Reeling Around

Written by

Mark Amery considers an eccentric, frustrating but rewarding look at the relationship between cinema and painting.

* * *

Cinema and painting: what a great theme for an exhibition. Once again the Adam Art Gallery tackles a big, vital topic of wide interest, leaving you wondering why other institutions don’t muster the energy. Up at the university on the hill is a gallery full of fascinating historical and contemporary artwork.

You might be able to tell I’m lining you up some big buts. For, great parts do not always leads to a great whole. Cinema and Painting also proves too wayward in its path to meet the great expectations of its title. Self-described by the curators as “fundamentally eccentric”, it often frustrates just when you want it to reveal things about the rich relationship between the two media, or more simply introduce the history of experimental cinema, the subject with which it is most concerned. There is meanwhile only a nod of attention to the impact of film on painting. Generally the show has a few too many loose ends.

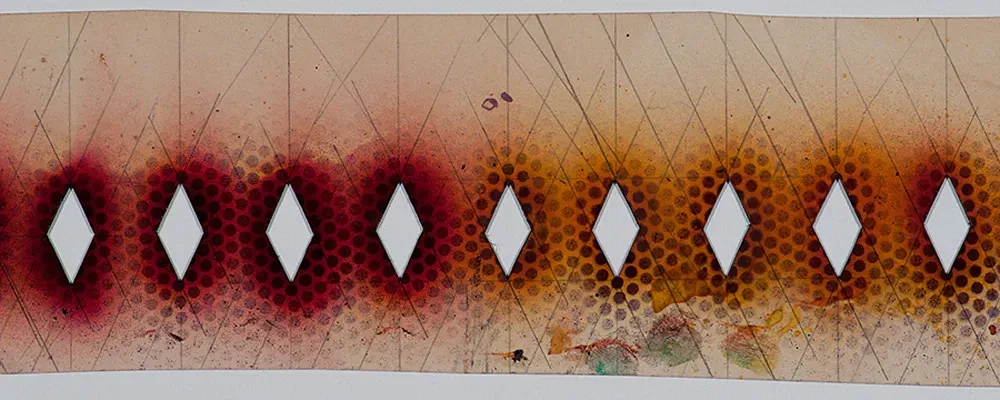

Forget the exhibition’s potential larger scope however and Cinema and Painting does have a strong well-curated core: abstraction in film. The exhibition is surprisingly sensual; the most painterly film show you’re likely to see. This intent is anchored by a large painting cum sculpture you encounter on entry, Judy Millar’s giant unfurling scroll Space Work 7. It is immediately get-able as luxuriant, rippling roll of film, suggesting film’s dazzling, malleable time and space based potential. It leads you grandly into the show rather than holds attention.

Round the corner Millar’s work is paired beautifully with Diana Thater’s Pink Daisies, Amber Room, a projection in a long space bathed in immersive orange light. In filming something as banal as an image of daisies Thater flattens her work of subject and narrative, and removes filmmaking’s conceit of representing the real. She instead explores the sensory, poetic potential of the camera moving over an expanded picture plane. This is cinema becoming painting.

Downstairs it is wonderful to see examples of Len Lye’s actual hand-painted pieces of celluloid (too often missing from Lye shows) and for Lye to be paired with another great abstract cinema artist, Oskar Fischinger. Unfortunate however is the way these singularly intense works play off each other and in the same room with contemporary filmmaker and painter Matt Saunder’s Century Rolls. All bleed into each other on the periphery of view, mixing the works into a noisy psychedelic stew.

The strength of providing discreet viewing areas for moving image work is made clear by the stunning presentation by itself of Phil Solomon’s terrific, elegiac 55 minute three-screen work American Falls in Adam’s Kirk Gallery. Solomon has transferred from digital back to celluloid major filmed moments from American history. Like a sculptor he has subjected them to chemical decay. To the distorted roar of a waterfall, history is captured as a dematerialising, burning torrent, a passionate expression of collective grief. As if we are in the eye of a storm, visual material bubbles elementally in and out of abstraction.

Level two of the gallery engages with the late 19th century beginnings of cinema, but this strand is not well tied in. Great to view Lumiere Company films for example, and I understand the intention to demonstrate their inheritance of the painting tradition, but there isn’t enough context with other work to do their inclusion’s justice. Instead, facing the Lumiere work are the mid 19th century New Zealand landscape watercolours of William Fox. Even with the catalogue explanation in hand I strained to make the connection.

And so it goes. Hollis Frampton’s A Lecture from 1968 is clearly key to the show but is inert in the exhibition as a script to thumb through. There is work of relevance by Colin McCahon (including previously unexhibited drawings), but little case made beyond his animation of the passing of time for privileging him above other painters. There are interesting scraps of Anthony McCall work, but they don’t connect in easily to the rest of the show. They feel like leftovers from his exhibition two years ago.

I’d far rather an exhibition provoked and agitated me than just led me down the same familiar boulevards. Ultimately, Cinema and Painting is as fascinating as it is frustrating.

- Cinema and Painting, Adam Art Gallery, until 11 May

MUST SEE:

The exhibition as compilation of diverse and well-constructed love songs: Douglas Stichbury is a smart, witty and elegant painter, finding visual poetry and poignancy in found imagery. He rummages through our collective image bank as if it were an op shop of tired knick-knacks, renewing them with fresh licks of paint, expressive pencil marks and judicious editing.

- The Practice of Leisure, Douglas Stichbury, Suite, until 26 April