Staying Conscious

Written by

A crisis – be it personal, national or global - has been defined as a time of intense difficulty or danger. Or a sequence of events through which the trend of all future events is determined; a turning point. There may be at this time that which has become a well-used phrase: “a moment of truth”. This can be symbolic. This week French president Emmanuel Macron called his handshake with Donald Trump on the 25 May as “not innocent” but such a moment.

But that’s politics. Generally, true recognition of truth leads to a consciousness about a crisis that you didn’t have before, and your own responsibility within it. We live with an environmental crisis or crises, but the level of our consciousness of this varies. It is as Al Gore termed it regarding climate change for his 2007 film “an inconvenient truth”.

Artists play a powerful bridging role between disciplines and value systems, and between our consciousness, the truth and ways we might face the future, as well as look back.

Two exhibitions right now in their directness of intent signal the urgency of our environmental situation. This Time of Useful Consciousness – Political Ecology Now, a group exhibition at the Dowse, takes the first part of its title from an expression of the moments between being deprived of oxygen and passing out. It’s also the title of a 2015 book by Ralph Chapman published by Bridget Williams Books, which has the subtitle ‘Acting Urgently on Climate Change’. Bartley and Company Art open, as I write, a group exhibition In the Anthropocene, the title meaning the current geological age in which human activity is the dominant influence on our climate and environment.

The Dowse exhibition’s ambit is broad, too broad. It’s a seriously impressive show full of significant new work, but its widened ambit from a more directed climate change focus doesn’t help. Political ecology (“the relationships between political, economic and social factors with environmental issues,” say the Dowse) is a big area to wade into.

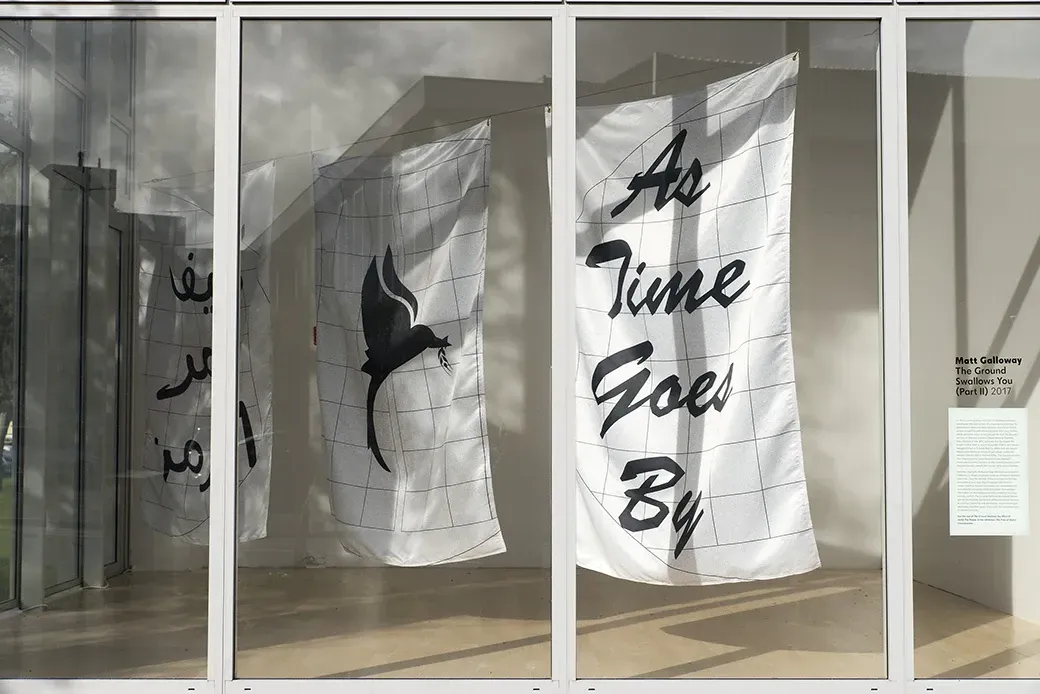

Two significant projects in the exhibition stick out in this regard. Matt Galloway’s ‘The Ground Swallows You (Part 2)’ - part one was at Blue Oyster Gallery Dunedin last year - was inspired by seeing a container ship of phosphate fertiliser enter Otago Harbour. Galloway traced it back to its point of origin in the Western Sahara, a disputed territory where the United Nations has raised significant human rights issues. Galloway visited refugee camps arising from the conflicts with Morocco in Algeria in late 2016 as part of the ARTifarati 2016: International Art and Human Rights Meeting of Western Sahara.

Key to the project is this graphic designer, publisher and artist’s freely distributed newsprint publication that provides accounts from direct personal experience. In a strong exploration of new graphic forms, it is complemented by a series of flag or camp-like banners with which to contemplate the relationship between peace and time, and a cluster of flagpole like aluminium rods, upon which are pierced, falling rippling towards the ground, various documents relating to human rights and sovereignty issues. Not even flying at half-mast, what are our flags worth if they don’t come with awareness of our responsibilities?

The project is strong in raising the need for personal consciousness of the human rights responsibilities that come alongside our gains from global capitalism. The project’s main thrust isn’t our relationship to our environment.

The visual lynchpin of the exhibition is Richard Frater’s ‘Stop Shell (Oyster Version)’, an oyster filtering water in the centre of the gallery. It raises awareness of how our greed and negligence conflict with corporate environmental responsibility (the Deepwater Horizon Disaster in the Gulf of Mexico).

Looking back to look forward

We cannot talk about our environment in Aotearoa without considering the values we have suppressed. Bridget Rewiti’s ‘I Thought I Would Have Climbed More Mountains by Now’ (first shown at Enjoy gallery) - well paired visually and conceptually with a John Pascoe photograph - is a strong reclamation by a woman and Maori of climbing and the view of our great Alpine landscape through a conquering Pakeha male lens.

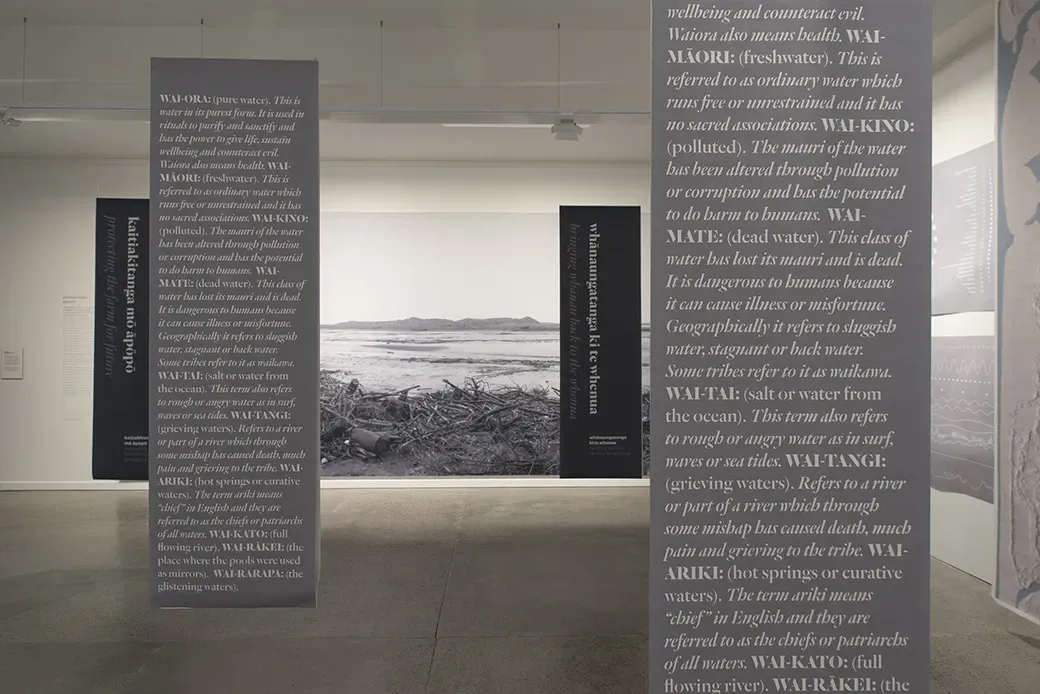

Far more on point though is the impressive museological display provided by the Kei Uta Collective with their project ‘Whakatairangitia rere ki uta, rere ki tai (Proclaim it to the land, proclaim it to the sea)’. The collective bring together science and art with a mātauranga Māori perspective, finding new strategies for dealing with the threats of sea level rise on the coastal Maori community of Kuku and Waikawa in the Horowhenua. Here the Ohau River was diverted in 1972 to allow dairy farmland to be developed, benefiting the Ngati Tukorehe tribe’s farm but causing environmental issues they have been working to put back in balance.

Given its own space this is a rich effective installation, within which the collective spatially explore how they might combine design, scientific and art elements in exploring new perspectives on a piece of land that stands for Aotearoa’s extensive depleted coastal wetlands. At its heart a series of banners outline the Maori multi-faceted terms for types of water. Interesting displays based on masters’ theses explore the potentials (with a look to the past) of the the flax industry, water care and new designs for kainga (villages), responding to sea level rise.

At the entrance to the installation Huhana Smith potently exhibits a series of small models of the local dairy buildings placed under Victorian bell jars. It’s not far from Kuku Beach to the preserved nature reserve of Lake Papaitonga, established by Walter Buller, who likely exhibited the now extinct Huia in such jars. The installation however is strategically looking forward: three lightboxes offer coastal maps for the future under the headings ‘protect’ ‘adapt’ and ‘retreat’.

Which format

The question that runs through my head taking in the entire exhibition are the best formats for the gallery to effectively explore the messages but also open up creative space for the viewer. Exploration of this is one of the exhibition’s really great strengths. But in pushing the boundaries it also exposes the public gallery’s limitations, or the needs for exhibition design to itself adapt.

The Distance Plan, founded by Abby Cunnane and Amy Howden-Chapman, is an ongoing project that brings together artists, designers and writers to discuss climate change within art. With a library provided, a series of publications (available rather nicely online here) and a series of posters there’s a lot of reading - which the gallery doesn’t provide adequate comfortable reading space for.

Howden-Chapman’s ‘Have You Ever Felt Overwhelmed’ will probably elicit the response “yes”. Based on a series of interviews with European experts on climate change while she was artist in residence at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, the installation comprises of audio of the interviews and an image of the observatory where they were based, looking up out to the sky. It proves a difficult space in which to listen.

The rest of the exhibition is dominated by moving image, a media adept at combining different disciplinary approaches (and which Howden-Chapman has been a smart user of). You could argue that Howden-Chapman’s work above, or the entire ‘Whakatairangitia rere ki uta, rere ki tai’ installation might have been better brought together in single experimental documentary works, but is that the place of the gallery?

The moving image works in This Time are in length and format made for the gallery, but you still need to leave plenty of time to enjoy them (they deserve to be watched for their full 10-20 minute length).

Providing welcome audio-visual immersion Tim Wagg’s ‘Cold Storage’ is a big wall sized two-screen front and back camera hurtle around the interior and exterior of the high security facility provided by a private infrastructure company for New Zealand’s National Digital Heritage Archive.

With a captivating soundtrack of electronic whistles, crackle and bells - you can sorta dance to - with exploratory verve the camera shunts us at electrifying pace through the corridors of the facility, disorientating us with the half-human half-robotic speed of its engagement. It’s as if we might be racing to find some hidden key in a video game over which we have no control. We’re thrown up against the physical reality of not having control over our data management. Prowling the high security perimeter, taking in the details of the alarm, cooling and fire extinguisher systems, that the facility is in Trentham in the Hutt, also home to a prison and a military camp, takes on a sinister undertone.

Pacific Specific

This exhibition recognises that in New Zealand climate change is very much a Pacific issue. One which we could do much better to address. That’s brought home by the inclusion of Matavai Taulangau’s three channel ‘Untitled (Pruning)’. It follows close at hand behind Pacific Island workers skilfully at work with secateurs in pine plantations. The focus is on their usually unseen sculpting work, not the wider industry. The wall text links us to the rest of the show in noting that since 2008 forest removals have been faster than forest planting.

In another space are twinned works filmed in the Pacific by Angela Tiatia and Vea Mafile’o. They are linked on the central wall by a large projection of Tiatia’s performance work ‘Untitled (Holding On)’ in which the artist in bathing suit lies Christ-like on a slab of rock with the water lapping around her, until dark. Simple, but eloquent.

Tiatia’s ‘Tuvalu’ is a three screen work, using blank screens effectively throughout for punctuation. Filming the coastal streets and shoreline as water floods in, the disturbing is counterpointed by golden light infused scenes of the idyllic, undercutting the Romantic image. It’s not subtle but its poignant - witness film of kids surfing on old fridge doors.

Over two screens Vea Mafile’o in Tonga and her family home of the Ha’apai island group provides the closest to a more traditional documentary approach. She effectively balances interviews which provide a close personal experience of changes brought on by sea level rise, earthquake events and sand removal, with camera shots which brings us close to an into the water. This a place where the interviewees tell us that children no longer play on the beach because of the dangers.

Right now in the Hutt where the Dowse is based, the springs celebrated for their fresh water are closed to public drawing due to concerns about e-coli contamination. Flooding and the effects of the recent earthquakes are causing great concerns. It may strike some as odd that the immediate issues around climate change in the Hutt don’t feature then in the exhibition. But it doesn’t need to. This Time of Useful Consciousness does well in placing the complexity of perspectives into a wider regional, Pacific and global place.