Fluid containers

Written by

It can be a penny arcade, a video arcade or a shopping arcade. It can be a series of arches – trajectories extending elegantly, briefly, repetitively from the norm. All meanings of the word arcade conjure up the eclecticism and fantasy of a festival.

The Performance Arcade is now in its sixth year. This live arts festival in and around a procession of containers on the Wellington waterfront during arts festival remains an ingenious format: an independent force to be reckoned with.

In 2016, 19 works were present for 26 hours over four days, with a live music series and bar. A development programme with public events led up to it over the summer. For the artists the Arcade allows for development and experimentation in the company of others, with intense interaction with a wide public. For the passerby, it’s an accessible way to engage with new ideas. Crucially, in public space, it is free.

It’s all in the experience: mine in 2015 was lackluster; the Arcade felt like it was getting spread a little thin. This year the programme feels more consolidated and effective as a whole. Director Sam Trubridge builds on his work with a range of artists from previous Arcades, while also supporting new blood. A company of artists has been created – an increasingly rare thing.

Live Arts stands for a wide swathe of work that still often fits outside the predetermined boxes – kinetic, sonic, design and performance based installations, walks and all manner of experiences. They sit best outside the theatre and gallery and their frames - feeding the environment in, and rebroadcasting.

Like any kind of arcade the weakness is the compressed format, with the next ‘arch’ always diverting your attention. It feels reflective of, rather than an antidote to, our online multitasking lives. It doesn’t favour narrative or conceptually layered work, or experiences requiring time – often a prerequisite for lasting art experiences. A range of works get around the time element – taking you off on walks (more on these later) or, in the case of Asylum, literally locking you in. Like a bigger festival like Splore, you’re best to devote some time to ambling.

It’s hard to keep one’s focus when the next sideshow is calling. Some works play to this, but I often find them unfulfilling. Aphelion from a design collective is in a long line of Arcade works that experiment with performance design with light and kinetic design elements – like a penny arcade slot machine that performs a short action, and you then walk on. Likewise Josephine Jowett‘s Parabox appeared on several visits simply an environment where the walls of the container are covered in torn strips of cardboard boxing. An environment without action: pop in, pop out. Reading the website text later I realised this was an example where a gallery context might have allowed quieter reflection of a much more complex back story.

The presentation of a documentary and video tutorials from Estonia’s Theatre No.99 about their creation of a fictitious political movement, the Unified Estonia Assembly, is also tricky in a container, and felt at odds thematically (meanwhile a screening of the full documentary was held at Nga Taonga during the week).

However, there were many works playing strongly to the format. Water and new ways to consider the surrounding natural environment provided the festival with a strong thematic thread.

The arcade in effect began with Julieanna Preston’s performance Water-logged, featuring Preston at regular times floating freely under the wharves near Te Papa, interacting with the Jarrah wharf piles. A video in a container above captures her bobbing in and out of frame. The work was strangely, gently resonant in its interaction with the underside.

Extending from this, three video works focused on breathing, water and marine life and were cleverly arranged in several connected containers as gallery space: Sally J Morgan and Jess Richards’ The Drowning (more interesting as a creative collaboration than for its actual effect) and the mesmerizing site-sensitive Chrysaora Colorata by Denise Batchelor and Wishing Well by Dani Terrizzi.

Kane Laing’s Water Bar was a great crowd puller. A free bar offered you a menu of diverse range of waters to sample. It was a simple idea executed well, with the different waters offered in a range of clever ways – sea water from Himatangi Beach served as shaved ice on a small spoon, thickened water offered chilled on porcelain, and a spray spritz of wild willow water from Iran, usually used for baking. A little jokey, but it suited the Arcade format and the underlying issues of water quality and sea level rise bubbled up in the white spaces of the menu.

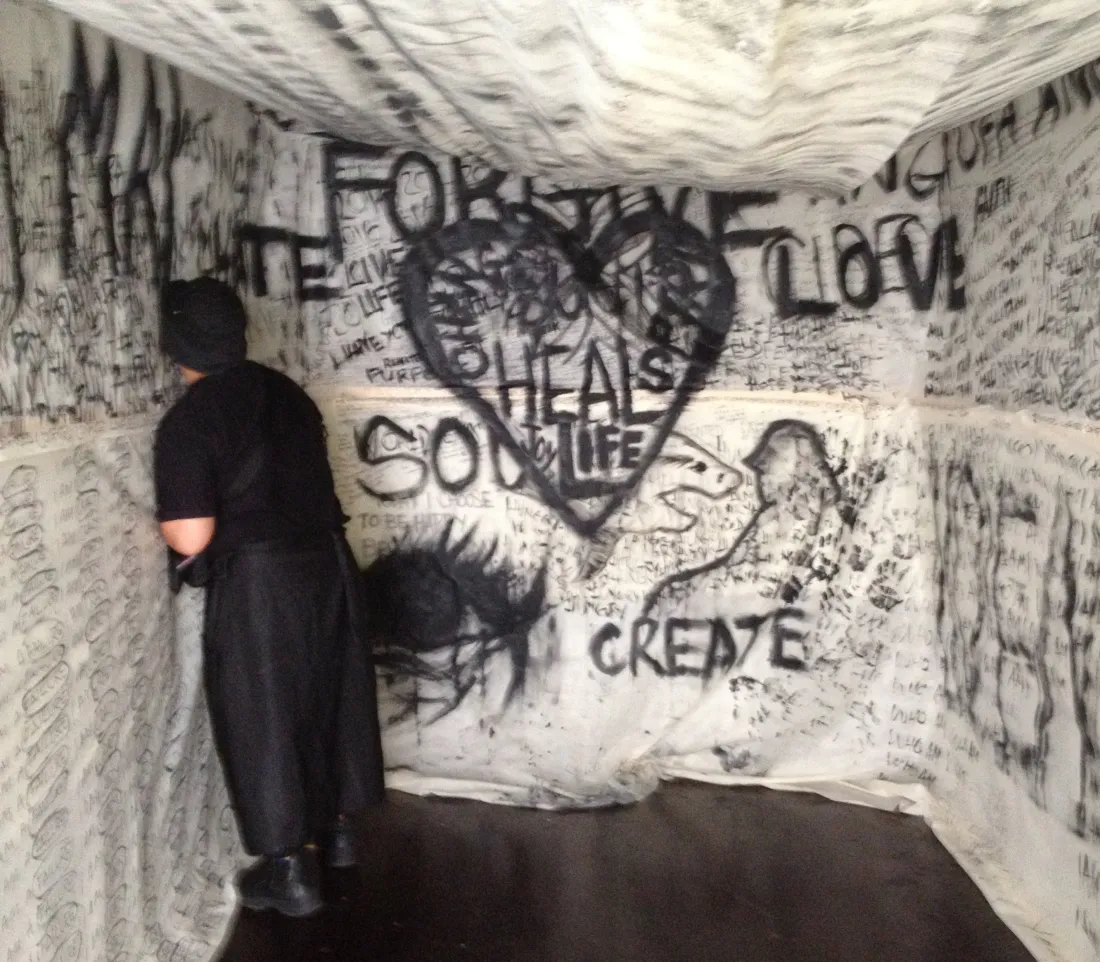

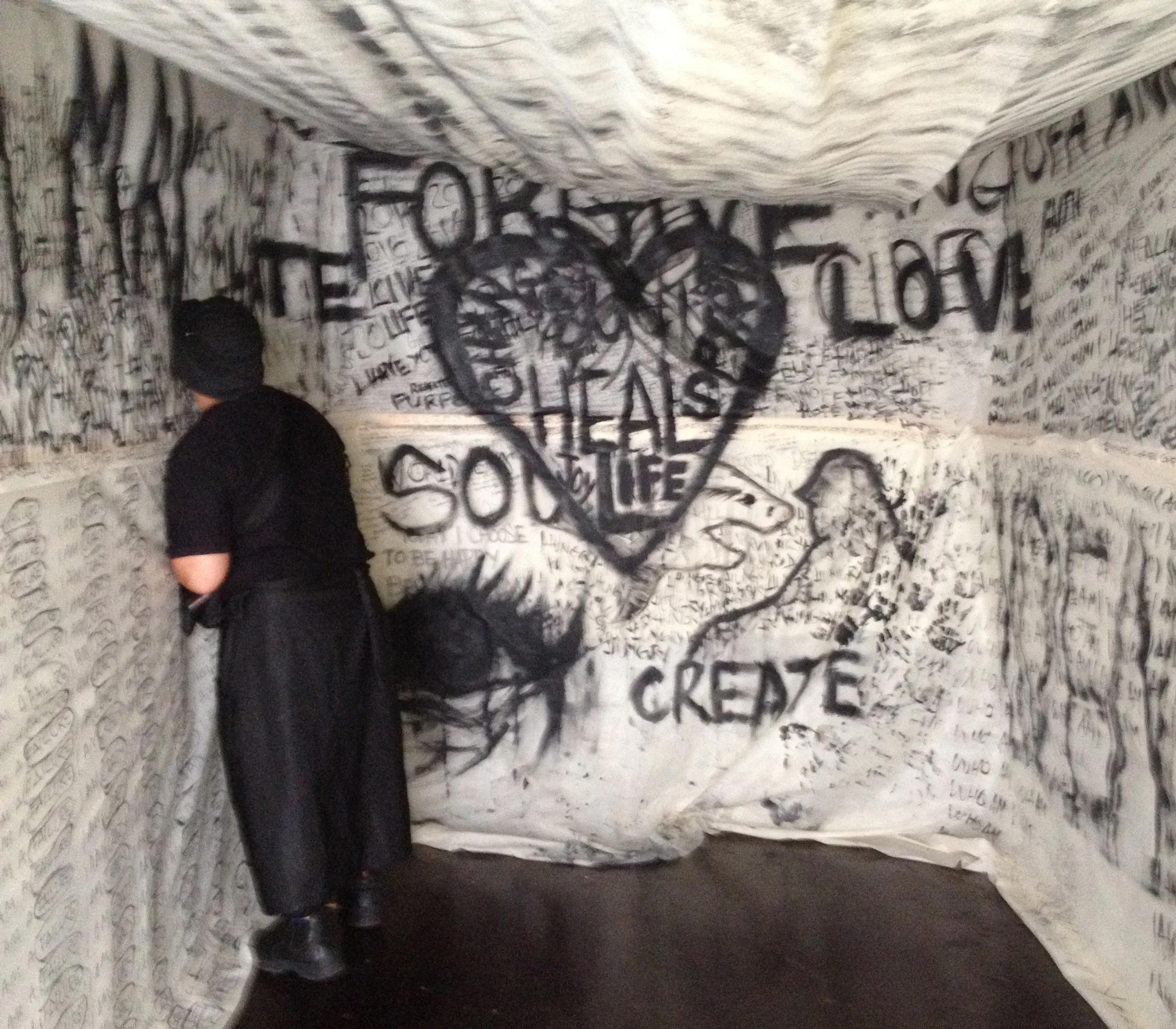

2015 Walters Award nominee Kalisolaite Uhila has cut his performance endurance teeth at the Arcade every year since 2011. In that first year he shared a container with pigs. In Ongo Mei Loto he shares it gently with us. A container set apart, you enter the dark and Uhila offers you a black marker, inviting you to add your expression to the walls. These walls are expressionistically smeared with existential cries for love and questionings of faith - an interactive McCahon. That might sound awfully clichéd, but in Uhila’s sensitive hands it’s a powerful, meditative space for facing fears for all-comers and feeling your environment: a dark, intimate sanctuary.

My favourite works sustain your attention by guiding you out into the urban environment beyond. For them the containers are a matter of convenience rather than necessity.

For The Body Cartography project with Footnote Dance Company Closer I booked in for a 15 minute one-on-one dance performance. My daughter and I were instructed to follow a dancer, as close or as distant as we wished. His expressive improvisation with different elements around the wonderful Megan Wraight-designed water-sensitive Waitangi Park provided a powerful way to unlock physical enjoyment of the corners and ledges of public space. I was reminded how close the language of dance is to that of natural childhood public space play.

Other works fruitfully use the Arcade as a starting point for walks that provide new understandings of our natural environment. The Stone Unturned saw Angela Kilford and Elijah Winter invite you on walks to consider the living environment from a whakapapa perspective, or engage in the weaving of harakeke with weavers from Hikoihikoi Petone, the mouth of the Hutt River.

I wasn’t able to attend, but I did spend an hour getting to know the city’s pigeons better. In Hello Pigeons Adam Ben-Dror and Kedron Parker lead you to Te Aro Park, often known as Pigeon Park, inviting you to consider the flocks of pigeons you see along the way. There as a group we undertake various tasks feeding pigeons to consider their behaviour, before being given the opportunity to hold close a pigeon (a racing pigeon from Paraparaumu) and release it. It’s a lovely experience, beautifully handled, making you consider the beauty and nobility of birds we have classed ‘rats with wings’. But it stops short of providing a scenario that is more challenging or encouraging deeper thought about the relationship between the wild and domesticated, indigenous and imported.

The biggest hurdle for The Performance Arcade in its sixth year is a sense of déjà vu borne of the format staying the same and Trubridge curating every year. While this provides invaluable continuity and artist support, there also becomes a sameness: a robotic drawing machine here, an abstract video work or piece of performance design there. The Arcade might benefit from a fresh curatorial perspective, or commissioning more directly on its themes to provide more edge. Those things however require better funding. These are the challenges every art organisation faces, settling into becoming a valuable institution.