The Long View

Written by

In 1963 a group of Wairarapa citizens plotted to purchase a work by my favourite British modernist sculptor Barbara Hepworth. They did so in support of a proposed arts centre. They wanted to set a high standard.

A campaign was launched to persuade the people of Masterton that the work was a good investment and would stimulate public interest in the arts. A fundraising campaign raised half the funds, with the Maunsell family, owner of local firm Hansells providing the rest.

Today that centre is Aratoi, the Wairarapa Museum of Art and History. It is one of many outstanding regional art museums that we, collectively, have invested in since the 1960s. Like a few others it has an outstanding permanent collection of locally, nationally and internationally significant artwork, built up over decades through purchase, bequest and gifts.

What a different juncture we find ourselves at now. Gone, naturally is the day when we relied on the cred of a British modernist to kickstart an art collection. (Although with the commission of a major work by Martin Creed for the Christchurch Art Gallery in 2015 some perhaps might beg to differ.) Indeed, recently the Aratoi Foundation has successfully secured 90% of the funds needed to bring a substantial new work by New Zealand sculptor Neil Dawson (who spent childhood years in Masterton) to the middle of a rather drab roundabout. The work is an impressive 10-metre high double helix structure suspended five metres above the ground. A Boosted campaign late last year failed to raise a remaining $14,000 from the public – make of this what you will in regards to crowdfunding public art.

But what of the public gallery? Do we feel confident that if a similar public fundraising campaign was run today towards a small outstanding work for a regional institution the funding would be found? Or does our public art have to comprise of giant state lighthouses or abstract airborne whirling dervishes?

In October came the news that, in the face of substantial funding cuts Aratoi Director Alice Hutchinson – one of only two fulltime staff - was stepping down. At present an interim director Susanna Shadbolt is in place, and the museum has been forced to close Mondays to keep costs down.

You sense these aren’t easy stakeholder times for many of our regional galleries. After a relatively glorious period of collection development and then new building development over recent decades there may - without appreciable visitor increases - be an air of ‘so now what?’. You could smell the unease in a recent Stuff article grumbling about the “Ninety-three per cent of New Zealand’s council owned art gathering dust”. It didn’t suggest much of an appetite for the purchase of new work for permanent collections.

And yet if galleries aren’t collecting contemporary work, what kind of appreciation of art are we cultivating? Does art increasingly come to be seen as something for the walls of the moneyed few? How well is art’s relevance being couched?

Offering food for this thought: there’s an excellent pair of collection exhibitions at Aratoi currently. One is of little seen landscapes from the Aratoi collection (The Long View, until 19 March), the other recent work from two private collection groups (Waisculpt and Et Alia: Two Collections Six Years, until 24 February).

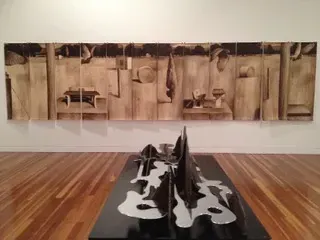

In The Long View you’ll find the Hepworth sculpture in its own small room behind perspex, gleaming like the giant fins and tail of a Humpback Whale jumping out of the sea off the Kaikoura coast. Nearby is another Aratoi piece de resistance, Robin White’s 12 panelled ‘Summer Grass’. A glorious, hazy, airy golden-light poetic response to the region’s relationship to a Featherston patch of land that was once a Japanese prisoner of war camp and site of an ‘incident’ in 1943 in which 49 were killed. ‘Summer Grass’ powerfully reverberates in light and movement the complexity of our cultural relationship to our past.

In front of it is a magnetic early work by sculptor Chris Booth. It is far different from the work Booth would go on to make a career out of. It reminds me that his great mentor was Barbara Hepworth in St Ives herself. Booth’s work counterpoints a dark vertical mountain silhouette with a gleaming horizontal pooling river, flowing like silver mercury. He cuttingly encapsulates in three dimensions the landscape of the Wairarapa, as if it were a knife carving through the collective consciousness.

And indeed, the Wairarapa is territory where the land dominates in a way that makes landscape art seem, like in Canterbury a core concern. A beautiful John Weeks work here (part of a swag of work Helen Clark gifted to museums nationally when they were returned from MFAT back in 2001) could be from any landscape in New Zealand. But here at Aratoi it feels emphatically this one.

Colin McCahon, Buck Nin, Marilyn Webb, Toss Woollaston, Bill Sutton - next to great more overlooked Wellington artists like Susan Skerman and Juliet Peter. It’s a terrific collection. Yet what is noticeable is an absence of contemporary work. I may be wrong but ‘Summer Gras’s in 1981 is about the end of it. I very much suspect that regional galleries can no longer afford to collect like they used to, or lack the resources and spirit to call out to private collectors to bequest and donate. I’d love to be corrected. Otherwise, like our published written art history we’re in danger of losing the public except in spats beyond Colin McCahon.

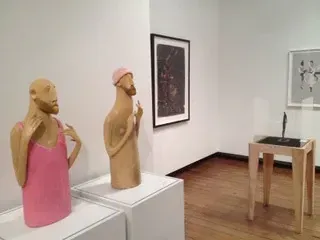

Meanwhile, in the Wesley Wing of Aratoi is a fabulous bringing together of great wee work from some of our finest contemporary artists from the joint collections of two art buying groups. Were it able to be seen for longer and wider.

It’s really rather rare to see publicly paired artists as seemingly disparate as Andrew Beck and Michael Hight, yet such a pairing really works. Through strong curation and collectors’ love the show sings beautifully: an ode to the fresh inventiveness of New Zealand’s contemporary artists. There’s even a work by Ray Handon that feels like the stainless steel child of Hepworth’s copper and bronze. You won’t see shows this diverse and people-sized at Te Papa or Auckland Art Gallery.

As the title of the Aratoi collection show states, public galleries need to collect for ‘the long view’. Local authorities, trusts and the public themselves need to recognise that a culture that doesn’t collect its contemporary art is leaving future generations bereft of some significant reference points in how we saw ourselves and the world around us. Not to mention the opportunity to invest - like a Hepworth or McCahon - in work of immense future civic value.