NZ Fest Digest: Time's Shape

Written by

By Renee Gerlich, NZ Festival Writers Week

When confronted with the vision of a bush in flames but not being burned, Moses asked it: “What is your name?”

Historian Diarmaid MacCulloch explains in his talk on Christianity that there are two possible translations of the bush's reply, the bush being of course of the Old Testament Hebrew speaking variety. “I am who I am,” is one, or alternatively: “I will be what I will be.” Both are presumably mistranslations, insufficient representations of the original text. Nevertheless, MacCulloch gives us an interesting problem to cope with in our own syntax. Then Lloyd Jones says in the Pacific Highways presentation, that each person is really two: “the person they once were, and the person they are becoming.”

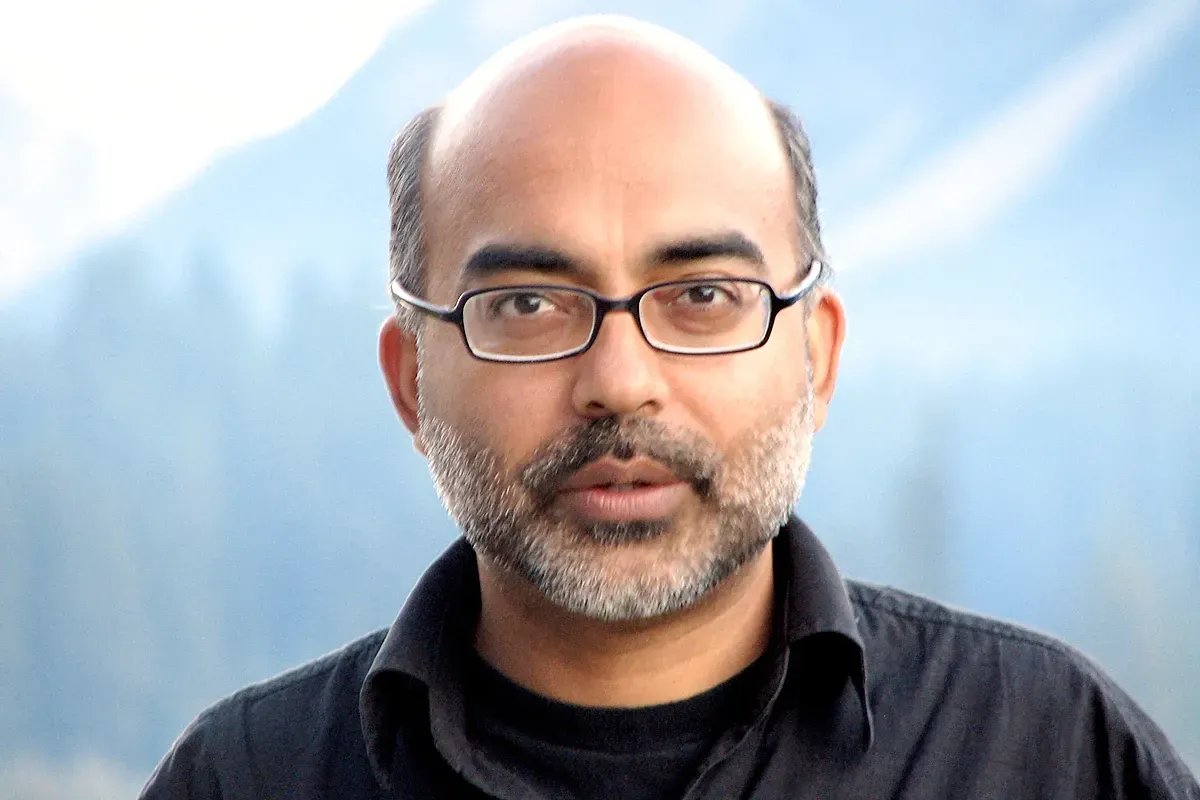

The themes of historical awareness, presence and transformation are grappled with in many Writers' Week events, notably Eleanor Catton's lecture, which focuses mainly on the transformative forward movement of plot in fiction writing. Interesting to hear three historians reflecting the day after Catton's talk on the role of the past: MacCulloch, as well as novelists Jaspreet Singh and Kei Miller.

Each of these writers too affirm the role of identity in driving writing and inquiry: Singh and Miller are both critically concerned with the histories of their respective countries of origin. The theme of MacCulloch's last book is silence, which as a homosexual in the church has some personal resonance. MacCulloch is a deacon, historian and “candid friend” to the Anglican church who sees it as his role “to tell it home truths”. He says that past and future (“what was” and “what should be”) are often intimately entangled, naming Nazi Germany, Putin's Russia and the Rwandan genocide as episodes in which “bad histories” have helped perpetrators gain support in committing crimes against humanity. It is vital we maintain accurate conceptions of history.

Yet “history is happenstance” he says, and the past is strange and surreal. In telling it, the strangeness of the proclamations that remain still, embedded in our institutions, are also revealed. Miller echoes this idea when he explains that he chooses to write fiction in part because he finds so much of the abhorrent circumstances of which he writes, including those created by homophobia, “to have the quality of fiction” in their absurdity.

Singh too is a fiction writer responding to socio-political calamities. His notion of history seems less based on happenstance than MacCulloch's though, more on continued, systemic abuse of institutional power to protect privilege. His novel Helium exposes the genocide of Sikhs facilitated by Indian leaders in November 1984, which he survived as a teenager. This event is still silenced in India, and perpetrators still in power. Singh is a whistleblower.

A human rights report, he says, would not achieve that to which he aspired. He chose to write a novel since histories “can be told unlovingly and without empathy if not told right” and the novel would best avoid those traps. Singh informed his work with interviews and extensive research. Because of the interviews, Singh says his work is more “traumatic memory” than historical fiction. His protagonist, having survived atrocities and witnessed the burning of books, becomes an archivist who also paints birds, paintings Singh calls her “daily exorcisms”

Miller too says although he is normally a pretty “funny guy”, his writing is deeply dark. While Singh is taking a break from historical writing, Miller says he turned to comedy (as in The Same Earth) after finding this darkness too big a burden. Eleanor Catton would perhaps vouch for this choice, given her long defence of Shakespeare's comedies in relation to his more celebrated tragedies. Catton affirms the comedies as those stories in which the protagonist is the most affirming, ingenious and gains the most insight through triumph.

What can be concluded from all of this... perhaps that the world needs more critical, well-researched historical satire that is lovingly written. Excellent.