The film school advantage

Written by

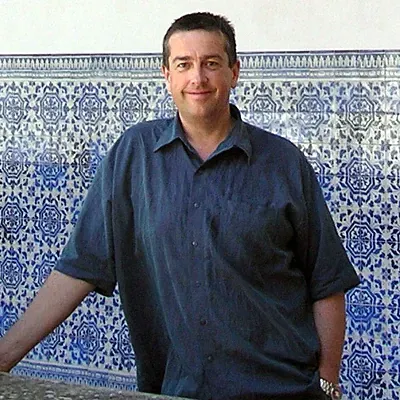

From making the first NZ short to win at Cannes Film Festival, to teaching masters level script writing at AUT, Andrew Bancroft is in a league of his own.

In this interview with Ande Schurr, he shares his perspective on today’s film schools, building a better industry and getting the best from an actor and script.

* * *

There are two important factors to getting the best head-start in the film industry.

The first is a personal drive to make it work. If you are self-employed, you have come to terms with this reality. You are your own boss, you make your own contacts and you develop the film making crafts at your own pace. In essence, there is nothing that anyone can do to change your drive. You either want to jump out of bed in the morning or you don’t.

The second factor is education. For those who have friends or family already in the film industry, you can use them as mentors and circumvent formalised education entirely. However if your confidence is lacking, your skills are too coarse, or your just need time and opportunity to prepare yourself properly, then you should consider film school.

This interview with Andrew Bancroft - the first New Zealander to have his short film Planet Man (1995) win at Cannes Film Festival and now the head of AUT Masters of Creative Writing for Screenwriters - is important because it makes a solid case for allowing time to properly develop your craft.

As co-supervisor for one of the New Zealand Film Commission’s short film POD schemes, he saw three of their five short films get into Cannes Film Festival. When asked how they did this, he said that they simply spent longer developing the scripts.

This simplicity is what Andrew is all about. He knows what to focus on and what is superfluous.

How do you deal with the young (or old!) student who wants to make a career as a film director and script writer yet is frightened by the abounding perception that there are lean years ahead for anyone daring to enter the screen sector?

It depends on whether the students are from NZ or overseas. I describe the current reality of our screen sector as best I can. More of an issue for them is their motive to become a ‘writer’ and/or ‘director’. At film school, they often find the reality of these roles is far more challenging than they imagined. Some realize that skills they have learned are applicable to other industries.

The more pressing question for anyone drawn to directing is whether you want to be a director, or to direct. The former is about role anxiety - how others see you and how you want to see yourself. Whereas directing is actually doing it - telling a story in pictures.

It is also understandable, for example, why writers and actors might want to become directors. To make your work powerful you need to make it truthful - and to make the work truthful, you must find something personally, emotionally real for you in it... Yet the actor or writer never knows what the director will do with their work – so becoming a director seems to be a way of controlling the outcome. At film school, students realise that directing is a different skill, a different art form, and one who is good at acting or writing may be not suited at all to directing.

Ultimately, in my experience the ones who have a burning to tell their story – as writers or directors or - just go ahead anyway.

What should the focus and responsibility be for today's film schools to prevent, or better manage, an abundance of graduates, or do you not see this as a problem?

My focus is on scriptwriting and directing for cinema, and NZ film schools need to develop that talent because they are the future of the big screen. After film school, increased support would help them to build a career by getting their work in front of audiences. Overseas, I have seen that a large, productive, networked community of practitioners is the way to grow an industry and an audience.

If you have had the opportunity to visit other film schools around NZ or internationally, what observations did you make about good practices?

I have often taught in-between my screen projects because I am fascinated with the question of how do you teach filmmaking? I have done stints at film schools around NZ, at universities and techs, the NZ Writers Guild, etc, and with support from the Film Commission I’ve also trained with various filmmakers overseas. Over twenty years I feel like I’ve developed a keen sense of what works and what doesn’t.

In a nutshell, I feel one needs an integrated curriculum based on storytelling at an introductory level. “Film” is really a compendium of six different disciplines – photography, design, music/sound, writing, acting, and editing. Six completely different art forms which need to be combined and orchestrated to become a compelling story for an audience. To teach this means you need a clear and unifying understanding of what a screen drama is – how script structure, photographic elements, design choices, and editing rhythms create and affect the relationship between audience and character, which in the end is what matters to the audience the most.

There are systematic programmes for training actors, and have been for a century, and for still photography, for composing music, and so on. But it’s rare to find an integrated system for teaching storytelling on the screen. Instead, things are often taught as separate disciplines – camera over here, sound over there. In my experience, that’s not effective. Instead, everything needs to be based on storytelling – to teach sound recording, lighting or colour correction as standalone skills, as if they exist apart from their role in helping tell a story to an audience, is a falsehood. All an audience cares about is story, and so should we filmmakers.

You've had a trail-blazing writing and directing career. Your short-film Planet Man, became the first NZ short film to win at the Cannes Film Festival in 1996 and your TV Movie, Signatures: Nga Tohu, which you co-wrote with Hone Kouka but directed yourself, took out the Best Director, Best Actor, Best Actress and Best Supporting Actor at the NZ Film & Television Awards in 2000. Now, as an executive producer and educator, do you miss expressing your creativity or do you find that you get the same sense of satisfaction in your new roles?

I have often taught while between creative projects. Partly this is because I find teaching shares a lot in common with directing and creative producing. I try to bring the best out in the people I work with, I try to create an atmosphere of creativity and courage, but also of being truthful, and telling stories which matter. Students come from different countries, cultures, ages and worldviews, and this can be energizing, eye-opening, humbling.

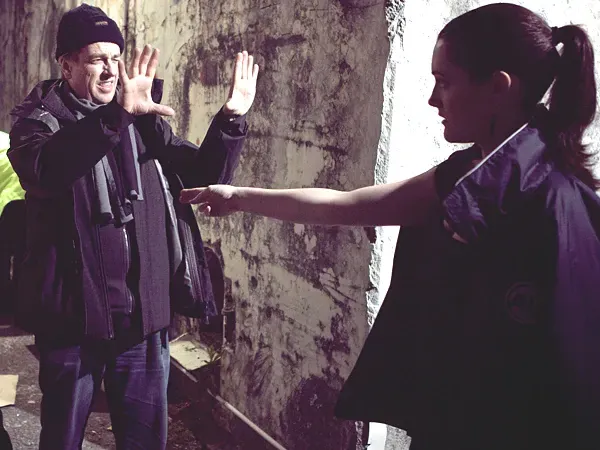

How do you direct actors and get the performances you desire?

There are specific techniques that I have found work for me, and for the actors I have worked with, and then there is also that personal understanding of psychology that a director must develop.

We are a small industry in which there is more TV made than cinema, so actors often gain their screen experience in fast-turnaround TV drama, and I find my job is to help them put that to one aside. Instead of ‘acting a role’, they need to be. To do, not to perform.

It fascinates me how TV drama does everyday situations very well, and in everyday life we sort of act out a version of ourselves – we perform – and therefore acting on TV suits performing, so that we watch “the actor acting a role”. The challenge of cinema, due to size of the big screen but also to pace, is that it does not permit falsehood. You can’t pretend.

So how do you, as an actor, appear real? You have to be real. And directing is an interesting job when it is helping someone be real.

As head of the AUT Masters of Creative Writing for Screenwriters programme, you are responsible for developing eight feature film scripts with your students. Where is the line that you draw in terms of contributing creatively to their work?

I have worked as a script editor in Aus/NZ and use a similar approach: my role in the development of a script is figuring out which question to ask when. It’s up to the writer to provide answers. The right question can open doors and illuminate options that they might not have considered before. At the same time, I and the other advisors try to create a supportive, discursive environment among the writers themselves and suggestions tend to fly thick and fast. This is the first, dedicated one-year intensive in Auckland (taking screenplays from concept to second draft) and some very motivated people have signed up. It’s a real hothouse.

What are your personal views of the current film environment in NZ in terms of developing talent, funding and creating a thriving eco-system for filmmakers at all levels?

The opportunities are there. In addition, I feel there are two key areas where more training/support could be useful.

One is – when I was co-supervising a POD scheme for the NZFC, I was surprised that the need for a long period of script development was news to many aspiring filmmakers. Afterwards, we often got asked, how did we get three of our five completed shorts into the Cannes Film Festival? My reply was we simply spent longer getting the scripts right. So any initiative (or film course) that emphasizes this is a good investment in my view.

The second issue is - while TV directors often have backgrounds in theatre, film directors seem less aware of not just how to direct actors, but of the power and creative potential within actors. Actors are magic.