Rangatahi rising: Mātauranga and education at Wairau Māori Art Gallery

Every week, school students walk through the doors of Wairau. What do the education programmes offer them?

Wairau Māori Art Gallery is the first of its kind in Aotearoa – a public gallery dedicated to contemporary Māori art. When it opened in 2022 within the Hundertwasser Art Centre in Whangārei, the world was in the grips of the COVID-19 pandemic and the gallery received less attention than it warranted. Since then, however, Wairau’s profile has grown. Under the Directorship of Te Ringa Hautu Toi: Larissa McMillan (Ngāpuhi, Te Parawhau), Wairau has seen an impressive run of solo and group shows by contemporary Māori artists, and fostered conversations with communities in Te Tai Tokerau and beyond.

Wairau’s operations are independent and self-determined – observing mana motuhake – evidenced by a wholly Māori rōpū comprising its governance (the Wairau Māori Art Gallery Trust Board, working alongside hapū Te Parawhau as mana whenua) and employees. The Trust boasts a cohort of acclaimed Māori art practitioners and industry leaders. Chair Elizabeth Ellis, CNZM and Senior New Zealander of the Year (2025), is accompanied by celebrated arts luminaries Lisa Reihana MNZM, Nigel Borrell MNZM, Karl Chitham ONZM and Dr Ngāhuia Harrison, among others.

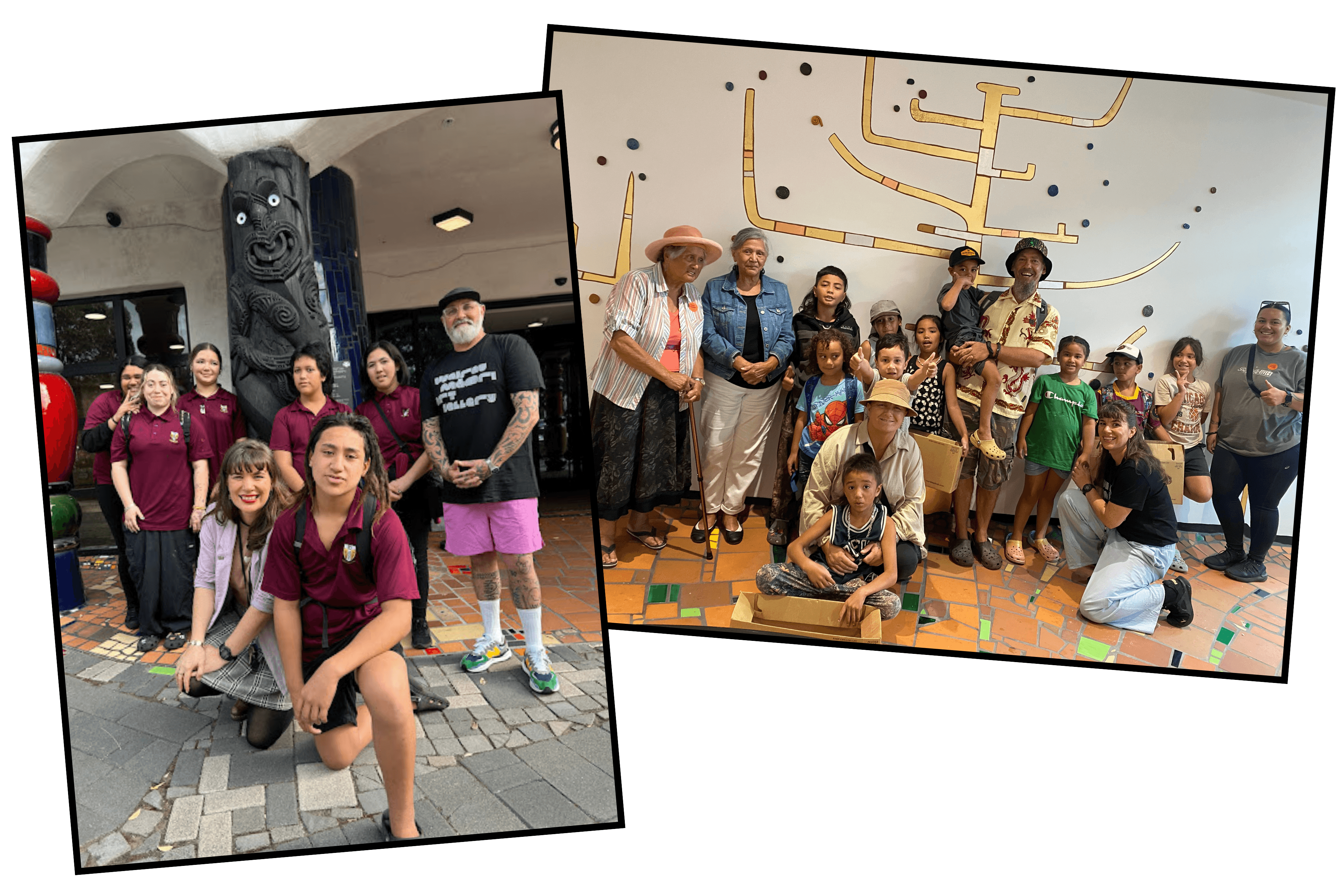

Every week, school students walk through the doors of Wairau. Taking a Māori approach to curating, exhibiting and promoting toi Māori means Wairau is centred on whakapapa and whanaungatanga. A significant element of this approach involves the sharing of mātauranga with rangatahi and other community groups, led by Kaimānga Mātauranga: Geva Downey (Ngāti Porou ki Hauraki, Ngāti Tamatēra, Ngāti Awa) – a visual arts educator bringing two decades of experience in gallery education. “It's been massively successful in motivating rangatahi to work on their goals, but also to see something bigger” she says. “They're inspired and amped up after talking about the art and engaging with ideas; stepping outside what may be going on in their worlds.”

Involving the Te Tai Tokerau community is fundamental to Wairau’s principles. “A good way of describing it is how manaakitanga is approached”, Geva explains. “[Wairau] is a small team and we know how important it is to connect whanaungatanga with the artworks that are relevant to their histories and the places they are from.”

Wairau partner with rangatahi, kaiawhina and kaiako from local kura as well as collaborating with peers such as ĀKAU, Te Ora Hou, Kura Aho Weavers Collective and I Have A Dream. Guests at Wairau learn about te ao o toi Māori as well as participating in their own creative practice to explore identity, place and whakapapa. Waiata and mōteatea are also common. “When we as Tangata Whenua engage taitamariki with the art in the gallery, sometimes the response is not discursive”, says Geva. “Sometimes it's best summarised with waiata.”

A trip to Wairau is a community experience for rangatahi. “It is a shared experience that uplifts the entire collective”, Geva explains. “We’ll put money towards paying for the bus to bring in a kura. We wrap-around to make sure that the many people involved in a young person’s life can participate – that means the bus driver too. We have a shared kai and we send them away with resources so they can do it again back at school. All of that care is necessary otherwise the conversation about the artworks can continue to rotate in circles and spheres that are disconnected from our whānau.”

This approach acknowledges the mauri of mahi toi as taonga for us all. “We all carry mauri within us and it resonates with people, the space, the works, the intentions of the artist. What mauri do you carry with you?” asks Geva. “When Tane was walking through the ngahere, he would karakia on certain parts of the ground and then mauri would rise up or be placed into stones or into spaces. The energy that you bring into something, it adds to the life force and nothing is inconsequential.”

There are other whānau that Wairau serve, like the kaiako in the region, and the gallery has strong relationships with the Art Teachers Association. “We value and are enriched by our close reciprocal working relationships with the teachers in our region”, says Geva. Kaiako Te Tai Tokerau have long been in need of accessible, online content that voices concepts, processes and ideas around art. “That’s the format that secondary school art teachers share with their students. It [social media] is the platform that their students are familiar with.”

Hosted on Wairau social media channels, Geva delivers warm, dynamic gallery walk through videos (complete with matching outfits). It was quickly realised that not just schools were engaging with the videos. “When we go into the back door and check out who's watching, it’s art institution practitioners and young creatives. That's the outstanding demographic engagement and it's huge. It proves that there is a gap in representation. Who are we used to seeing talk about art on our screens? What kind of art are we used to seeing?”

Geva doesn’t take the challenge of sharing mātauranga lightly. “It's scary for me, because under-representation and misrepresentation of Māori artists and their work has happened for so long. The thought of adding to a pile of irrelevant content is something that keeps me humbled and conscientious.” But Geva’s drive to share the work of contemporary Māori artists makes it worthwhile. “Delivering the depth of the artist’s message in a three minute reel can only do so much, but hopefully it lets people access their amazing work and connects them with the ideas.”

For Wairau, the goal of representing artists authentically is where the real stakes lie – rather than followingtypical conventions of institutional practices. “Historically, art institutions have been quite complicated and problematic for Māori,” says Geva. The Wairau team work with sensitivity and care to ensure the artists’ mana and that of the taonga they care for is upheld.

Wairau also work with specific rangatahi directly on their efforts to re-engage with the education system if high truancy is a feature. “We're here for the community. There's a programme where kids work towards their goal of showing up to school, and the reward is that they get to come in to Wairau to do art games together”, says Geva. “Then we go and have a hot chocolate together, and then talk about what they want their life to be like after high school.” They talk about identity and their aspirations. “What kind of things help remind you of who you are? Often, their answers really surprise me.”

Financial struggles can be a reality for many in Te Tai Tokerau, including students who show huge creative promise and drive. Wairau currently collaborates with Whangārei Art Museum in offering NCEA credits for work experience placements. In the future, they hope to offer paid internships to students that want to build on areas they excel in.

Artists such as Wayne Youle, Gina Matchitt, Turumeke Harrington, and James Ormsby have all delivered workshops over the past year for tamariki, rangatahi and local creatives. Wairau also recently collaborated with the Te Tai Tokerau Teachers Association to bring multimedia artist Tia Barrett to Whangārei to deliver a professional development workshop. “It is rewarding connecting artists to our art teachers (who are most often practicing artists themselves) – and the class visits can provide a much needed boost for our kaiako who are in very demanding roles”, says Geva. Tia provided a moving image workshop for local high school students, including a hands-on stop-motion film session. “It was the students’ introduction to how an artist can develop a conceptual framework and use that to inform their art making.”

Reflecting on the depth, breadth and significance that Wairau’s education programmes clearly hold for the local community, Geva is clear. “We are very deliberate with our energy and resources. If we are to offer programming connected to the exhibitions it needs to allow for growth, learning and nourishment for those that attend, the hapori they are part of, our artists that help deliver wananga and ourselves as practitioners.”

The Wairau team are tightknit, and the pressures of living in Te Tai Tokerau are well understood by Wairau leaders. Reflection and whanaungatanga is built into the way Wairau operates, and it is evident that the people who work there trust each other deeply. This emphasis on ka mua, ka muri is extended to exhibiting artists, who receive ongoing updates and a collection of audience reflections, images, testimonials and surveys pertaining to their show. “Our artists have got to survive in our arts ecosystem too. And audience impact evidence is useful for them to use in funding applications and supports them to build a sustainable career.”

At Wairau’s opening in 2022, board member Dr Ngāhuia Harrison commented that Wairau will hopefully “be a seed for other regions in Aotearoa to set other spaces up like this, I think there is a real thirst, for not just Māori but pākehā, tauiwi of this country, wanting to see maori art to see toi Māori”. This is evidenced by the strong engagement with Wairau from artists, curators, educators and audiences around Aotearoa. “The amount of community organisations we partner with, and the wonderful support from other art institutions feels like we are growing in a steady and meaningful way”, says Geva. “I'd love to see more rangatahi talk about the art and make creative content, and share what they make in our workshops. Their stories are off the charts, and uniquely Māori. I think many people in Aotearoa would benefit from hearing and seeing them – how special they are.”