The Matariki Box

Written by

Courtesy of The Dominion Post

Mark Amery discusses the work of two artists who weave together past and present, Diane Prince and Matthew McIntyre Wilson.

Celebration of the Maori New Year, Matariki has had exponential adoption by public institutions in recent years. It's well on its way to a more widespread public adoption as a significant event in the calendar. Courtesy of The Dominion Post

Mark Amery discusses the work of two artists who weave together past and present, Diane Prince and Matthew McIntyre Wilson.

Celebration of the Maori New Year, Matariki has had exponential adoption by public institutions in recent years. It's well on its way to a more widespread public adoption as a significant event in the calendar.Matariki refers to the group of stars also known as Pleiades that are visible in the night sky at this time of the year. It was celebrated long before the arrival of Pakeha as a time of new beginnings, as well as remembrance for those things past. It's a time of preparing the ground for the future and for the sharing of knowledge. As such it provides an easy fit for a focus on art.

This Matariki in Wellington sees a number of exhibitions by Maori artists - although it turns out for many of the art dealers this programming convergence is a neat coincidence. At Janne Land is what is these days a rare exhibition of recent work (2003-2005) from that great contemporary granddaddy Ralph Hotere. At Peter McLeavey is painter Darryn George, and around the corner at Bowen Galleries Diane Prince. Opening on Saturday out at Solander in Lyall Bay is Rising Stars - Nga Whetu Whitinga, an exhibition of the work of artists from Toi Whakataa the Maori Printers Collective. The title is a reference to the seven sister stars of Matariki, and indeed gleaming at City Gallery's Michael Hirschfeld Gallery is Seven Sisters, an exhibition of the work of Matthew McIntyre Wilson.

I do sense a danger however of Matariki becoming a convenient banner under which to box in art labelled as Maori, rather than to recognise that maoritanga - a culture, a unique way of seeing the world - is part of the bedrock of what constitutes contemporary life in New Zealand. That Matariki the event becomes a convenient public nodding acquiescence to tradition, once a year masking, and letting out our tension around outstanding issues concerning Maori sovereignty.

That is implicit in the title of Diane Prince's exhibition, Kia Hiwa Ra Alert. Be watchful. In her exhibition notes Prince comments that, "the silencing of our people through the agencies of colonisation has been a continual feature of my work". Prince also notes that she formed a trust with Iwa Holmes of Pipitea Marae in 1993 to reintroduce Matariki celebrations.

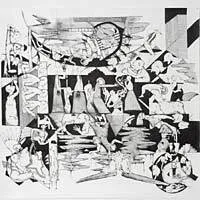

Prince's new series of works in indian ink crackle with complexity. They don't just celebrate and venerate, they dissect and erupt. Her drawings form pulsating organic wholes which see language in the midst of the battle of dying and being reborn, of being colonised and overcoming - like a viral attack in a Petri dish.

These works are an extraordinary conglomeration of fractured shape-shifting elements, where the lessons of Maori weaving and carving are evident in the way the tumult is held together in a weave as bewildering an Escher drawing. The beautiful gymnastic study of the figure and its fluid choreography from one focussed dramatic moment and artistic style to another piles on evocations of early Renaissance frescos and the muscular drawings of Michelangelo, the surreal monstrous gardens of Hieronymus Bosch and Francis Bacon, and even the grand elegant decorative swoop of an E.Mervyn Taylor depiction of Maori legend. I'm also reminded of the work of Bill Hammond, both in the spatial complexities of the work (all snakes and ladders in and out and across the plane) but also that birdland of figures, where muscular dancer-like gymnast spirits represent the emotional twists of our sense of being.

Like the carvings of the wharenui they make Maori oratory physical as a serpentine pattern of figurative line. Formed primarily from the profiles of heads and upper torsos, mouths open to allow the spirits of the past to pour out, or alternately to be gagged by words poured by others. Stitches and tacks in their heads indicate an institutional lobotomisation. It is as if each work is an operating table of cultural incisions - history unfolded as a map full of creases that have cut across people's connection to their past and sense of themselves (previous work has dealt visually and conceptually with the colonial fragmentation of land).

Prince suggests words build worlds, but the pointed finger is also shown as powerful as the rifle. There are allusions aplenty to the colonising power of church, court and government, but the work is also refreshingly unpreachy. It expresses the complexity of what makes us who we are. Anger is channelled here into something as beautiful as it is horrific. This is a powerful portrait of the people of this land in a battle between defiance and despair, suffering attempts to be boxed in as words are stuffed into their mouths.

Also impressive is Matthew McIntyre Wilson's exhibition. Glistening and chattering to each other jewel-like in low light, in a beautifully curated show by Abby Curnane, Wilson's kete and other forms made out of copper and silver provide a meditation on the object as both functional and decorative. A substantial look at Wilson's practise and how it has come of age recently, it also shows the depth of his interest in pattern and its complexity, paying homage to a range of cultural sources. Included are meticulous preparatory drawings which highlight how even in pencil each pattern is a pulsating architecture.

While it's noted that each pattern comes with its own important story, it's interesting and slightly disturbing that these stories aren't provided. It's as if either Wilson is unsure of his right to tell those stories, or as objects created for purchase and gallery exhibition he wants them to be vessels for new ones. What is to be enjoyed is the cultural freedom of the work, and how Wilson owns the complexity of his own makeup. "Being put into this category as a Maori artist is something I haven't fully worked out - ," he comments in an accompanying interview. "I have come to this Maori art 'place' from a Pakeha world."

Kia Hiwa Ra Alert, Diane Prince, Bowen Galleries, until 5 July

Seven Stars Matthew McIntyre Wilson Michael Hirschfeld Gallery, until 30 July

Image: Diane Prince, Politics of memory, 1645 x 1415, ink on paper, 2008

Photo credit: Stephen A'Court

25/06/08