First Glimpse at Yuki Kihara's Venice Biennale Project

Sāmoan artist Yuki Kihara draws on her perspective as fa’afafine to confront colonisation and climate crisis with her work Paradise Camp for New Zealand pavilion at the Venice Biennale.

Paradise Camp will be shown in a central location in the Arsenale at the 59th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia (Biennale Arte 2022) - opening to the public for seven months from April 23.

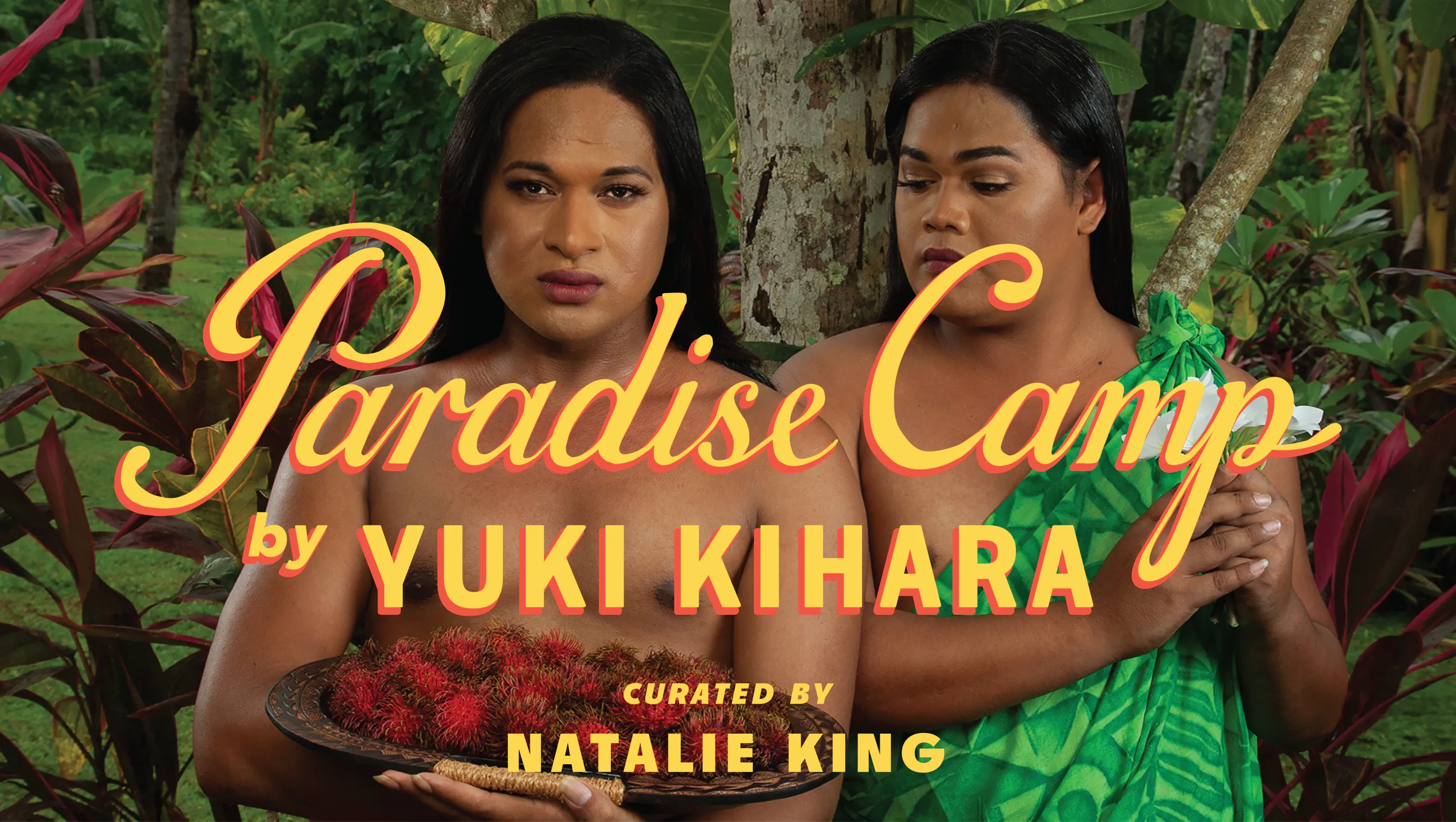

Creative New Zealand is keeping the full details close to its chest - but have released a first glimpse at Paradise Camp via an image Two faʻafafine (After Gauguin) [2020] which shows two fa’afafine holding a wooden bowl of red fruit and a white flower against a backdrop of wide, waxy leaves and tree trunks.

It is beautiful, but uncomfortable to look at.

Kihara draws on the paintings Post-Impressionist French painter Paul Gauguin did in Tahiti, often of mahu (Tahitian third gender) and young teenage girls.

A New York Times essay asks whether it is time for Gauguin to be cancelled, explaining that he had sex with the 13 and 14-year-old girls that he painted. Sāmoan art writer Lana Lopesi writes that the ‘dusky maiden’ trope used by Gauguin to depict Moana women as sexual and innocent was dehumanising and is part of broader colonial processes with far-reaching effects.

Back in 2008, Kihara was in New York for a solo exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. There she viewed Gauguin’s paintings (like this one I think Paradise Camp evokes – it has a similar fruit and flowers). She remembered an unpublished essay by Ngahuia Te Awekotuku from the early 90s that considered Gauguin from an indigenous perspective.

Kihara says recent Western interest in fa’afafine (and other Moana queer peoples) through documentary, anthropology and travel writing is a “neo-colonial tactic” that began with explorers and missionaries.

Instead, her work subverts the Western gaze. A fa’afafine artist looks back at Gauguin.

Yuki Kihara at the opening of her exhibition in Pataka: サ-モアのうた (Sāmoa no uta) A Song About Sāmoa. Photo: Creative New Zealand.

Sāmoan-born Kihara has a Japanese father and Sāmoan mother. In 2001, her satirical tee-shirts at Te Papa caused a stir for messing with the slogans of corporate giants and being Pacific-centric (I remember seeing them and feeling elated). Her works, which often deal with racism and colonisation, are now held by renowned galleries worldwide including Te Papa Tongarewa Museum of New Zealand; Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, British Museum and Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts.

In a recent Woman magazine interview, Kihara explains she may have failed her first year of fashion school “because in that first year all I did was party and get drunk." That’s hard to believe because in video interviews, she comes across as thoughtful and poised – even powerful.

I asked Kihara about the advice she would give young queer people of colour about surviving as an artist. She says, “Age and experience are two different things; so be careful who you seek advice from”.

Being fa’afafine has led to creative and critical insight, she tells The Big Idea “‘the fa’afafine lens’ for me is about having a ʻthird eye’ or a consciousness to look beyond the ordinary sight to question the power dynamics behind how we occupy the world we all share together.”

Yuki Kihara as Salome in performance. Photo: Luke Williamson.

Paradise Camp was shot and filmed on location in Upolu Island, Sāmoa, with a local cast and crew of over 80 people, many of whom are fa’afafine and fa’atama. A high chief from the Aleipata district, Letiu Lee Palupe, was cultural advisor.

The climate threat faced by Sāmoa is a significant aspect of Pacific Camp. Kihara says living in Sāmoa over the last 12 years, she has experienced rising sea levels and extreme weather. “I constantly have to repair our family home after every cyclone.”

Kihara points out that, like Gauguin’s exotifying gaze, massive carbon emissions started with the West. Certainly, the new Climate Transparency Report 2021 shows the carbon emissions of G20 countries are likely to prevent us from meeting the UN targets of preventing 1.5 degrees of global warming.

Yuki Kihara and Natalie King. Photo: Evotia Tamua.

Australian Curator Natalie King says, “Kihara narrates stories of invasion and prejudice and in so doing, takes the tempo of our times by unravelling colonial histories linked with gender politics and environmental concerns.”

Following in the footsteps of highly-regarded creatives like Dane Mitchell, Lisa Reihana, Simon Denny, Bill Culbert and Michael Parekowhai in being selected to represent New Zealand, Kihara states the Faʻafafine and Faʻatama community is her primary audience. “If they feel empowered by Paradise Camp then I think I’ve done my job.”

Yet at the preeminent art exhibition in the heart of Europe, Pacific Camp might hit closer to home.

Gauguin paintings are still shown at major galleries. Artnews reports a painting by Gauguin during his Tahitian period sold for €9.5 million (NZ $15,659,291.86 ) at a Paris auction in 2019.

The world’s leading contemporary arts forum will see that perspective - among many others - challenged by Kihara’s politically charged project.