want to hear about transformation in people who were previously causing harm, enabling destructive behaviours or turning a blind eye. I want to hear in their own words what they understand now that they didn't understand before.”

In this article, The Big Idea asks how the music industry has responded to the necessity for change.

We were interested about the responses of women and non-binary people in the industry. We wanted to hear from industry bodies about initiatives on the ground. And we wanted to know whether music management companies like CRS had responded to those who spoke out.

Have they changed how they treat women and non-binary artists?

Abuse of power

An anonymous Instagram account Beneath The Glass Ceiling NZ (BTGCNZ) has been calling out the bad behaviour of men in the music industry for the past 12 months. It posts anonymous accounts by people who have experiences of sexual harassment, sexual abuse, abuse of power and bullying within the music industry - removing any identifying features. At the time of publication, It has 15.7K followers.

It is harrowing, but necessary reading. As I read through the 70+ posts, some recurring themes occurred. A heart-breaking aspect is that many of the women were not supported when they raised the issue with others in the industry.

So often in the accounts on BTGCNZ, the perpetrating man was in a position of power - an executive at a major record label, a prominent festival promoter, even performers from well-known bands.

“Power imbalance is the most important cause of workplace harassment,” agrees Dr Jeff Crabtree, from the University of Technology, Sydney. Crabtree is an accomplished Australian songwriter turned academic, who wrote his doctoral thesis about workplace and sexual harassment in the Australian and New Zealand Music industry.

His survey of 154 people, found 84% experienced some form of harassment, while 18% of women regularly experienced humiliation and ridicule, and 7% of women experienced sexual pressure on a daily or weekly basis.

I asked Dr. Crabtree what are the drivers of sexual harassment in the music industry. He explains, “Misogyny is endemic in the music industry”. Misogyny is a worldview by people who think of women as less equal, or less capable or “less suited to certain roles than men.”

Crabtree gives the example of sound engineers who don’t think women performers can adjust their own microphones or amplifiers.

In 2019, the Amplify Aotearoa report by APRA AMCOS found 70% of women experience bias, and 45% of women reported not feeling safe where music is performed or made. Specific types of work within the industry are extremely gendered: 85% of audio engineers are men and 77.9% of producers are men.

Misogyny ‘gives permission’ for men to sexually objectify women. Crabtree explains, “They feel able to treat a woman as though her value is only in her appearance or what she offers them sexually.”

Perpetrators in the industry are able to abuse women precisely because their influential positions make it difficult for women to turn them down or expose them.

Crabtree details “the power that's been exercised is the power of gatekeeping. It's the power that is exerted inside a social or cultural network, where the gatekeeper has the power to give access to something that's valuable.”

So in the case of record labels, it's who can give access to a record deal. In the case of a manager, it's who can give access to the record labels, or who can access the connections.

Crabtree says, “How do you bring that person to account if they can end your career?”

Some industry fall-out from BTGNZ has already been experienced by Shelley Te Haara (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Rangi), a music industry behind-the-scenes multi-hyphenate, Te Haara has recently been subjected to a legal threat from an anonymous man - “Mr X” - within the industry, afraid of the reputational damage the BTGCNZ might cause him - even though it is entirely anonymous. And BTGCNZ has explained that - despite Mr X’s lawyer’s belief - Te Haara is not the person responsible for the Instragram account (See David Farrier’s webworm about it).

Shelley Te Haara. Photo: Supplied.

Reflecting on both BTGCNZ and artists who have spoken out, Te Haara says ‘people don't want to be quiet about things anymore. I think people are just over being treated differently and pretending to be something they’re not.’

Te Haara does photography and videography, PR, music management, and even merch and security. They enjoy the excitement that comes with working in the music industry. It has been a learning curve, but “getting back to being my true self and enjoying what I do again - the right people and opportunities just gravitate towards you.”

Te Haara has already shown rebelliousness and smarts when it comes to improving the industry for women and non-binary people. Neck of the Woods wrote that in 2020, Te Haara and their twin Maz was actually behind a cool spreadsheet for women and non-binary people to list their acts for promoters. They were frustrated by the lack of action by promoters who wrongly claimed their lack of gender equity in festival line-ups was because there weren’t enough women and non-binary performers.

Te Haara tells artists to remember that the industry doesn’t exist without them.

Sarin Moddle, who works in tour management, production and site coordination, says the Amplify Aotearoa report was a “pivotal spark” for getting traction about gender in the music industry alongside BTGCNZ.

“Those two things, have really prompted a conversation that was not happening prior to that,” she pauses to reflect, “rather the conversation was happening, but it was only happening basically between women, we all acknowledged that it was happening - but men were not really a part of that conversation.”

Sarin says a risk factor is that the industry has very few permanent, full-time positions. In the live industry, most people are independent contractors who depend on the relationships they build within the industry for work.

She told The Big Idea: “I also have found myself in situations where I have recognized that it will be beneficial to me, for someone to like me. So I will laugh at all their jokes, and I don't think they're funny. I'll come out for drinks. But no, I would rather just go to my hotel room and get my work done.”

Moddle says the industry has a problem with gatekeepers.

“The majority of the decision-makers in the live industry are still overwhelmingly male. Adding the older man/younger woman dynamics onto an already existing power dynamic of the scarcity of paid roles in the industry can lead to easy exploitation of those layered power dynamics.”

Sarin Moddle: Photo: Supplied.

Across hiring by production companies in the Live Industry, Moddle says the excuse would be “we would hire a woman but we just can't find any”. While Moddle recognises there is a real shortage of women in live roles, she says businesses needed to take responsibility for creating training and upskilling opportunities for women and non-binary folks, “to strengthen that talent pipeline.”

In April, Covid allowing, Moddle will be touring with Crowded House in Australia, where the band has partnered with an organisation for young people in music, The Push to offer two internship roles in stage teaching and tour management for women and non-binary folks to gain tour experience, “In addition to making a conscious effort to hire in a more diverse manner, That’s the kind of stuff that needs to be happening”.

Music manager Verena Mornhinweg, who has managed Psychedelic Rock Band Makeshift Parachutes, points out that women are still outnumbered on festival lineups, representation on radio, and coverage in the media.

Mornhinweg, 32, who migrated to New Zealand from Germany when she was 21, has had positive experiences within the New Zealand music industry, “I felt accepted and supported.” But the situation is complex, “women are presented in the media as more sexualised or objectified.”

Mornhinweg DJ’s House music as DJ Verenity, has worked as an assistant to Andrew Spraggon from Sola Rosa, and currently works as a radio presenter at a local community radio station RTRFM 92.1 in Perth.

Mornhinweg emphasised that making small changes across the sector is necessary for challenging inequality. She says: “small incremental change from the bottom will hopefully change the big picture.”

As a radio presenter, she gives women and non-binary artists as much air time as men.

Music industry bodies respond

Teresa Patterson. Photo: Supplied.

The Chair of the Music Management Forum, Teresa Patterson says that despite increased awareness and accountability, “there is still a long way to go.”

MMF is an independent, not-for-profit collective voice for music managers and self-managed artists. Patterson says that fairness and safety for women in the industry has always been a priority. They introduced a Code of Conduct in 2015, and last year implemented a Code of Conduct for anyone associated with MMF. Their eight-person Executive team has five women and 5 BIPOC.

Patterson has over 25 years of experience working as a music manager and promoter. She is on the board of the music charity MusicHelps, and along with musicians Julia Deans and Lani Purkis, created the female/non-binary focussed music festival Milk & Honey.

Patterson told The Big Idea “we need more women in (company) management positions, more women on boards, more women music managers, more women on festival lineups, more women crew. And all workspaces need to be safe spaces.”

Addressing sexual harassment and creating safe workplaces requires organisational changes, Patterson states that “proper change comes from the top, therefore the industry needs the men who hold positions of power to do what they can to help create actual meaningful change.”

Soundcheck Aotearoa is an action group of music professionals formed in 2020 to create a more inclusive industry culture and address inequitable representation. Jo Oliver, spokesperson for Soundcheck, says, “we believe that everyone is entitled to be safe at work.”

Following the early 2021 revelations, Soundcheck commissioned a report about how to create changes in the music industry called “Creating Culture Change around Sexual Harm in the Music Community in Aotearoa”.

The report, released July 2021, looked at how to prevent sexual harm in the industry, and how to respond to it occurring. Workshops in Auckland and Wellington canvassed 145 industry workers, and the themes that emerged included ‘The Boys Club’ and sexist industry norms, as well as insecurity of income making it easier for power to be abused. Substance use and the small size of the industry were also contributing factors.

Recommendations included embedding an industry standard Code of Conduct, training, and improving response systems to sexual harm.

Jo Oliver. Photo: Supplied.

I asked Oliver about what happens at Soundcheck Aotearoa’s Professional Respect Training. She explains that Professional Respect Training is a free interactive training day for the music community, delivered by experts in sexual harm prevention. The training includes how to support someone who has experienced harm, options for reporting and support, and prevention strategies.

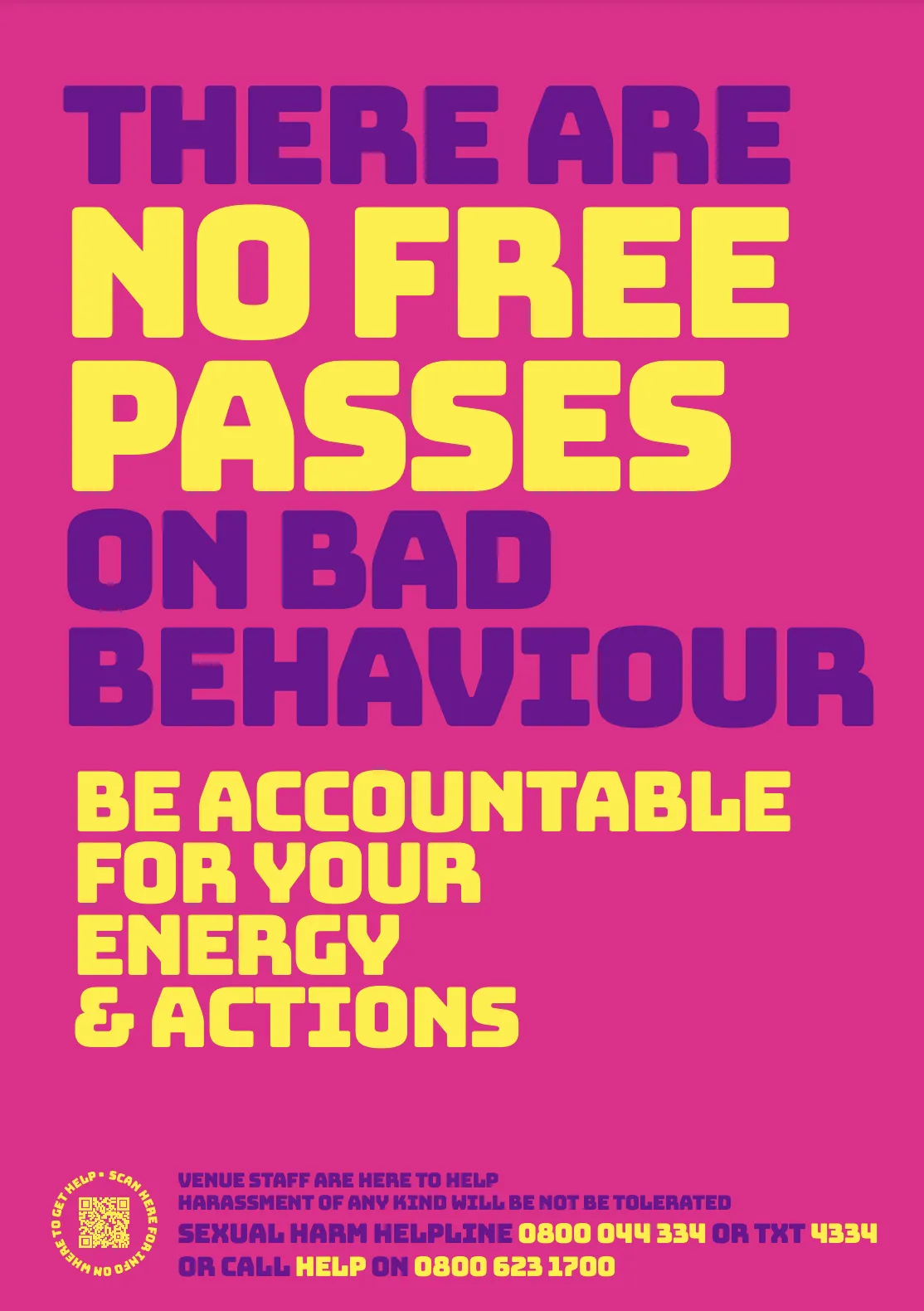

Oliver says “we encourage participants to help with culture change by doing some prevention in their everyday work, like adopting a workplace policy or using posters at a gig.”

More than that, it’s about creating culture change about sexual harassment. “More than the specific content, the training day supports people to talk openly about the issue and see that they can all play a part in preventing sexual harassment.”

Unfortunately, Omicron has meant that the workshops haven’t been running. People who are interested can be added to their mailing list for updates.

I asked Oliver whether in a scenario where a music manager had abused his power and been fired, what kind of actions would she like to see from music management companies?

One of the resources available at Soundcheck Aotearoa.

Oliver says every situation is different and a range of measures may be appropriate depending on the wishes of the survivor, the risks factors at play in the business, and what processes are in place to manage the risk of sexual harassment.

“We encourage everyone in the music industry, whether a sole trader or larger employer, to consider what they can do to create a culture where sexual harassment is not tolerated and there is accountability.”

Soundcheck developed a flowchart to support businesses to respond well to reports of sexual harassment. What feels clear is that by creating a respectful work environment and clear policies, you can help prevent sexual harassment from happening.

What role does Government play?

I asked Dr. Crabtree what he thought needed to be done.

He pointed out that we already have existing legislation for both workplace and sexual harassment, but it doesn’t prevent harrassment from happening. “It rests with governments giving thought to how legislation can be best enforced in a laissez-faire environment like the music industry.”

Dr. Jeff Crabtree. Photo: Supplied.

Crabtree says music funding should be linked to workspace safety, “Government funding for music projects needs to be connected to and contingent upon really well-enforced workplace harassment and sexual harassment policies,” He says, “I'm talking about zero tolerance, which means you need to have your funding taken away from you if there's an incident where you are deficient.”

I asked Head of Music/Tumuaki o Te Puoro at NZ On Air/Irirangi Te Motu David Ridler whether NZ On Air made funding conditional on safe workplace practises.

Ridler replied “I can confirm NZ On Air does include Health & Safety clauses in all of our funding agreements with artists/rights holders for each Single or Project grant.”

He explained that in 2020, NZ On Air introduced a Safe Spaces Agreement as a separate schedule in the New Music Development agreements (where newer artists work with established music producers) “that requires both the artist and producer to sign.”

Since then NZ on Air have been expanding the inclusion of Safe Spaces agreements across all our music funding contracts. Ridler elaborates “these agreements specifically address discrimination, harassment, abuse, professional respect, physical boundaries and a number of other areas of potential harm or unsafe working practices where there may be issues of power imbalance or other issues.”

NZ On Air was part of the initial working group for SoundCheck Aotearoa and to date they have invested $80,000 towards it. NZ On Air also monitor and report on gender diversity among funded singles, projects and artists. They are relaunching their diversity reporting later this year with a wider scope.

NZ On Air are currently approving a higher percentage of applications from female and non-binary artists relative to application numbers from those groups. Ridler says “we’re really conscious of the need to ensure female and non-binary artists feel able to participate.”

What still needs to change?

Verena Mornhinweg. Photo: Supplied.

Mornhigweg points out that audiences also can play a part in creating change, saying, “make sure to listen and buy songs of female artists, so their songs get plays and they get booked for festivals.”

Te Haara says despite the changes brought about by #Metoo and BTGCNZ, “so much” still needs to change. They say that labels, radio and companies need to “do the work internally” instead of waiting to be called out to make changes. They have been astounded at the people who “protect their image”.

Te Haara says “People need to stop trying to silence those coming forward and don't punish those who have because it may affect your image. Just do the work and do better.”

Dr. Crabtree points out the massive impact of sexual harrassment on women in music.

“What happens when we lose the voice of a songwriter, an artist, because they've had to leave the industry due to their experiences of harassment being so traumatic that they can't continue? That’s an enormous loss. What an enormous loss to a culture. It's not quantifiable.” He pauses, “I think it's devastating.”

He says that change requires real commitment from people in senior leadership. “There has to be zero tolerance, which means whenever it occurs, you have to act swiftly to stamp it out”.

This was echoed by Patterson from MMF who says organisational change needed to come from men in power.

“Unfortunately there is still a lot of talking the talk, but faking the walk”.

Just do better

As I worked on this story, I couldn’t help feeling the brunt of the work of creating change was falling to women and non-binary folk, and not by men in positions of power.

CRS Music Management Limited was run jointly by two men, Paul McKessar and Campbell Smith. McKessar joined CRS in 2004. The Companies Office shows McKessar ceased as director on 27th January 2021.

Six months later, in July 2021 when CRS filed their most recent annual report, Fallen Piano Ltd was still a 50% shareholder. Fallen Piano Ltd is a company owned jointly by McKessar and his wife Fiona McDonald (50% shareholdings). That would seem to suggest that despite being fired and resigning as director, McKessar is still effectively an owner of CRS through his company Fallen Piano Ltd.

Stuff reported last year at the time of the disclosures, Campbell Smith posted on Instagram saying the company had not met standards “to provide a safe environment to our clients”. Despite this, Smith still accepted a New Years Honour in January 2022, for services to the music industry.

We approached Smith to be interviewed about whether CRS had made organisational changes, and he refused to comment.

In the wake of Smith’s lack of response, an industry insider sends me the link to CRS’s new Code of Conduct, on their website under Culture. Is it enough?

Performing artist Lydia Cole says, “While I'm not going to comment on everything that CRS have or haven't done throughout all this, I will say that I feel there is plenty of room left for genuine, transparent communication from them, something other than a carefully produced statement."

Cole makes it clear that this level of accountability is vital for industry change.

“Right now, this is the only thing that will give me hope that our industry is any safer now than it was a year ago. No number of investigations, company statements, personal apologies or codes of conduct will do that for me.”