Cultivating a healthy working environment: Ngā Rangatahi Toa 8 years later

The Big Idea interviewed Sarah Longbottom in 2010 about Ngā Rangatahi Toa, a then newly established organisation that aimed to provide access to the arts for rangatahi who have been excluded from mainstream education and labelled “at-risk”, as a way to provide them with new pathways of understanding themselves and the world around them.

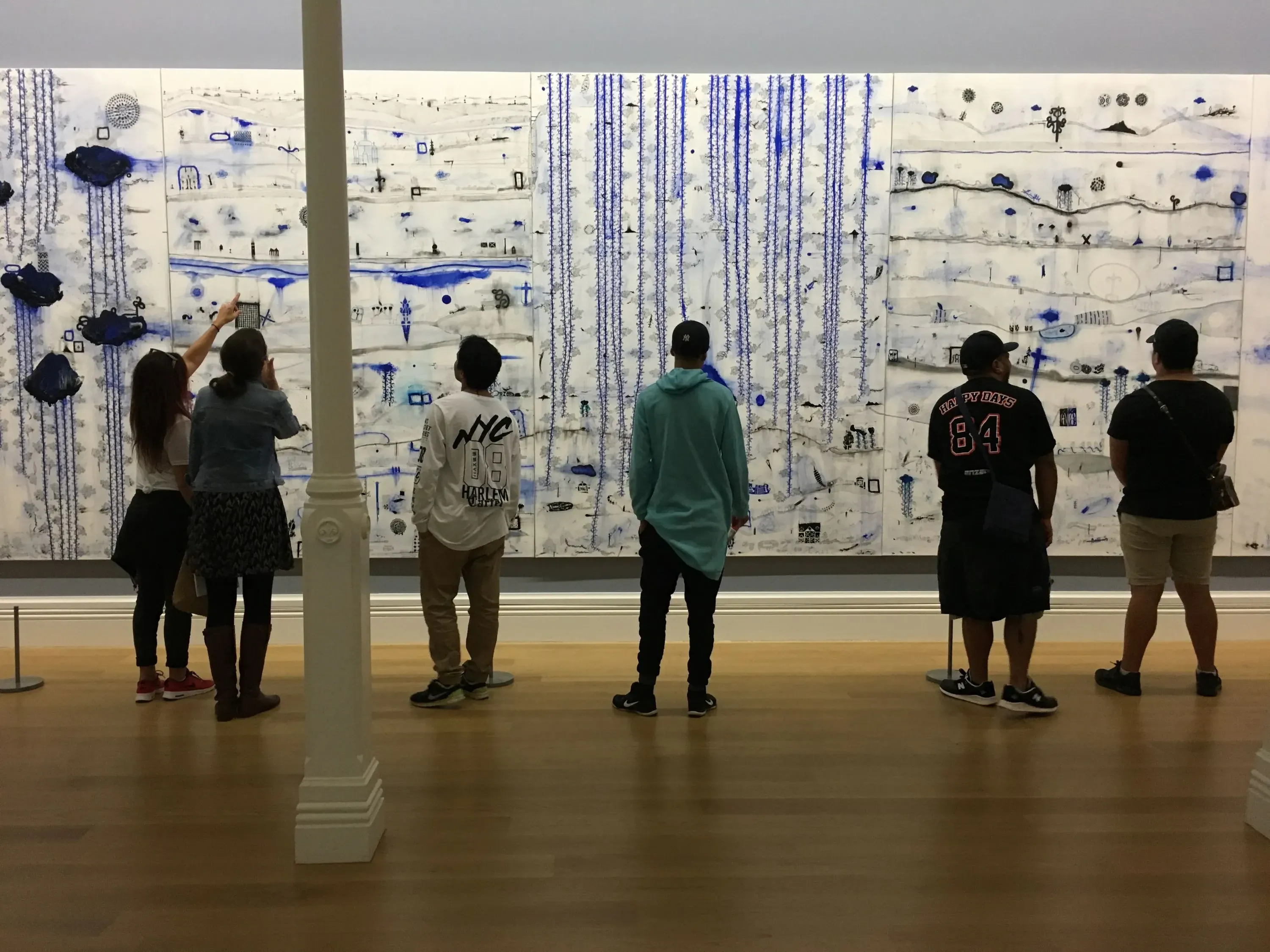

Since then, the focus has moved from arts access and being a way in for these rangatahi to the arts as a possible career pathway, and has turned to prioritise the power of story. The clear focus is now empowering rangatahi to own their story and take control of the narrative of what it means to be Māori, to be young, to be who they are and to live in some of the most under-served neighbourhoods in our country. These stories are too often shaped by the hands of those in established power; a dominant narrarive is created that is removed from the nuanced reality of the lives of these young people.

For such fundamental changes to be made successfully, Sarah and her evolving team went through the (oftentimes painful, but always necessary) process of making mistakes, learning from them, and taking critique from others.

Sarah reflected on the evolution from being a ‘startup’ to becoming a more stable, established, and self-reflective organisation. The unbridled “startup mentality” had eventually cultivated a culture of sacrifice and overwork, measuring self-worth and the marker of progress by the levels of personal exhaustion—the more tired, the better.

Ngā Rangatahi Toa have moved from this over-exertion survival mode to one that placed human relationship at the core and upheld a compassionate environment as the crucial setting for the most productive, transformative and fulfilling work to take place in. Sarah now places more importance on making sure the working environment is conducive to the practicing self-care, holding space for staff to go deep within themselves in order to become better practitioners.

The better position staff arrived at within themselves, and with each other, the better relationship they were able to nurture with rangatahi and whānau.

Sarah goes on to say that an important part of knowing herself was bring her personal history and context to the forefront of her mind, reflecting deeply on what it means to be Pākehā. Being part of the dominant ethnic group, Sarah and other Pākehā are hardly required to reflect on their cultural identity and history and how this has shaped this country.

Sarah notes that all Pākehā need to hold at their core a willingness, as well as a sense of urgency, to learn from te Ao Māori and seek wisdom from Māori who are open to sharing their knowledge about this land, about human connection; to be immersed in a worldview that she sees as the way forward for New Zealand, Aotearoa.

Sarah talks about the beauty and importance of true creative communication and collaboration, something she learned from friend Che Maxwell, leader and tutor for Ngāti Rangiwewehi kapa haka group. From Che, she has come to understand that behind the stunning performances that are seen on the stage of Te Matatini Festival, is a deep connection on a spiritual plane that goes far beyond the ‘known’ and is cultivated in a space of real collaboration and patience. The wairua of kapa haka lies not just in the outward expression, but in the interconnectedness and tikanga behind it. This is the way that Ngā Rangatahi Toa seeks to emulate.

When asked what have been the strongest forces of support during this time, Sarah said undoubtedly it would be this whenua: “If I’m ever in doubt about the direction that Ngā Rangatahi Toa should take, I just go and observe nature. I understand our connection with nature, that we are part of nature, and that as soon as we start to do that ego-driven, exhaustion-as-a-badge-of-honour stuff, we’re working at odds with nature, at odds with our true selves.”

This sense of listening to nature also taught Sarah how to accept and move through rough patches: “Part of learning from the whenua is observing nature and understanding that the proccesses of death and decay is a part of life. As soon as you try and actively avoid that, you’re going in the wrong direction. ”

Sarah was frank about the reality of working with rangatahi. “There’s always ups and downs with our kids because they’re human. There’s a balance—everything good, everything bad, nothing lasts. We do amazing work with a young person and then shit would fall apart in some area. That’s the ebb and flow of life.” One thing that is always present at Ngā Rangatahi Toa, no matter what the circumstances, is laughter and humour. These rangatahi, whose lives could so easily be (and are) painted as simply tragic, or minimised to an inspirational turned-my-life-around story, are really a mix of both tradegy and triumph. There are structural oppressions but also so much joy in the friendships they build and the incredible learnings they’re able to cultivate from theur sometimes dire situations.

The big idea that Sarah is moving through 2018 with is that the only wisdom you have is in knowing you know nothing. She intends to sit comfortably in the space of uncertainty or incomplete knowledge and not freak out. To be patient in not knowing, and move slowly, as nature does.

To read more about the work Ngā Rangatahi Toa do, you can read about it here.