Refractions of Light

Written by

Why did the man carrying a camera tripod cross the road? Because he was on his way to an exhibition of cameraless photography.

Bad joke, or bad conceptual performance artwork it’s what I saw last week on the way to Wellington’s Bartley and Company Gallery. Shaun Waugh was also on his way to the gallery - about to photograph, with a camera, documentation of the exhibition. And yes – hah - Waugh himself is an artist interested with his work in the conceptual boundaries of photography.

Like some beautiful accidental chemical bloom on a photographic plate, the encounter was happy happenstance.

Cameraless photography is exactly that: photographs made without a camera. Most commonly that is by the direct print contact of an object onto a piece of light-sensitive paper: such as you might make with your children as a home art-science experiment, or as in the now celebrated 1947 photograms of our own Len Lye.

Such photographs just predate the invention of the camera, but the practice has continued as a fascinating scientific and artistic slipstream. It was picked up by the avant-garde surrealists of the early 20th century, and has continued to be a field for adventurous artistic experimentation since. There is increasing interest from artists today.

Shaun Waugh is one of five contemporary New Zealand photographers featured in the sizeable and significant exhibition Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph at New Plymouth’s Govett Brewster Art Gallery. It is said to be the first comprehensive survey of cameraless photography held anywhere in the world, accompanied by a handsome history of the medium, written by the curator Geoffrey Batchen. Batchen is a professor in the history of photography at Victoria University.

Why might such an almost primitive approach be coming into focus now? As Batchen points out, cameraless photography retains a subversive position today by countering the digitally derived mass produced products of capitalism, and yet it can still engage adventurously with digital technology.

But there are other reasons. For the artist who has grown up on photoshop, collaging on the flat plane of the photogram makes complete sense. It is also a medium that can make the invisible visible: rather than the big ego writ large statements of late modernism, these works moreoften offer a quiet intimacy and focus on the microscopic movement that webs all things. The photogram offers a space attractive to the artist today in-between media: not quite photography, painting, sculpture or performance documentation.

What has been a fractured, scattered media for over 100 years might - when placed at the centre of art history now - offer new readings of art's vital relationship to the world around it, rather than just to itself.

Anticipating this is this smart substantial exhibition and publication in New Plymouth and a smaller exhibition in Wellington.

Local Emanations

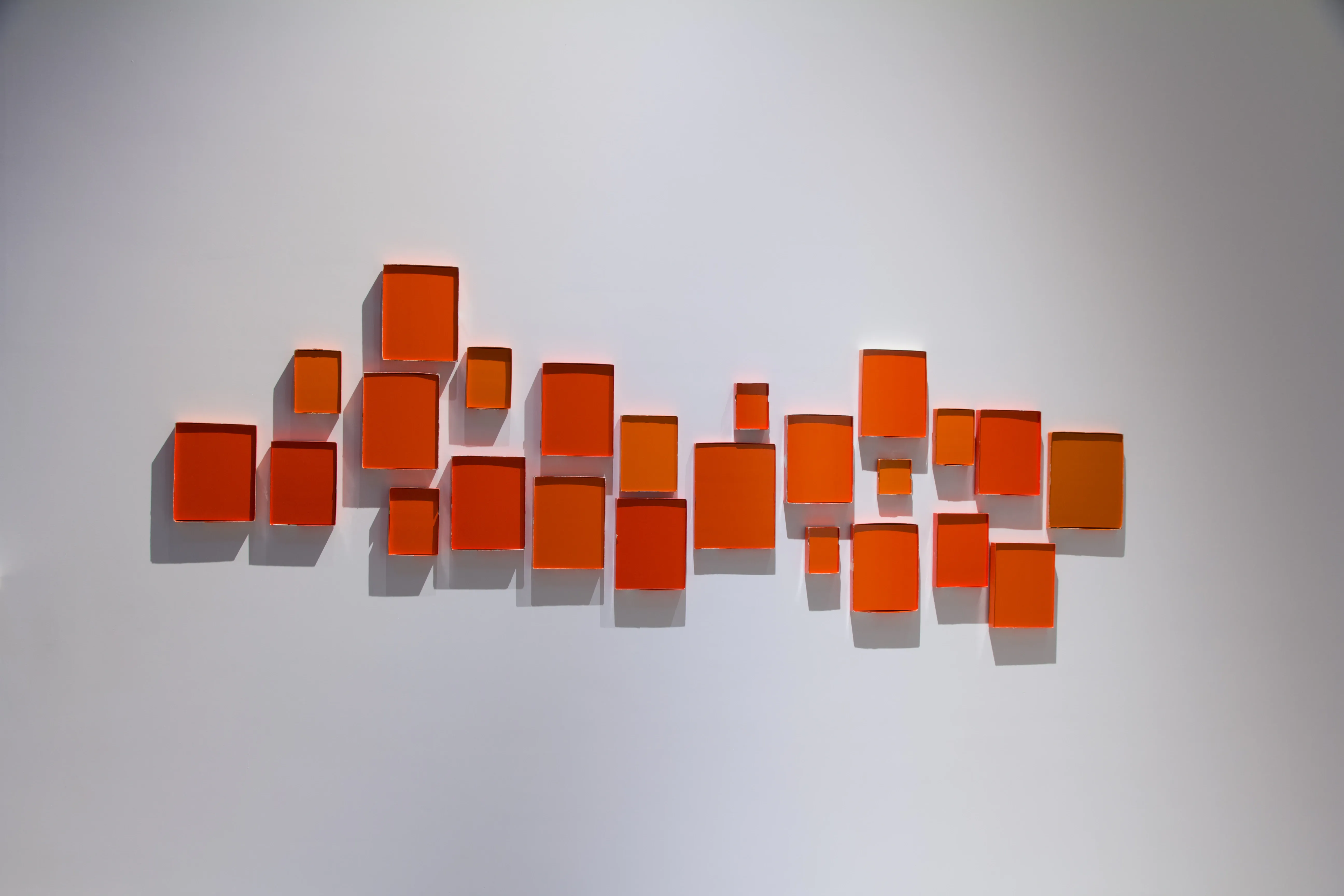

Shaun Waugh ΔE2000 1.1, 2014, 24 Agfa boxes with mounted solid colour inkjet photographs. Photo / Bryan James. Image courtesy of the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth.

Rather smartly, Bartley and Company in Wellington has brought together an exhibition to accompany Emanations of some of the New Zealand and Australian artists featured. For those not yet able to make it to New Plymouth, like me, it’s an exquisite treat.

Shaun Waugh is with Japanese artist Shimpei Takeda the youngest artist in the Emanations book by a fair few years. And the diverse potential of what a cameraless photograph can achieve is exemplified by the contrasting approaches of these two artists.

After the release of radioactive material following the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan, Takeda collected contaminated soil samples and left them on photosensitive film for a month. The result is a “blizzard” of marks showing radioactive emissions from the soil. Indeed, Takeda’s action recalls an 1896 experiment recounted by Batchen which accidentally demonstrated that uranium emitted radiation.

Waugh meanwhile provides a clever, witty meditation on the tension between analogue and digital technology, through pushing the concept of the readymade.

Arranged salon style in both Govett Brewster and Bartley shows are a set of old nostalgically familiar box lids for photographic paper. These frame inkjet prints of the same single plane of colour as the boxes. Look at the way the weathered edge of these boxes makes the group chatter together as a chorus.

I say the same, but the colours have been created by taking spectrophotometer readings (a kind of light reading) from the boxes they are within, with each box of slightly varying hue. Photoshop is then employed to approximate the colours. Each work is in this way distinctive from each other, and the photograph distinct from its physical source.

The most effective of the two works from reproduction looks to be that at the Govett Brewster, all orangey-red based on the Agfa boxes that house them. The Bartley work, meanwhile is a medley of Agfa orange, Kodak yellow, Ilford white and other brand colours.

The works are like cheeky little memorial open coffins for the loss felt by generations today of their physical prints and dark rooms. Yet they’re far more amusingly complex. Arguably the most abstract photographs possible, Waugh provides meditation on the way we try to recreate the real digitally, as if it's impervious to change. We’re poked into remembering that the originals were never exact. Boxes varied in tone from place to place in their manufacture, and ever since have been fading at different paces in reaction to their exposure to light. In Waugh’s absurd turn these boxes are cameraless photographs themselves.

Batchen’s book provides a fascinating account of developments in science at the turn of the 20th century in the use of cameraless photography to uncover the inner life of things. Joyce Campbell’s work at Bartley and Company and the Govett Brewster, like Takeda’s, recalls early scientific experiments in making the invisible visible.

For Campbell’s poetically floral and fluid-flooded work, micro-organic material was collected in swabs from the surfaces of plants and soil in Los Angeles. Then cultures were grown and photographic imprints made. These quiet works speak of the complex tension between nature and culture, and the latent fertility that remains in polluted landscapes.

Waterways, seaweeds and galactic systems are evoked through abstract weaves of faint blotches, dots and lines. I’m reminded of the abstract language of the painter Kim Pieters - that what is most natural can seem most alien to us. The photographic paper becomes a petri dish for our conversation with nature at a microscopic scale.

Nicely paired with Campbell are recent photograms by Anne Noble inside the beehive, continuing her technologically-playful series getting close to bees. There is the sense of a glowing rub up against the dark energy of the hive – the generation of an awesome heat. The field of vision becoming a burnt haze of abstraction in which the mass wings of bees beat up against the glass

The remaining work in the Bartley show is no less varied.

While Campbell is currently representing New Zealand at Sydney Biennale but rarely shows in Wellington, there are also here two Australian artists of note. Anne Ferran’s wedding gown photograms are well known. At Bartley a life-size gown flows down a wall on midnight blue-like paper, curling elegantly at its base. Pearly like a delicate pastel drawing, Ferran’s dress has an evocative flowing magical materiality. Another work that speaks of the power of this analogue medium to represent the real in charged new ways, it's a symbol of the lightness of innocence, the white arms of the dress cross like a strident symbol of protest.

Danica Chappell’s combination of tin-type and aluminium on timber providee gorgeously sharp collage abstractions that beguile with their textures, colours and reflections of light. Evoking the hard-edged geometric abstractive play of the early 20th century, these works also speak animatedly to the new community of history in Emanations.

Printed Emanations

Installation, Emananations at Govett Brewser Gallery. From left to right: Gavin Hipkins, The coil, 1998, silver gelatin photographs - Lucinday Eva-May, Unity in light #6, 2012, C-type print - Lucinday Eva-May, Unity in light #9, 2012, C-type print. Photo / Bryan James. Image courtesy of the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth.

Emanations the publication sensibly places its focus on a big suite of full photographic plates. In this way it emphasises their physical materiality and treats work of such varied sources equally. Like an old photo box of looseleaf images itself. There are 144 colour reproductions, preceded by Batchen’s very readable essay that works chronologically, with an elegant minimum of fuss, from the first to last plate.

This book is publishedwith an international market in mind. It roundly shirks being an exhibition catalogue. The fact that it accompanies the exhibition is only mentioned in the acknowledgements, and it presents a different set of works and artists to the exhibition. Unlike the exhibition, it doesn’t give New Zealand artists any additional privileges in presence. This is refreshing. Our artists are considered on their own merits.

This sees the New Zealand likes of Anne Noble, Paul Hartigan, Gavin Hipkins and Andrew Beck make the exhibition, but not the cut for the book. The most notable of those omissions for me is Beck, whose installations utilising cameraless photography are amongst the most distinctive works of art being made in New Zealand at the moment.

Batchen’s book is notable for its directness and simplicity – almost echoing its subject. Yet, while it’s refreshing to not have to wade through the usual introduction, foreword and credits up front, or superfluous title pages, there are a few annoying absences: an index by which to locate the artists, and a biography of Batchen himself.

Emanations strength as a history is that isn’t an existing history in the traditional sense at all. By embracing the artistic and scientific multiplicity of an underappreciated medium it avoids known, singular authorial readings of art history.

Instead, like a process of refraction it opens art history up anew to its physical contact with the world. Shining through it different angles of light.

- Contemporary Cameraless Photography, Bartley and Company Art, Wellington, until 11 June 2016

- Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph, Govett Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth, until 14 August 2016