Everything you want to know about Hera Lindsay Bird

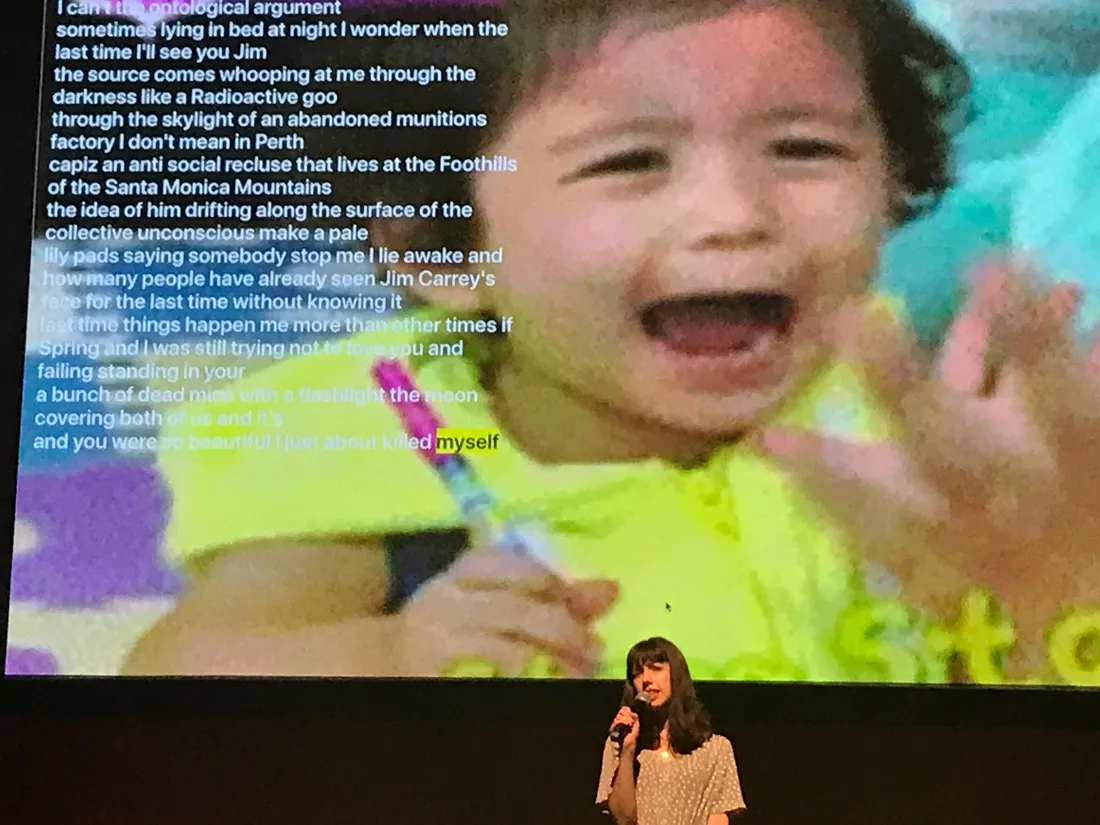

Hera Lindsay Bird is a poet. In 2016 her book Hera Lindsay Bird won her an Ockham award for the best first book of poetry, and an instant reputation for daring to have fun with poetry.

Earlier this year, she and James Littlewood sat on a couch at the Semipermanent conference for fifteen minutes while he asked her some questions.

How important is poetry?

As a writer I feel like I’m not really invested in poetry as a form. Poetry was good for me because I have a short attention span. So you can write short poems, and you can sort of move on, you know. You don’t have to hit the same kind of sustained discipline as writing a novel. It’s more acceptable to write your own personal life, maybe.

But I think the thing poetry also does, which is not always so easy in other writing disciplines, is - I love things like non-sequiturs, strange emotional shifts and things like that, and that suits poetry quite well.

Do you see yourself as a storyteller?

I love reading story, I love genre fiction. Sci fi, crime, fantasy, stuff like that. But in the rest of my life I’m not very invested in the idea of story, because mostly there isn’t one. I mean it depends who you are I guess. Maybe if you’ve got an identical twin who robs a bank or you’re going off to war, something in your life maybe has more elements of story in it.

My favourite night is 7pm watching University Challenge at home and going to bed early.

But to me it’s important to find a way to talk honestly about what life feels like. And if your life doesn’t have a lot of plot, what do you do with that? Write poetry.

Your poetry has lots of sex in it, and you play quite a few gigs. Does it feel like rock’n’roll to you?

No! Not really, no! I’m the least rock’n’roll person in the world. Like, my favourite night is 7pm watching University Challenge at home and going to bed early. I do like performing. And the best part is when I get to do things that kind of exist outside of the poetry world. Like I got to perform with Aldous Harding once, and Nadia Reid, and people like that. And so that’s my way of like being like a rock star temp.

Poetry has a proud history of filth and debauchery.

How do you see your poetry within the greater body of the artform?

I reckon it’s funny because if you mention sex or drugs or rock n roll or whatever, there’s been a weird reaction where people kind of think that it’s like non traditional poetry. But actually if you look at the entire history of poetry, that’s all it is. Like go back to Catullus, he’s like the great ancient Roman poet who like wrote the most bawdy, disgusting poems imaginable. Poetry has a proud history of filth and debauchery. So it only became this more genteel, la-de-da kind of thing maybe with the romantics. Like if you go back to Homer and stuff like that, there’s nothing sanitised or neat about it.

If you talk about it with your friends, you should be able to put it in a poem.

How important are the rules of verse?

Well I don’t really write in any traditional poetry formations. There’s this really amazing book that I love called Drunk Sonnets by a guy called Daniel Bayley, who got really drunk and wrote a whole entire book full of sonnets. Some of them are terrible, but he’s writing drunk, what can you expect? But mostly I just kind of write free verse, because that’s what I grew up reading, and that’s what the poets I love wrote.

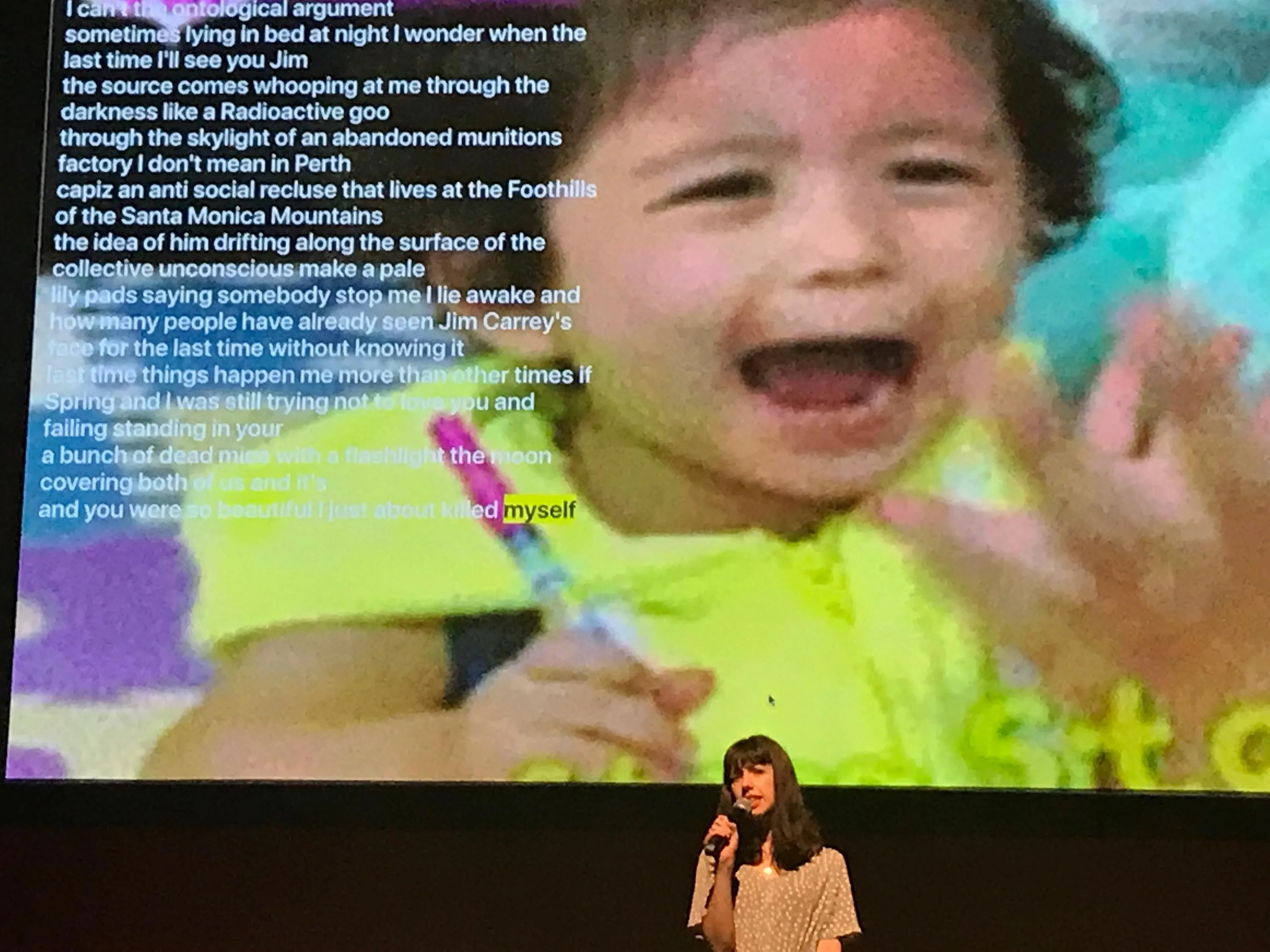

I love long poems, and I love the long line, and the uncomfortably long sentence that goes on for longer than it should. To me there’s a lot of humour in that. It doesn’t really fit within a more narrow or traditional poetry format.

Some of your work is laugh-out-loud funny.

Comedy is an important part of poetry for me. Not for everyone. But all the writing I love in the world, whether it’s heavy, YouTube gamers, short stories, novels, fiction, all the stuff I love the most is humour, and it kind of took me a while to figure that out. All the stuff I wrote in high school was sort of jokey, funny. And when I went to the IIML [International Institute of Modern Letters at University of Wellington] I was trying to do the serious poet thing. Eventually I was like, why am I doing this? I wouldn’t read this. I live for the jokes.

It kind of feels a little bit transgressive sometimes, because with poetry there’s that uncertainty about whether something’s a joke or whether it’s sentimental. It means people don’t really know what you’re gonna do, you know.

If I’m writing about myself I don’t have a lot of shame about that stuff.

If your work is confrontational, that’s probably because of the honesty in it. Is it about honesty or exhibitionism?

What, specifically?

Like The Keats poem, I guess?

To me that’s like a carpe diem poem.

What’s a carpe diem poem?

It’s kind of weird because when I published that everyone read it like a very serious attack on the literary establishment. You’re taking Keats down, and Wordsworth. And I was like, no, those were people I loved when I grew up reading. You know, you can make fun of the great poets of history dying but there’s still a fondness there. And to me that poem is a poem about poetry. You know, like what do you do when all the old masters are dead? Where do you go? But you know, I dunno, most of my poems have some element of love or relationships or sex in them, or something like that.

Do you have to double check yourself when you deal with something very personal?

Not really. Like I think that if I’m writing about other people then I'm more careful. If I’m writing about myself I don’t have a lot of shame about that stuff. People don’t expect it because it’s in the context of poetry. But I don’t think it’s more shocking than what you’d talk about with your friends. If you talk about it with your friends, you should be able to put it in a poem. Otherwise, what are you going to write about? The rolling hills?

Hera Lindsay Bird's second book Pamper Me to Hell and Back is described with undue modesty as “a startling departure from her bestselling debut Hera Lindsay Bird by defying convention and remaining exactly the same, only worse.”