Creative New Zealand’s plan to support Pacific arts

Creative New Zealand (CNZ) is developing a Pacific Arts Strategy for the first time, a policy to guide their support for Pacific arts over the next five years. To kick off this process, they hosted a Pacific Arts Summit at Te Papa Tongarewa in March, the first gathering of its kind since 2010, bringing together artists, art organisations, and members of the Arts Council (which governs CNZ) to discuss what the strategy should consider.

Over the the two-day summit, emerging and established artists working across various disciplines added their voices into the discussion of what “Pacific arts” is and how CNZ could best support this. People working curation, management, and business side of art also contributed their valued perspective, and members of the Arts Council voiced their appreciation for everyone contributing to the talanoa.

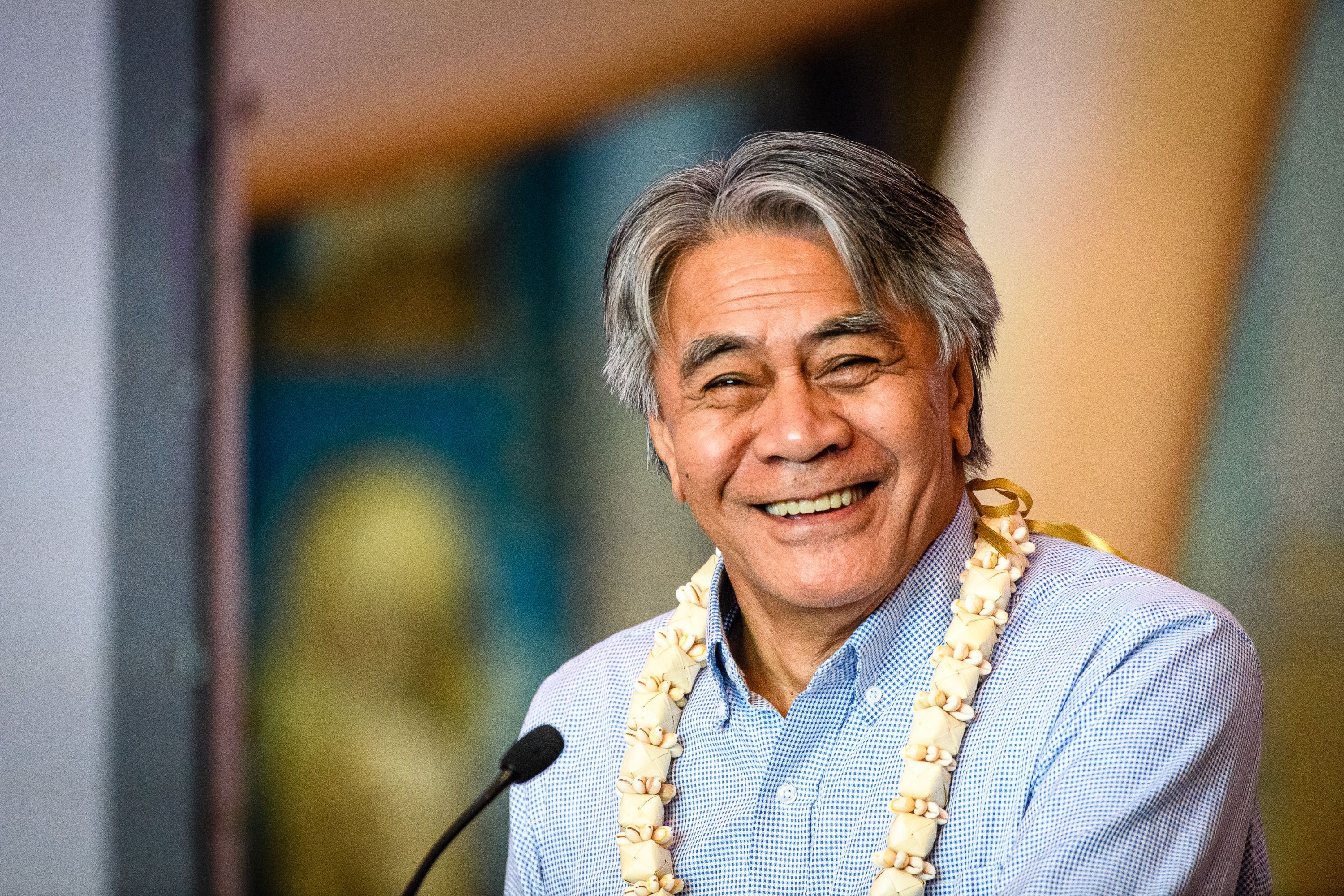

Samoan actor and director Nathaniel Lees was the summit facilitator and emphasised the importance of the gathering as the first step in CNZ’s process. In putting together the artists for the panel sessions and leading the talanoa groups, there was sure to be conflicting opinions abound, which is crucial for a discussion such as this.

What began as a simple question — How can Creative New Zealand best support Pacific Arts? — led to broader questions; about the imagined Pacific community/ies, about CNZ’s role within the arts industry, and the role we believe art plays in our society. Who do we include as “Pacific arts” practitioners? As funding providers, can CNZ contribute to creating an arts ecology independent of government funding? Does the label of “Pacific arts” liberate or debelitate practioners?

Big questions to mull over just two days.

For some people (maybe more than some), the distrust ran deeper than just CNZ. Polynesian Panther, musician, and all-round badass Tigilau Ness cited Makerita Urale, writer and director and arts advisor to CNZ (and the driving force behind the summit), as the only part of the bureaucracy that he trusts. Everyone else, particularly Pākehā men, who he said historically and systemically worked against Pacific communities, is yet to gain that trust. He voiced his distrust to the CNZ representatives who were present, and they responded, acknowledging government’s historic biases and that they were using this opportunity to listen to the ways they can build more positive relationships.

Nathaniel credited Makerita as a the driving force behind the summit, and tells me that CNZ really is trying to change. The summit is one way to draw on knowledge they don’t have, he said, it is a place for debate and discussion, and, crucially, helping CNZ develop an understanding of how complex our communities are.

So, here are a few ideas I took away from the summit about what our community of Pacific artists and CNZ can collectively focus on to take us closer to our vision of a strong, connected Pacific arts scene:

1. We need to define who we are and what we do

First things first, what counts as “Pacific art”? Is it art made by Pacific people? Is it art made by anyone who takes inspiration from Pacific cultures? This framing is foundational to how CNZ funds projects and practitioners.

First things first, what counts as “Pacific art”?

Many artists at the summit felt that defining Pacific art creates a box for something that should be fluid, ever growing, ever changing. Polyfest is an iconic festival with high schools competing in cultural performances and people fill the ASB Showgrounds every year. Using this as a benchmark for Pacific art however would exclude many work by Pacific artists.

In the opening panel session, the Matua Panel, Lemi Ponifasio stressed that “Art isn't about the production of stuff, we're constructing societies we want to live in, cultures we want.” Scholar and poet Karlo Mila and summit panel speaker noted that artists push the boundaries of what the imagined “us” is. Art then, is a way of thinking through cultural boundaries, imagining worlds and situations where what is real is not what we are currently experiencing. Pre-empting what “Pacific art” looks like works fundamentally against this idea.

On the other hand, the category is necessary when used as affirmative action, for artists who feel they work within a sector that has systematically excluded and disadvantaged their communities.

Gary Silipa, visual artist and gallery director proposed the idea of framing the strategy to support “Pacific artists” rather than “Pacific art”, putting the focus on the artist’s vision, rather than casting a poorly-imagined genre onto artists.

2. Don’t forget your roots

Heritage artists work in preserving and passing on knowledge down the generations through art practices that communities have inherited, such as carving, weaving, and tapa making. Curator Kolokesa Mahina-Tuai described heritage art as the “roots of Pacific arts” and these artists especially need recognition and support. For Kolokesa, “there is no distinction between art, culture, and life”. The things we make have social function in our lives. It holds history, it provides a space for people to gather, share stories, share burdens, laugh.

Director of the Pacifica Arts Centre, Jarcinda Stowers-Ama, shares that “the word ‘art’ is a little strange. For us, it’s a way of life, it’s a way of breathing. It’s the way we are.” For many heritage artists, passing cultural knowledge and building communities are key and the tangible ways of doing this culminates in what can be labeled as art.

However, Jarcinda pointed out that, “many of our heritage artists don’t know about the money and grants available, they’re entitled to some of that.” Supporting heritage artists and art communities benefits Pacific artists across the board. She went on to say that with zero funding, the Pacifica Mamas would still find a tree to sit under, make tīvaevae and tell stories. Art is culture.

CNZ invited iTaukei (indigenous Fijian) heritage artists to present and discuss their work at the summit, and the urgency of this work in keeping language and cultural knowledge alive.

3. We need to build a bridge from New Zealand to the Pacific

Pacific artists who live and work in the diaspora (such as here in New Zealand), use art as a way to think though history their place in the world. The region of the Pacific is an audience that needs to be a part of the conversation. For interdisciplinary artist Yuki Kihara, this requires bridging the wide cultural gap between those living in New Zealand and the Pacific.

The pinnacle of success is often framed as making work that translates for Pākehā audiences, and international recognition is measured by oversees Pākehā. The Pacific as a region is not valued by major funding bodies for things like residencies, film festivals, and other international collaboration. Bringing heritage and contemporary artists into the same room needs to happen.

CNZ need to go more to foster international networks and support because there is an appetite and market for art from Aotearoa, but they also need to turn to the Pacific as just as legitimate (even more so) as Europe or America.

4. We need to create a community where artists and art organisation pool their skills and resources

We follow each other’s work and make networks, but in terms of providing support for each other’s practices, we need an accessible place to ask for help, to share expertise, career advice, and practical things like asking if anyone has an amp for an upcoming exhibition launch.

Artists are often expected to play two roles: an exceptional practitioner artist, and a business that manages their finances and resources. The opaque funding avenues don’t make things easier. Acquiring funding provides more obstacles than necessary. Pacific artists are talented and hard workers, but information about the creative industry and infrastructure is not always available. Artists cannot be experts about how to navigate the public and private market while there are no established bodies providing guidance.

Perhaps this is not something we can ask CNZ to create, but something Pacific artists, and indeed all artists, need to build themselves.

------

What’s next?

FAFSWAG founder and Tanu Gago summarised his thoughts about the summit in two words: action and accountability. Turning to CNZ, the ones who brought us all together, Tanu told them that we need to see their commitment in tangible ways, quick. “You like to put us together, hear us talk. But we need you to do something.”

Though the summit is over, the conversation is far from it. CNZ will be accepting online submissions in April from those who couldn’t make it, as well as those who were present and have more to add. These submissions will help to inform the final strategy.