Getting Physical

Written by

Mark Amery on three artists who are proving that messy gutsy painting is holding its own.

* * *

Welcome the crumbly and the globby, the messy and the uneven. In recent years we’ve been seeing an increasing amount of art that carries a physical, material wallop. Rougher, muckier surfaces and joints where objects bear the imprint of their making. Earthier abstractions. Art working in counter to the sheen of screens, and their overload of data, graphic and photographic representation. Reactive too against the slickness of much contemporary art, this is expressive work that harks back - remember the coarseness of hessian? - but with a new impulse.

Walker Going over

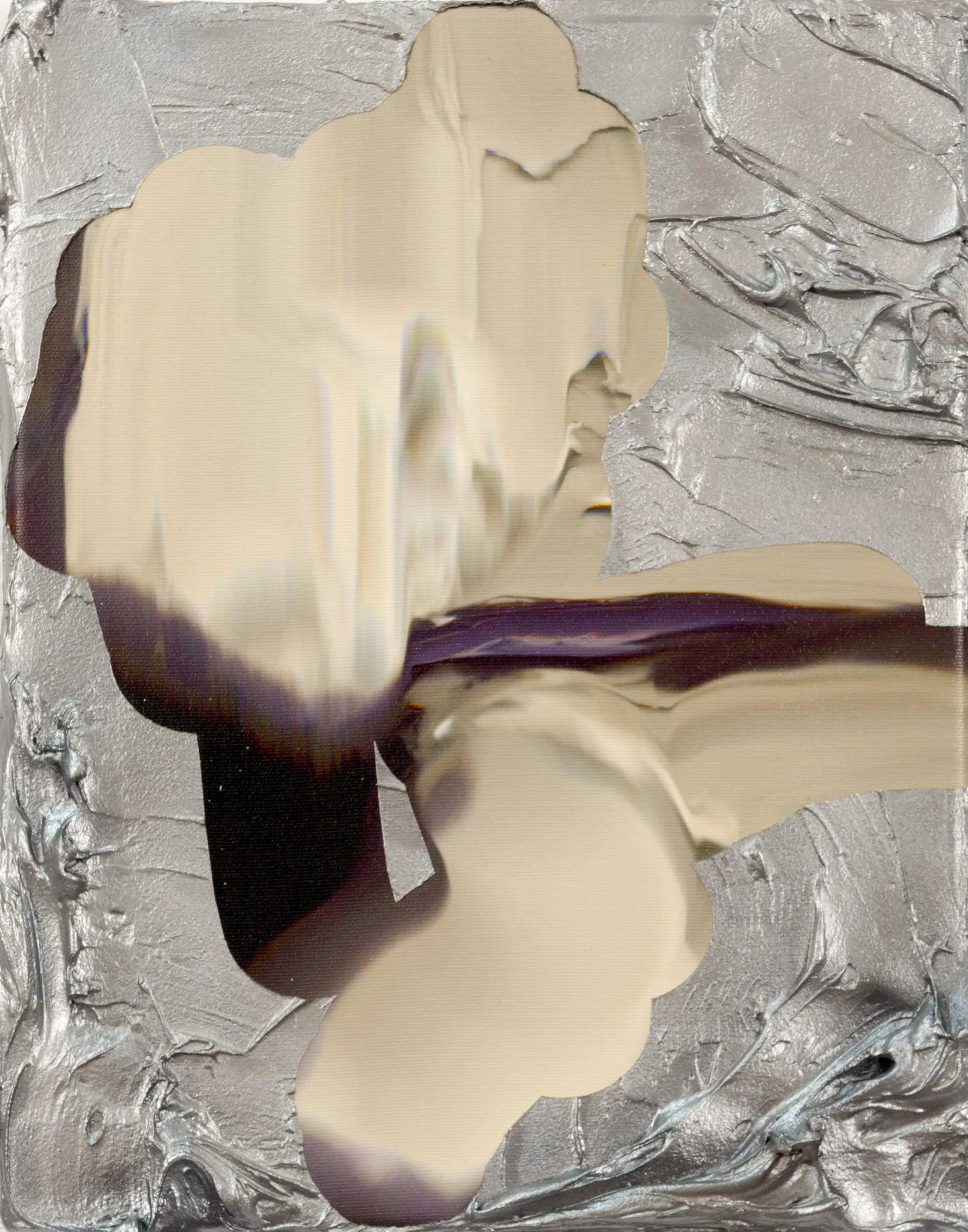

There’s been a renewed interest in ceramics. Rather distinctively, Jake Walker (back living in New Zealand after years in Melbourne) is combining clay with painting, as well as creating his own ceramic works. Currently on show at The Young in Wellington, are thickly laid, abstract oils often framed by being placed within glazed stoneware dishes. Others are framed in wood, but it’s the ceramic-held works that have the charge for me.

I say ‘held’ because with the wobbly undulating line and rugged surface of the clay there is the sense of physical human containment - a holding and channeling of the environment. Within are rough layers of paint. Sometimes lighter, brighter patchworks of colour and shape are overlaid with thicker black squares, other times the whole surface has become a slab of bitumen-like black. Shapes like symbols are just discernible as imprints in the underlay. There is the sense of accretion of time, of meanings being buried in a compact of layers.

The more colourful, patchy works are less interesting to me - they are more familiar, uncertain abstractions. What is fresh and strong is the treatment of the painting as object - an object that is ever deteriorating in the face of nature, rather than ever new. It is as if these works have been torn out of a built industrial environment, with its web of pipes and robust but worn surfaces.

There is a landscape of marks evocative of human stories, but nature passes through and is contained by a construction. Sometimes the ceramic frames are rather effectively, broken, craggy sections of pipe with open portals, empty channels for the input of new meanings for the viewer. In the ‘Ohakuri Dam’ works ridges on the top of the frame suggest channels that were once functional, but now hold resonance in the abstract.

These landscape-shaped works of Walker’s are the size of a laptop screen. They ask to be treated as reading devices, yet confront you with what might initially be considered blank screens. Instead they demand to be read viscerally, physically, offering an encounter different to that provided digitally.

Hemer's new Representations

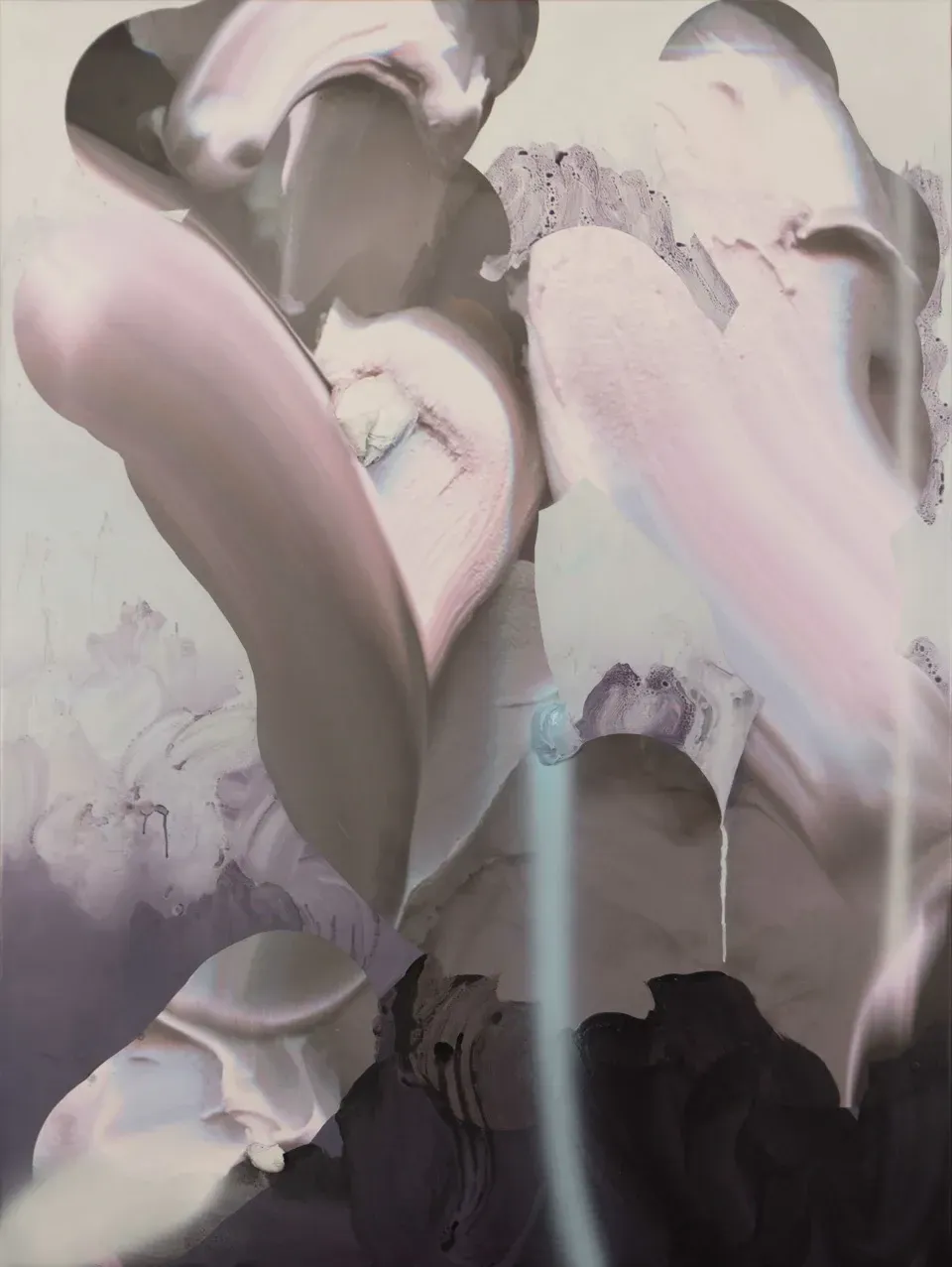

Over more than ten years Andre Hemer has been exploring the tension between a painting as image and object in the digital age. Increasingly effectively, he takes the language and cut and paste, swipe and scan tools of the screen, and explores how it might have a charged material manifestation.

As with Walker, the work encourages us to respond to the world more physically and sensually, but with no lack of visual complexity. Hemer’s work graces the cover of an October 2014 published Thames and Hudson book 100 Painters of Tomorrow. He is increasingly getting significant opportunities in Europe and Australia (where he is now based). With an impressive new exhibition at Bartley and Company you can see why.

This is spunky, gutsy painting, as luscious as icecream, as richly delicately coloured as roses, with the electric strobe light of the digital. Big thick gestural marks ala Judy Millar dominate, in this his most painterly work, yet it’s only when you see the work off the screen and on the wall that you truly grasp the adventurous play between impasto paint on the surface and the digital printing of paint. This meld of the physical and digital, cutting into the surface and overlaying, is now incredibly sophisticated as well as playful. It gives these works a grunt as objects, in their smart but fluid compositional tensions that I’ve not always felt with Hemer’s work before.

Macleod's Rope

It’s interesting to consider these younger painters alongside new work at Bowen Galleries of Euan MacLeod, who remains one of our gutsiest most eloquent expressive painters. Long resident in Sydney, MacLeod has continued to show consistently in New Zealand since the early 1980s and his work reflects a deep engagement with this landscape.

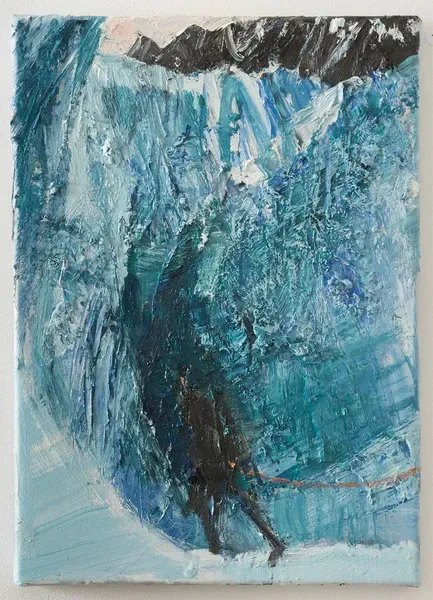

In Macleod’s work a lone everyman figure is both giant bestriding our imposing landscape and a figure being subsumed by it. In dreamlike narratives of shifting scales, and ghostlike encounters the paintings speak of our relationship to the land, and our varied emotional states, but they also speak of the sense that we are ultimately of the earth itself. The figure is the artist, the artist is ourselves, we are part of the painting. McLeod’s figures are just as often rubbed away elements of the landscape, as they are elements painted on top.

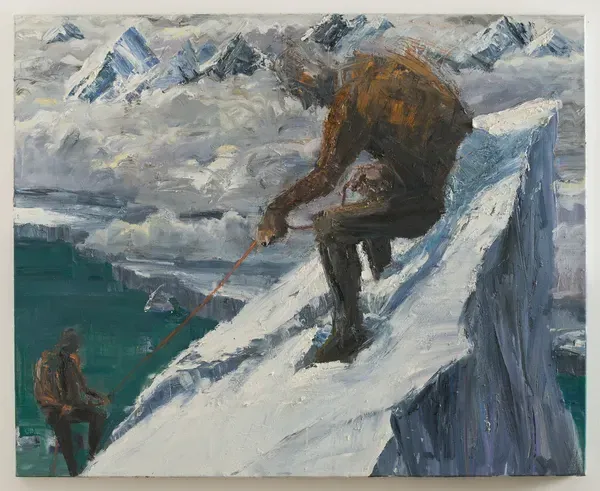

The exhibition ‘Rope’ depicts a mountaineer who, usually alone, climbs and crosses an icy mountainous landscape. Typically, an orange rope passes from the figure out of each frame to an unseen other. Smartly, it reappears in the next painting, as if this is one narrative - yet as if in a dream the scale is constantly altering. The line provides a literal tension and a metaphor for human endeavour: our everyman must always be striving forward, yet relies on unseen support.

Macleod’s work has continued to strengthen in its distinctive dynamic meld of abstraction, the figurative and landscape. His thick use of paint is alive and texturally complex, yet in the best work all coheres. Like Hemer the different modes of application are diverse, and audaciously balanced.

In the small work ‘Snow Cave’ a figure leads us into a dynamic morass of abstraction – we disappear into ourselves. In the larger ‘Head in Clouds’ an avalanche of muck invades from the top left corner, in tenuous but strong tension with the compositional whole.

MacLeod’s work is as much about the expressive weight of the material and how it might be employed in the abstract, as it is what he is depicting. In ‘Ice Fall’ a small figure just holding onto a rope leads us on top of a mighty crackling heave of fracturing ice slabs to balance, before a swirl of icy fluid in the background. As material the adroit use of paint to depict ice speaks of climate change, but also of the intangible psychic shifts we feel ourselves as we try to keep our footing.

A survey exhibition of McLeod’s work, which opened over summer at Tauranga Art Gallery, is now showing at the Waikato Art Museum. It’s easy to think we might be done with big expressionistic painting, that it’s old hat. Yet MacLeod continues to find vitality. Here’s the hope big city curators look beyond just the media and work that is in vogue, to ensure the public in the big cities get to see a survey like this. As our visual culture gets increasingly more digital, the value of rich intelligent play with material only gets higher.

- Going Over, Jake Walker, The Young, Wellington until 25 April

- New Representation Part 2, Andre Hemer, Bartley and Company, Wellington, until 2 May

- Rope, Euan Macleod, Bowen Galleries, Wellington, until 2 May.

- The Painter in the Painting, Euan Macleod, Waikato Museum, Hamilton, until 5 July